How scientists resolve conflicting theories: Origins of Leishmania found

People have very different opinions about the world. I don’t like melted cheese, but you may love the creamy goodness. Similar scientists develop contrasting hypotheses; however, they base these hypotheses on evidence. How do scientists develop different hypotheses? One scientist may see a pattern in one phenomena and try to apply it to another one to possibly explain why it happens. If two scientists tried to apply different patterns they observed to the same problem, they would end up with different opinions. A reason specific to phylogenetics that scientists have different hypotheses is because of morphology. Morphology is the study of form and structure of organisms. Before DNA became widely used, the only way to figure out how species were related was to look at their morphology and the fossil record. From there, similar looking species would be put in the same groups. One could hypothesize that bats and birds are closely related because they both can fly, but another may hypothesize that they are distantly related because bats nurse their babies with milk and birds do not. Molecular phylogenetics is one way that scientists can have more evidence to understand relationships among species because DNA is the hereditary material and not subjective to different opinions like morphology. An example of the utilization of DNA is the resolution of the debate between scientists about where the parasites that cause leishmaniasis originated.

Leishmaniasis is a disease that affects approximately 12 million people in more than 90 countries. Many other vertebrates besides humans can contract the disease, including dogs and rodents. Infection is caused by Leishmania, a genus of eukaryotic parasites. To move between hosts, Leishmania infects an insect vector, sand flies, when they suck the blood of another vertebrate host, the Leishmania infects the new host and their life cycle is complete. At least 12 species infect humans and cause three main types of leishmaniasis: cutaneous, visceral, and mucosal. The type of leishmaniasis that is contracted depends on the species which caused the infection. (Read more about Leishmaniasis here.)

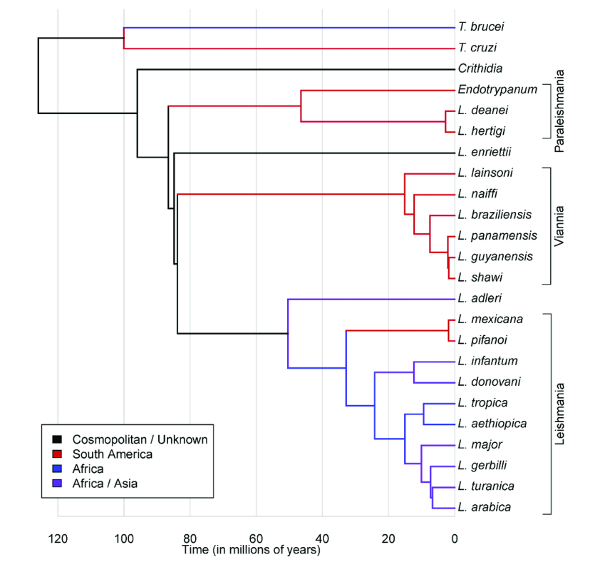

Currently, scientists agree that living species of the genus Leishmania are grouped mainly by where they exist in the world. These groups of species are called subgenera. The Leishmania subgenus includes all the species in the Old World (Africa, Europe, Asia) and one species in the New World (the Americas). The Viannia subgenus contains the rest of the species in the New World. Species of Leishmania that infect Old World reptiles have their own subgenus called Sauroleishmania.

How did Leishmania get to be all over the world and where did they come from? This is where scientists disagree. There are three conflicting hypotheses that each propose a different origin and way Leishmania became dispersed throughout the world.

The first hypothesis is the Palearctic hypothesis, where Leishmaniasis is believed to have originated in lizards about 145 to 66 million years ago (mya). Leishmania then migrated over land bridges through their vertebrate hosts and vectors to both the nearctic (North America all the way up to arctic Canada and Greenland) and the neotropics (South and Central America). According to this hypothesis, the subgenus Sauroleishmania would be sister to all other species. In other words, all other species would be more closely related to each other than any of them are to Sauroleishmania. It’s like Sauroleishmania is your cousin. You are more closely related to your siblings than you are to your cousin, just like the Leishmania and Viannia subgenera are more closely related to each other than to Sauroleishmania.

The next hypothesis is the Neotropic Origin hypothesis, which suggests New World species are ancestral to Old World ones. Contrary to the Palearctic hypothesis, Sauroleishmania, the reptile-infecting forms, would be derived from mammalian infecting forms, rather than being ancestral to them. In this case, Sauroleishmania would be a sibling of Leishmania’s instead of the cousin. One problem is that there would have to have been separate migrations of the parasites across the vast ocean to another continent.

The last hypothesis, Multiple Origins, suggests that Leishmania diverged into two lineages on Gondwana, a super continent that contained Africa, South America, Australia, India, Arabia, Antarctica, and the Balkans. One lineage was the ancestor of Leishmania, Viannia, and Sauroleishmania. The other lineage was the ancestors of all other species, which infect New World mammals. When Gondwana broke apart, the Viannia subgenus ancestors were moved to present day South America and separated from the Leishmania and Sauroleishmania subgenera in present day Africa. One group of the Leishmania group in the Old World possibly moved from Africa through Eurasia to North America when conditions were favorable for the vectors, sand flies, to survive.

So, who’s right and where did Leishmania really come from? Harkins et al sequenced the genomes of 12 species of Leishmania to determine that. They found that the subgenus Leishmania is most closely related to the Sauroleishmania subgenus than any other group. Together, Leishmania and Sauroleishmania subgenera are more closely related to Viannia than other species, a subgenus called Paraleishmania, and the outgroup of a different genus, Endotrypanum. (You can see more of their trees here.) With this data, each of the three hypotheses can be supported or rejected. The first hypothesis, Palearctic, is rejected because Sauroleishmania is not sister to all Leishmania species but most closely related to the Leishmania subgenus. The Neotropic hypothesis can also be rejected because the estimated dates of the split in subgenera do not match the dates calculated in the experiment. The Neotropic hypothesis also suggested an origin of 36-46 mya for all Leishmania species while the experiment suggested an origin of 90-140 mya. The only hypothesis that was not rejected was the last hypothesis, Multiple Origins, because it most closely fit the data that Viannia and Leishmania subgenera separated about 100 mya due to the separation of South America from Africa and that Paraleishmania was the first separation to occur.

Harkins et al propose a modification and expansion of the Multiple Origins hypothesis to a new hypothesis they call Supercontinent. On Gondwana, the ancestor of Leishmania emerges and when Gondwana begins to separate, the subgenus Paraleishmania is split from the rest of the genus, around 90-100 mya. The split between Viannia and Leishmania occurred around 90 mya when Africa became isolated from South America. These ideas and dates are consistent with the estimated divergence dates from the data. There would only be one migration, from the Old World to the New, around 30 mya over the Beringia land bridge when temperatures were warm enough for sand fly, and therefor Leishmania, survival.

This is an example of how scientists can resolve debates and conflicts over different hypotheses: through experimentation and the resulting data. It also shows that science never stands still. Our knowledge of the world is continually expanding.

This series is supported by NSF Grant #DBI-1356548 to RA Cartwright.