A Very Darwinian Halloween

It’s Halloween, so it’s time for a roundup of the SCARIEST October stories in the evolution versus creationism wars!

Plants doing unnatural things to animals

More than a few works of horror and hyperventilating YouTube videos have been inspired by the Venus Flytrap (Dionaea muscipula), a plant with jaws and “teeth” that has a nasty habit of eating bugs that get too close after being lured in by red coloring and secreted nectar.

The actual plant isn’t very big, and the traps don’t get bigger than a quarter, but imagine what a bug would think, if bugs could think:

The Venus Flytrap: So inviting, yet so dangerous. Source: wikipedia.

Creationists like the Venus Flytrap too! In fact, decades before Michael Behe made the mousetrap and its “irreducible complexity” (IC) a thing, the traditional creationists were arguing that the Venus Flytrap trap was too complex to have evolved gradually, and that it must have been designed instead. I guess they thought God had an inordinate hatred of beetles.

The ID people sometimes venture into the Little Shop of Horrors, for example with this October 14 post on the Discovery Institute website, The Venus Flytrap, an Improbable Wonder that Baffled Darwin.

The Discovery Institute post, by the way, might well be authored by David Coppedge, the young-earth creationist who runs the website Creation-Evolution Headlines and who in 2012 lost a lawsuit against JPL, after a huge amount of drama and rhetoric from the DI. It rather fits his style – quote a new paper, refuse to do any due diligence to look to see if there has ever been any research at all on the evolution of the system in question, and declare victory. The main evidence against it being Coppedge is that it begins with “here in Seattle”, unless Coppedge has moved from LA to Seattle.

In any event, “dcoppedge” has definitely written lots of posts for the DI’s Evolution News and Views (although some of these are by other authors, perhaps indicating a shared account and/or Coppedge doing website work in addition to straight writing). I guess after his JPL loss, Coppedge has been working for the Discovery “we’re not creationists, we swear!” Institute. Strange that he’s not listed as an author anywhere on the DI website. Are they…SCARED? Accuracy of the connection between ID and creationism – the horror!

Anyway, you know who else likes Venus Flytraps? Why, evolutionists. Have a look at the logo for next year’s Evolution 2014 meeting in Raleigh, North Carolina:

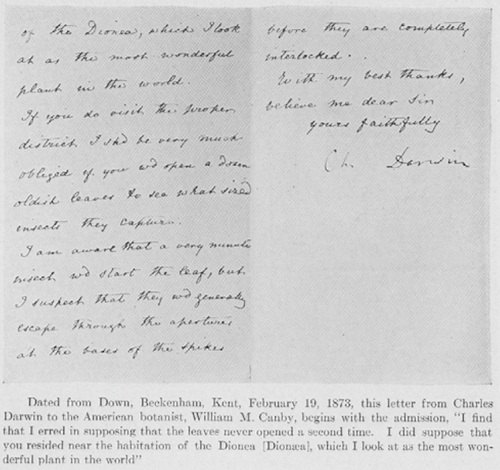

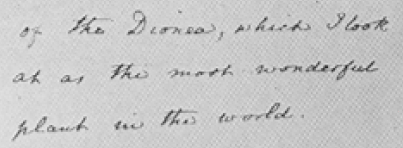

Venus Flytraps are native only to a small region of swampy, coastal North and South Carolina. So that’s one reason to put them on the Evolution 2014 banner. But why that species and not some other endemic species? Obviously, Reason #1 is that flytraps are just awesome, but reason #2 is that Charles Darwin himself realized they were awesome, famously calling the Venus Flytrap “the most wonderful plant in the world.” (I believe this is the original letter, although the Darwin Correspondence Project does not have the full text online yet. The letter was published in Natural History in 1923 by Frank Morton Jones; Harvard Forest has conveniently put the article online at this website, direct PDF link)

Here’s the actual quote, in Darwin’s handwriting!

Here’s the full page of the letter (click to zoom).

