Evolutionary educational resources in the U.S.

The majority of U.S. medical schools do not require evolutionary biology as a prerequisite for acceptance and do not offer courses dedicated to the subject. But as we talked about last time, adopting an evolutionary perspective on medical issues can potentially give new insights into disease treatment, prevention, and diagnosis. Where do we and should we begin to teach this kind of thinking? What resources are available to teachers and students to learn about evolution and its application to modern day problems?

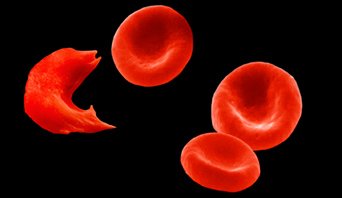

Evolutionary training can help doctors look at diseases in a different light (Nesse et al, 2006). Take, for instance, sickle cell anemia: carriers of the sickle cell trait, a disease which is highly prevalent in tropical regions, are resistant to malaria, likely as a result of natural selection. This knowledge is helpful in developing ways to prevent malaria and perhaps similar evolutionary links between other diseases or infections and protective traits exist, but examining this hypothesis requires a thorough understanding of evolution and population genetics. Based on examples like this proponents of evolutionary medicine believe evolutionary biology should be considered a core subject for medical students, side by side with anatomy, physiology, biochemistry, and embryology, and that medical license exams should include questions about evolutionary biology.

But while most medical schools do not offer much in the way of evolutionary education, there are some resources available for K-12 students and teachers as well as college undergraduates and graduates. One example is the BEACON Center for the Study of Evolution in Action at Michigan State, an interdisciplinary research team working on applying evolutionary principles to a wide range of problems in fields such as medicine, computer science, ecology, and engineering. Along with research, BEACON is focused on evolution outreach and education: researchers are conducting studies to see if integrating undergraduate cellular and molecular biology courses with evolution improves evolutionary understanding. The center also organizes K-12 summer programs, activities for K-12 teachers, and undergraduate and graduate-level courses.

While BEACON is enjoying great success, the NESCent (National Evolutionary Synthesis) Center, a center in North Carolina promoting multidisciplinary evolutionary research, will be closing this year after a decade of operation. Like BEACON, NEScent was also active in public outreach and education, organizing events like Darwin Day for K-12 students and training workshops for graduate students and teachers. But a new center is opening in the wake of NESCent: the Triangle Center for Evolutionary Medicine (TriCEM), which will focus on the partnership of evolutionary biology with human and veterinary medicine.

We’ve made the case for why an evolutionary understanding can improve research in medicine. But if we want to shift the paradigm of medical thought to one that emphasizes evolutionary biology, we need to reevaluate how we teach evolution from the earliest levels of education through medical school.

This series is supported by NSF Grant #DBI-1356548 to RA Cartwright.