Accessible research: Natural selection reduced diversity on human Y chromosomes

We just had a paper published over at PLoS Genetics entitled, “Natural selection reduced diversity on human Y chromosomes.” But, as you may recall, it has been available on the arXiv for quite some time.

Others have already summarized the work (Razib Khan nails the punchline, and Ian Sample has a summary for the popular press).

Below are answers to many of the questions I received about this work.

How would you describe the importance of your findings?

|

| Human chromosomes by Paquete |

The human sex chromosomes, X and Y, used to be nearly identical, but now the Y has lost 90% of the genes it once shared with the Y, and some have speculated that the Y chromosome will disappear in less than five million years. We show that human Y chromosomes are much more similar to each other than expected. Previously, variance in male reproductive success (meaning some men fathering many children, and some men fathering few or none), was thought to explain this similarity, but we show that an additional force, natural selection, is needed to reduce diversity across Y chromosomes to the levels we observe.

Could you briefly explain how exactly you showed that variation on the Y chromosome is consistent with natural selection? What does this mean?

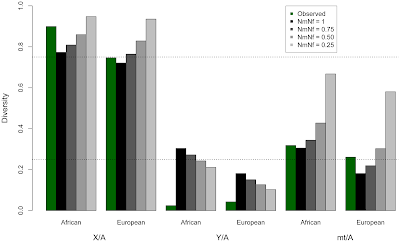

We first ran statistical models that let us alter the number of males and females that contributed their genomes (the non-sex chromosomes, chromosome X, chromosome Y, and mtDNA) to the next generation. We reduced the proportion of males passing on their genomes to the next generation in a series of experiments, but in doing so, the modeled estimates of variation in the genome did not match the observed levels of variation.

|

| Here none of the grey-scale bars match all of the green bars |

We next developed statistical models to estimate the number of sites affected by purifying selection on a set of hypothetical Y chromosomes, then tested which models were most likely to have acted in the past, given what the variation we observe across the genome today. Purifying selection removes, or purifies out, harmful mutations. It can also affect linked neutral sites. However, everything on the Y chromosome is linked together, so selection acting anywhere on the Y-specific portion of the Y chromosome will remove variation across the entire chromosome.

We found that, accounting for population-specific variation in male reproductive success (boxed results below), the number of sites predicted to be affected by purifying selection on the human Y chromosome fell in between the number of single-copy coding sites and the total number of sites in the ampliconic regions.

|

| Maximum likelihood estimates of chrY sites affected by purifying selection. |

This means that in addition to the single-copy coding genes on the Y chromosome, the highly repetitive, but still poorly understood, ampliconic regions are likely also affected by natural selection.

Purifying selection - that removes harmful mutations - acting on many sites of the Y chromosome, resulted in a population of Y chromosomes as similar to one another as the the Y chromosomes we observed in the real human data.

Were you surprised to find what you uncovered?

We were surprised to see how much of the Y chromosome is affected by selection. Here we show that at least some of the the highly repetitive ampliconic regions (so called because they are amplified in copy number) are acted on by selection. These regions are necessary for sperm formation and function, but are poorly studied because of how difficult it is to sequence them. Our results suggest that we need more investment into studying the most challenging parts of our genome.

What can you say about the function of the 27 genes located on the Y chromosome. What do you know about the ampliconic regions?

|

| Y-linked genes help sperm form and swim. |

Although not part of this study, I can say that the 27 genes on the Y chromosome can generally be divided into those that function in many tissues, and those that now primarily function in the testes. The ampliconic genes are only turned on in the testes. Both these groups appear to have major roles in sperm motility and function.

What can your research tell us about our ancestor’s history. How does it change the picture?

When we think about the population of our common ancestors, what this tells us is that, although there has certainly been variation in male reproductive success, and that this varies across populations, the genes on the Y chromosome continue to be preserved because they serve an important function. It also tells us that estimates of the time to the most recent common ancestor of the Y chromosome might be underestimates if purifying selection has been a constant force, reducing diversity on the Y chromosome.

|

| Portrait of Genghis Khan |

Certainly there is variation across human populations. In some populations, variation in male reproductive success will have a stronger impact. For example, I look forward to extending these results to see whether the Y chromosomes of Central Asian populations, with the genetic legacy of Genghis Khan, might show more of an effect of variance in male reproductive success.