…and Jones (1923) has some great commentary reviewing the correspondence between Darwin, Asa Gray, and Canby, including material on how it was Darwin who figured out that the gaps between the teeth of the Flytrap probably had the function of letting small insects escape, after which the trap could reopen without undergoing an expensive digestion step – whereas large beetles and the like were trapped by their size and doomed to a grisly death and digestion in an acid bath.

Short version of what Gray says to Canby about Darwin:

Darwin has hit it. I wonder you or I never thought of it… Think what a waste if the leaf had to go through all the process of secretion, etc., taking so much time, all for a little gnat. It would not pay. Yet it would have to do it except for this arrangement to let the little flies escape. But when a bigger one is caught he is sure for a good dinner. That is real Darwin! I just wonder you and I never thought of it. But he did.

(Asa Gray, writing to Canby, quoted by Jones 1923, p. 595, emphasis original)

As careful scholars, but not creationists, have long observed: Darwin made important scientific advances in lots of areas, not just the theory of evolution.

There’s another reason evolutionists love Venus Flytraps: we know, basically, how the trap evolved! The basic story is pretty obvious to anyone familiar with the traps of the relatives of Venus Flytraps. The closest relative, Aldrovanda, also has a snap-trap, but an aquatic version. Since Dionaea and all of the other relatives are terrestrial, we can infer that the ancestor of the two snap-traps was all terrestrial, although very likely living in swampy, often-flooded ground, like Dionaea and a great many other carnivorous plants.

The next closest relatives are the species of the genus Drosera, the sundews. They catch their prey by secreting sticky glue; once something is caught in the glue, the leaves slowly curl around the prey and digest the victim. There is a huge amount of variability of the closing times of Drosera (of which there are hundreds of species), ranging from days to minutes. Perhaps being stuck in glue and then waiting for days to be digested would be an even more horrifying end for the hypothetical intelligent bug victim, but it would be decidedly less dramatic for the silver screen.

Even more distant relatives are still carnivorous, but lack motion – they either have sticky leaves without motion (genera Drosophyllum and Triphyophyllum), or are pitcher plants (Nepenthes; interestingly, a few of these are actually “sticky pitchers”, indicating that trapping strategies should not be overly essentialized).

