Phylogenomic Fallacies

This is the fourth in a series of articles for the general public focused on understanding how species are related and how genomic data is used in research. Today, we talk about some common fallacies in phylogenomics.

Where do humans fit on the evolutionary tree of life? This is an important topic in evolutionary biology. A lot of people believe humans are the most important and highly-evolved organisms, but in reality, all modern species are equally evolved. Our natural tendency to assume that humans are evolutionarily superior has led to a few misconceptions about phylogenetic trees.

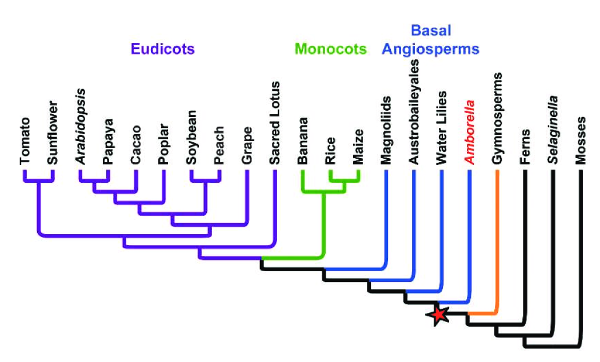

To understand the first misconception, let’s look at a phylogenetic tree of plants (from “The Amborella Genome and the Evolution of Flowering Plants”). Eudicots and monocots are two classes of flowering plants, or angiosperms, and the plants in black are non-flowering plants. The term “basal” refers to the base of a phylogenetic tree, and a basal group is a species that branches closer to that base. The authors chose to label the angiosperms that are not eudicots or monocots as “basal angiosperms.” But this label is arbitrary; all the angiosperms are equidistant from the common ancestor and thus equally evolved. We sometimes tend to give more weight to branches that contain the species of interest and call other branches basal, almost assigning them a lesser importance. In this case, the species of interest is plants that consist of many foods that humans eat; a species is often deemed more important as it relates to humans. But modern species are equally evolved from a root common ancestor regardless of when their branch diverged from the common ancestor. To avoid confusion, it might be best to eliminate the “basal” term altogether.