What makes the sex chromosome history so fascinating for you?

Everything! I am amazed at how the X and Y used to be nearly identical, just like any of our non-sex-chromosomes, and yet today the Y has lost 90% of the ancestral gene content, and both X and Y have accumulated sex-specific elements. I want to understand why these chromosome became so different in some lineages but not others, how this process is shaped by population history, what unique role these chromosomes play in health, and where we can expect them to go in the future. See other posts on sex chromosomes in emus, spiny rats, and in the plant, Silene latifolia.

Can you give me some examples of mammals that already lost their Y chromosome?

The Okinawa spiny rat. However, it is unfair to say it completely lost its Y chromosome. What we think happened is that a few of the genes on the Y chromosome (or at least the sex-determining gene) jumped to a non-sex chromosome pair. In some Okinawa spiny rats, it was recently discovered that the degraded Y chromosome fused to a non-sex chromosome pair. This new location, although we haven’t identified it yet, will now evolve into the next sex chromosome pair.

In what ways do these results present a step forward in the debate on whether or not the Y chromosome is more or less dispensable?

Our findings suggest that natural selection is acting strongly on the human Y chromosome, and it is unlikely to disappear any time soon - you can call me on this in 5 million years if I’m wrong.

Why is there still so little coverage of the Y chromosome in genome sequencing?

It isn’t so much that there is so little coverage of the Y chromosome, but that most projects do not assemble the reads they have from the Y chromosome, and there’s a good reason for this - most of it is a mess! With the current technology, the length of pieces of DNA (usually 100-200 nucleotides) to look at from genome sequencing are too short to get a good handle on many of the highly repetitive regions of the Y chromosome. With new advances in technology, or with a lot of time and diligence using more involved techniques (such as single haplotype iterative mapping and sequencing, SHIMS), we will learn more about these difficult to study regions of the Y chromosome.

How do your findings fit into recent research in mice that only two genes on the Y chromosome are necessary to produce offspring? Even though the Y might not disappear it seems to be superfluous soon.

|

| MRI of human head |

The mouse Y chromosome work showed that by using twoY-specific genes, SRY, and Eif2S3Y, mice would develop with male characteristics and would produce immature sperm (it isn’t clear if they could develop fully functional sperm). In this case, I can say that the trajectory of the primate, specifically the human, Y chromosome and the mouse Y chromosome are very different. The similarity with humans is that SRY is also one of the main regulators of pathways that turn on testes formation, but a big difference is that the second gene, Eif2S3Y, is broken in humans. Furthermore, the mouse Y chromosome is pretty wimpy, in gene content, compared to the human Y. The human Y has retained many more genes from the ancestral mammalian sex chromosome, and many of these have been shown to function in sperm formation and motility, so it seems like it will be much for difficult for fertile, sperm-producing humans to develop without a Y chromosome. Furthermore, while many of the human Y-linked genes are involved in male-specific functions, there are several that are turned on in other tissues, such as the brain, and liver, so it seems unlikely there are more genes that are involved in form and function on the human Y than the mouse Y. That said, there are humans who have a single X chromosome and no partner X or Y (this is called Turner syndrome), suggesting that fertilization is a resilient process.

What do you think might be the most important aspect of your research? How can it be used in the future? What are your next steps?

One of the most important aspects will be understanding whether positive selection has also played a strong role in shaping human Y chromosome diversity. We did not have the power to detect a difference between purifying selection (which acts to remove harmful mutations) and positive selection (which acts to increase a beneficial mutation in frequency), but plan to look at this in the future as more Y chromosomes are sequenced.

Is there anything you might want to add or stress concerning your studies?

We find complementary roles between variance in male reproductive success, and selection, in shaping the pattern of variation on the human Y chromosomes. It will be fascinating to assess this in more human populations, to see how local environments have uniquely shaped the evolution of the Y chromosome.