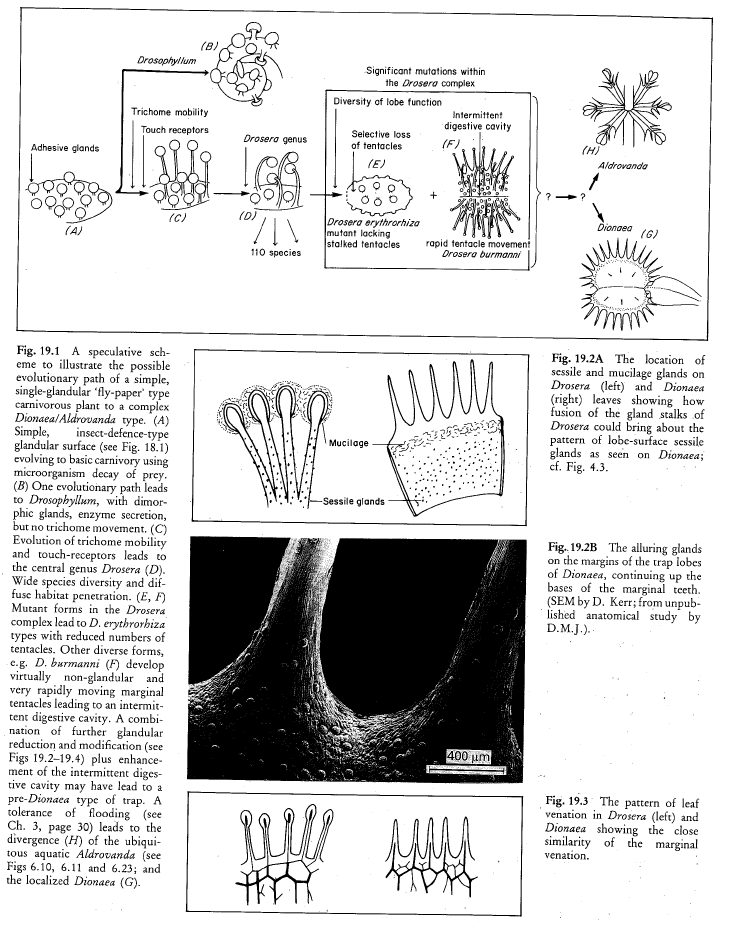

Knowing just this information, the basic story is pretty clear to an evolutionist. In the massive 1989 review book Carnivorous Plants by Juniper et al., which reviewed all work up to that point, but which was published just before molecular phylogenetics took off, the story was clear enough to diagram:

Figure 19 from Juniper et al. (1989), Carnivorous Plants. Shows the evolutionary origin of the Venus flytrap, Dionaea muscipula.

What happened when molecular phylogenetics was applied to carnivorous plants? Well, a new test of the hypothesis was available. Cameron et al. (2002) showed the results:

Figure 3 from Cameron et al. (2002), showing the phylogeny of the Venus Flytrap (Dionaea) and related carnivorous and non-carnivorous plants.

It’s a simple story: first there were plants that trapped with glue, then some of them added the ability to move, and in one surviving lineage, the moving ability became so advanced that glue secretion was no longer needed, and was lost. If, like your typical lazy creationist advocate, all you look at is the Venus Flytrap and some non-carnivorous plant, then the evolution of the flytrap looks like a complete mystery: how could all of those parts come together at once, and how would you have a functioning trap before all the parts came together? Well, here, we had a part, glue, that was essential early on, but later became redundant and was lost. As Pete Dunkleberg pointed out way back in 2003, this is an example of the “scaffolding” route to an allegedly “irreducibly complex” system.

There is a lot more that could be said about the detailed facts that support this basic model – especially about recent work inter-relating the “slow” motion of leaves (shared between Dionaea and Drosera) and how Dionaea uses the slow motion to set off the fast motion of mechanical “snapping” of the leaf, and how this trick was independently discovered in some Drosera with “snap tentacles” (see this amazing YouTube video, and others).

However, this is Halloween, so we’re going for scary, not endless science details. Here’s what’s scary: guess who figured out the evolution of the Flytrap first? Here’s the quote:

CONCLUDING REMARKS ON THE DROSERACEAE.

The six known genera composing this family have now been described in relation to our present subject, as far as my means have permitted. They all capture insects. This is effected by Drosophyllum, Roridula, and Byblis, solely by the viscid fluid secreted from their glands; by Drosera, through the same means, together with the movements of the tentacles; by Dionaea and Aldrovanda, through the closing of the blades of the leaf. In these two last genera rapid movement makes up for the loss of viscid secretion.

[…]

It is a strange fact that Dionaea, which is one of the most beautifully adapted plants in the vegetable kingdom, should apparently be on the high-road to extinction. This is all the more strange as the organs of Dionaea are more highly differentiated than those of Drosera; its filaments serve exclusively as organs of touch, the lobes for capturing insects, and the glands, when excited, for secretion as well as for absorption; whereas with Drosera the glands serve all these purposes, and secrete without being excited.

[…]

The parent form of Dionaea and Aldrovanda seems to have been closely allied to Drosera, and to have had rounded leaves, supported on distinct footstalks, and furnished with tentacles all round the circumference, with other tentacles and sessile glands on the upper surface.

pp. 355-6, 358, 360

Who came up with this model? Why, it was Chucky Darwin himself, way back in his 1875 book Insectivorous Plants, or approximately 110 years before anyone else thought of it (the next suggestions of this model that I have found are a 1985 short piece by Ian Snyder in Carnivorous Plant Newsletter, followed by the work of Juniper and others, in the book and related articles from the late 1980s).

While we’re on the topic, it is worth noting that Darwin’s Insectivorous Plants was, pretty much, the book that codified the whole idea that “carnivorous plants” were a thing, i.e. a coherent phenomenon worthy of a name and dedicated comparative study. While Hooker and other botanists were of course in the know before this (Darwin’s friend Hooker was the one to do the first big review of pitcher plants, something certainly prearranged by the two of them) it was Darwin’s book that seems to have brought the whole subject to the broad attention of the public, for which the whole idea of plants that moved and ate things was deeply counter-intuitive.

