We may be more hardwired than we thought

Fascinating article by Rhitu Chatterjee in Science this past week. I am not a specialist in physiological optics, but I have always understood that you cannot give sight to someone who is blind from birth and is older than, perhaps, a teenager. According to Chatterjee’s article, most ophthalmologists understood the same thing. It is not true.

Chatterjee describes a project to perform cataract operations on people who are congenitally blind. Some of these are teenagers or young adults, and they learn to see – not as well as you and I, possibly because part of their visual cortex has been used for touch or hearing, but they learn to see. In consequence, a neuroscientist, Pawan Sinha, launched Project Prakash as a humanitarian effort to give sight to people who have blindness that would be preventable in the developed nations.

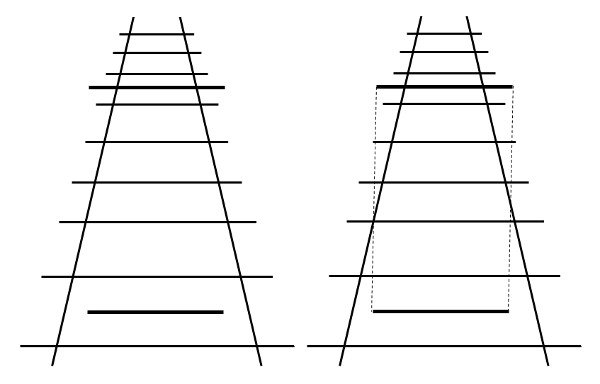

What interested me more, in a way, was that newly sighted people fell for precisely the same optical illusions that normally sighted people fall for. For example, the two bars across the railroad tracks in Figure 1, the Ponzo illusion, are the same length, as you can verify with a ruler. The dashed lines on the right side of Figure 1 are parallel and show that the two bars are the same length – except that the illusion persists, and the dashed lines do not look parallel.

Probably most readers are familiar with the Ponzo illusion. The usual explanation is that we learn over time to recognize 2-dimensional drawings of 3-dimensional objects, and we think that the upper bar is farther away than the lower bar and so must be longer.

Amazingly, 9 newly sighted children fell for the Ponzo illusion.

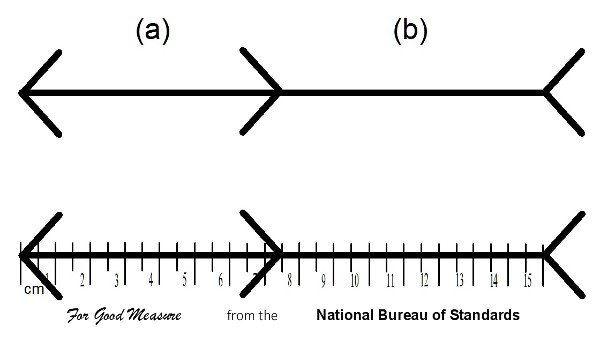

Likewise, Figure 2 shows the Müller-Lyer illusion. Here, (a) the line segment with the arrows pointing out always looks shorter than (b) that with the arrows pointing in. The illusion persists, even when we provide a ruler to show that the lines are the same length. (See also here for a slightly different view of the Müller-Lyer illusion.)

Once again, the 9 newly sighted children fell for the illusion.

No one Chatterjee spoke to has a good explanation, but it seems that we must be hardwired to perceive and interpret much more than is commonly thought.