Damnedest eye I have ever seen

The figure represents the eye of the silver spiny fish, Diretmus argenteus. Elizabeth Pennisi reports in Science magazine that this fish lives in the very deep ocean, where there is no ambient light from the sun. Unlike many other creatures, such as blind cave fish, that lose their sight when deprived of light, these fish have evolved an eye that detects the faint glow of bioluminescence.

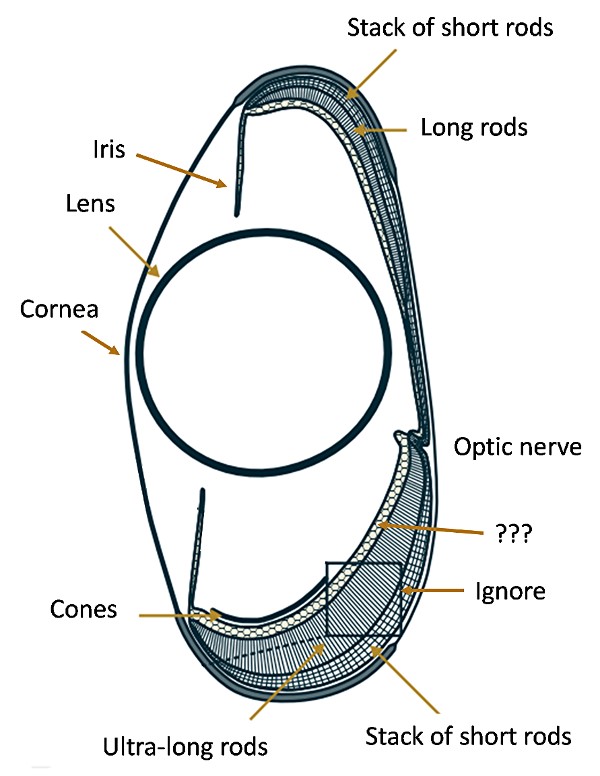

And what an eye it is! It consists of a cornea, a ball lens, an iris that is probably fixed and functions only as an aperture stop, and a variety of rods that apparently can distinguish color. Layers of rods are piled on top of each other. In the upper part of the drawing, the long rods are 95 μm long, and the short rods in the stack are each 15 μm long. The lower part of the drawing shows a layer of ultra-long rods 525 μm long and a stack of short rods 27.5 μm long. The rods contain different photopigments, or opsins, and span the range of bioluminescence wavelengths. Presumably the lengths of the rods also have something to do with color sensitivity. There is also a layer of cones, but I will hazard the guess that they are nonfunctional, since cones are generally used in bright, or photopic, illumination. It is unusual that the rods, which are used in dim, or scotopic, illumination have evolved to distinguish colors. I do not know what the honeycombed area represents, but it is probably various retinal layers that are not light-sensitive.

The optics of the eye is also interesting. The bulk of the receptors appear in the upper and lower parts of the picture, not along what you might think of as the axis, so the fish sees primarily above and below. I will hazard another guess, that the index of refraction of the liquid inside the eye is close to that of water, so the cornea is weak, and most of the power is due to the ball lens. I do not know whether the lens actually projects an image or merely acts as a condenser; see the Appendix.

The original paper is Vision using multiple distinct rod opsins in deep-sea fishes, by Zuzana Musilova and 17 others. The paper is concerned primarily with the evolution of the opsins, not the structure of the eye.

Appendix. The focal length f’ of a ball lens is given by

f’ = nD/(4(n – 1)),

where D is the diameter of the lens and n is the index of refraction. f’ is (in this case) measured from the center of the sphere. Very roughly, if the drawing is at all to scale, the focal length would have to be about equal to the diameter in order to project an image onto the receptors at the very top or the very bottom of the drawing. If the index of refraction of the lens is 1.8, then we use n = 1.8/1.33, because the lens is surrounded by water, and we find that the focal length is roughly equal to the diameter of the lens. If that is so, then the system operates at a relative aperture of f/1. The lens in the human eye has an index of refraction around 1.4, and most common solids and liquids display indexes below 1.6, so an index of refraction of 1.8 seems high to me. On the other hand, if the cornea has power, as possibly evidenced by the location of the aperture stop, then the index of the lens may be lower than 1.8.