In other words, as Gray said, “Darwin has hit it.”

Or, in creationist translation, “AAAAIIIIEEEEEE!!!! It was Darwin himself who framed the entire phenomenon of carnivorous plants which we are now trying to use against him, and furthermore he answered our question about the origin of the Venus Flytraps trap a hundred years before we thought to ask it. The horror! The horror!”

.

.

The most wonderful barnacle in the world

There’s another interesting passage in Darwin’s Insectivorous Plants in “Concluding Remarks on the Droseraceae”:

There can hardly be a doubt that all the plants belonging to these six genera have the power of dissolving animal matter by the aid of their secretion, which contains an acid, together with a ferment almost identical in nature with pepsin; and that they afterwards absorb the matter thus digested. This is certainly the case with Drosera, Drosophyllum, and Dionaea; almost certainly with Aldrovanda; and, from analogy, very probable with Roridula and Byblis. We can thus understand how it is that the three first-named genera are provided with such small roots, and that Aldrovanda is quite rootless; about the roots of the two other genera nothing is known. It is, no doubt, a surprising fact that a whole group of plants (and, as we shall presently see, some other plants not allied to the Droseraceae) should subsist partly by digesting animal matter, and partly by decomposing carbonic acid, instead of exclusively by this latter means, together with the absorption of matter from the soil by the aid of roots. We have, however, an equally anomalous case in the animal kingdom; the rhizocephalous crustaceans do not feed like other animals by their mouths, for they are destitute of an alimentary canal; but they live by absorbing through root-like processes the juices of the animals on which they are parasitic.*

* Fritz Müller, ‘Facts for Darwin, ‘ Eng. trans. 1869, p. 139. The rhizocephalous crustaceans are allied to the cirripedes. It is hardly possible to imagine a greater difference than that between an animal with prehensile limbs, a well-constructed mouth and alimentary canal, and one destitute of all these organs and feeding by absorption through branching root-like processes. If one rare cirripede, the Anelasma squalicola, had become extinct, it would have been very difficult to conjecture how so enormous a change could have been gradually effected. But, as Fritz Müller remarks, we have in Anelasma an animal in an almost exactly intermediate condition, for it has root-like processes embedded in the skin of the shark on which it is parasitic, and its prehensile cirri and mouth (as described in my monograph on the Lepadidae, ‘Ray Soc.’ 1851, p. 169) are in a most feeble and almost rudimentary condition. Dr. R. Kossmann has given a very interesting discussion on this subject in his ‘Suctoria and Lepadidae,’ 1873. See also, Dr. Dohrn, ‘Der Ursprung der Wirbelthiere,’ 1875, p. 77.

(Darwin (1875), Insectivorous Plants, pp. 356-7).

What the heck is Darwin talking about here? He was talking about carnivorous plants, and then suddenly he’s talking about “rhizocephalous crustaceans…allied to the cirripedes”. Let’s parse this out.

Crustaceans are arthropods; well-known crustaceans include shrimp, crabs, lobsters, barnacles, and very likely insects.

“Cirri-pede” means basically “hairy-feet”, and is the technical term for barnacles, which during their larval stage look like fairly normal crustacean with a head, eyes, and legs:

Cyprid stage of a barnacle (the last stage before sticking to a rock). Source: http://www.mesa.edu.au/friends/seashores/barnacles.html

What makes barnacles weird is that, instead of growing into free-living, hunting adults like respectable crustaceans, they find a comfy rock, glue their head to it, secrete a shell, and eat by filter-feeding from the water with their feathery legs. The resulting headless adult bears almost no external resemblance to its crustacean relatives.