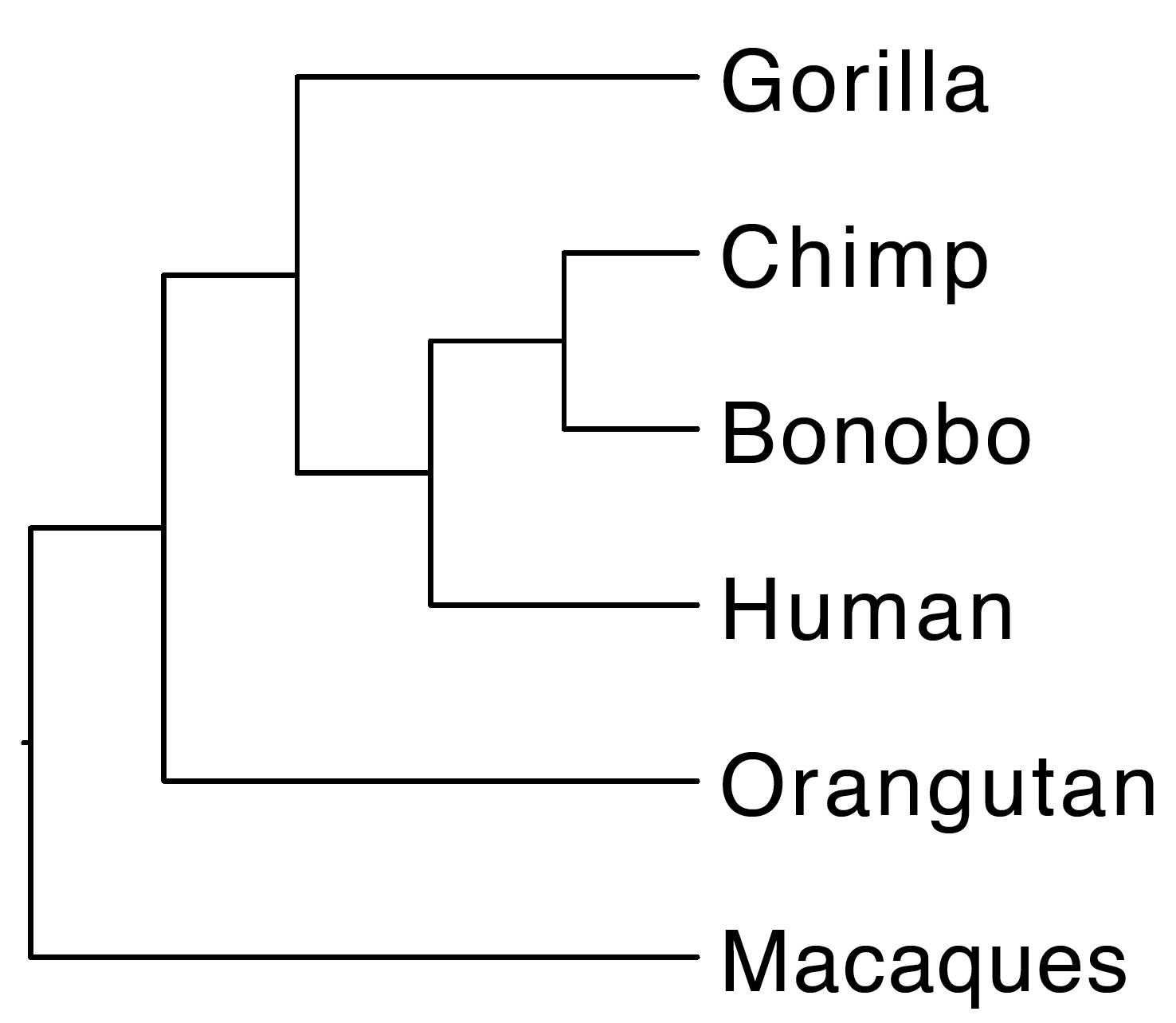

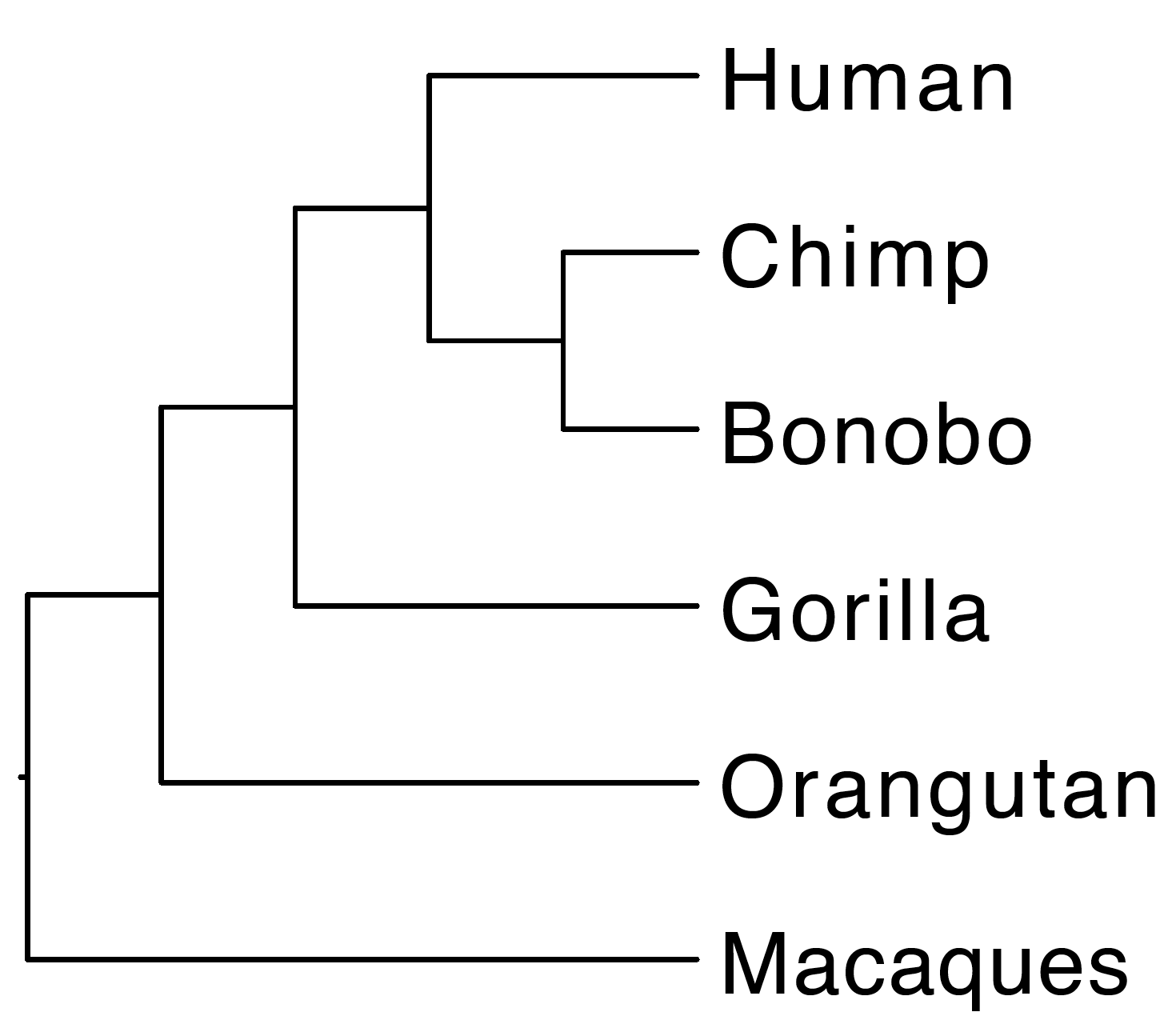

This type of thinking also leads us to place humans at the end of phylogenetic trees. However, this placement is arbitrary and trees can be drawn in many equivalent ways. For example, compare a tree of primates with the branches rotated. The tree on the left, with humans at the top of the tree, is one you might see more often. But both of these trees are actually identical, and the relationships between species that can be inferred from the tree on the right is the same as the relationships in the tree on the left. Species at the tip of a tree are equidistant from the root common ancestor, so they can be considered evolutionarily equivalent.

Similarly, a common misconception is that humans evolved directly from monkeys. Monkeys, though, are modern species just like we are and have been evolving and changing over time. The common ancestor we share with monkeys may have looked much different than monkeys do now. This assumption that modern species represent an ancestral state of human evolution is what T. Ryan Gregory calls the platypus fallacy. Gregory uses the example that we can’t examine the traits of platypuses and think that humans at one point in their evolution possessed these same traits. We can no more infer the traits of human ancestor species from platypuses than platypuses can infer the traits of their ancestors from us.

Human-centered thinking is very prevalent in our society, affecting our laws, religions, and customs. While it probably influences all of us on a personal level, it can lead to false conclusions and misconceptions in science, like thinking that humans are the most highly evolved species. But all modern species are evolutionarily equivalent because they have been evolving for the same amount of time. Eliminating this fallacy will enable us to better understand the evolutionary process.

For more information on basal groups, check out: “Which side of the tree is more basal?, Krell, Frank et al. Systematic Entomology (2004).

This series is supported by NSF Grant #DBI-1356548 to RA Cartwright.