Long before Darwin caught the carnivorous plant bug, and even before he wrote Origin of Species, he had made himself a world expert on barnacles in a series of monographs on living and fossil barnacles. He did this work between 1846 and 1854 (you can see it here, and a summary of it here), and his was the first major modern work on barnacles, as it was only in the 1830s that zoologists realized that barnacles were arthropods; previously they had been thought to be molluscs. Whoops, wrong phylum! Not everything keeps the “bodyplan” it is supposed to have!

How about “rhizocephalous crustaceans”? Well, “rhizo-cephalous” means basically “root-head”, and rhizocephalous barnacles are root-headed. Normal barnacles, while weird, at least retain a few features of the arthropod bodyplan – mostly the legs they are waving around in the water. Rhizocephalous barnacles long ago took their ancestral bodyplan, murdered it, and threw it in a ditch somewhere. Lacking even legs, the rhizocephalous barnacles stick their heads to larger animals instead of rocks, and proceed to grow roots out of their heads and suck nutrition from the animals they are parasitizing.

Asa Gray, in his book Darwiniana, summarized:

While some plants have stomachs, some animals have roots.

Asa Gray (1876), Darwiniana, p. 323

Being parasitized by the head-roots of some crustacean with low respect for the bodyplan concepts of zoologists probably isn’t fun, but it is common – there are nine whole families of rhizocephalans, specializing on parasitizing all sorts of critters.

Rhizocephalans have been in the news latest due to R.R. Helm’s article on Sacculina, the parasitic castrators of crabs.

Haeckel’s drawing of Sacculina rhizoids parasitizing a crab. Source.

Helm captures their biology in the spirit of the season:

Your new tormenter is a member of one of the strangest groups of animals known. The adult female body of the rhizocephalan is twisted and deformed, not resembling in any way its barnacle cousins living on rocks near shore. She has lost her hard shell, her legs, her eyes, and transformed into sickly yellow roots and sinuous twisting filaments that are slowly grow like black mold through your tissues.

[…]

Just when it seems it couldn’t be worse, your abdomen explodes. You’re now sterile, and her gonads are erupting out from where your genitals are. Her tumorous ovaries now attract a male rhizocephalan larva, who injects his own cells into her. These grow into testicles within her body. She now has everything she needs for her next takeover.

But none of this bothers you now. She has woven her threads through your brain. She’s been secreting chemicals to control you-you’ve forgotten who you are. You now believe you are female, and the bulge in your abdomen is a brood of your own eggs. Moreover, you are about to give birth. You care for and clean these eggs, as if they were your own.

That’s enough to scare anyone, but I think it’s a particularly scary thing for people with a tendency towards typological views about “phyla” and “bodyplans”. This includes creationists, but also, to a degree, some leading biologists, generally those with precladistic educations. I’ve been on the general “down with phyla!” stump several times before, but Sacculina and the other rhizocephalan barnacles make the point even more directly. For example, the assertion is often made that the “phyla” arose in the Cambrian, and that none arose after that. This is often taken to suggest that the basic animal “bodyplans” arose in the Cambrian, and none arose after that. While it’s clear to me that rates of morphological evolution were higher in the Cambrian, it’s far from clear that “phylum” and “bodyplan” are coherent concepts. What we have is a mixture of concepts – morphological differentness, and monophyletic groups of a certain age. These have been combined in modern usage, basically because almost everyone agrees that named taxa should be natural and not artificial groups; i.e., they should be monophyletic.

What the monophyly requirement does, though, is eliminate any chance of “new bodyplans” being recognized even if they do appear in evolutionary history. For example, if there ever is a case in animal evolution where a “new bodyplan” does arise – something really weird morphologically, that bears no resemblance to the other bodyplans – then, without the monphyly requirement, we would be free to call it a new phylum. Under this situation, we might well discover that new “bodyplans” do originate at some rate, even if the rate is lower than in the Cambrian, and even if it is a somewhat subjective call about what constitutes enough different to constitute a “new” bodyplan.

However, with the monophyly requirement, then as soon as taxonomy advances to the point where the really weird critter is found to be a subset of some other phylum, then the phylum containing the weird critter disappears, as does any chance of a “phylum” originating after the Cambrian! This kind of thing has happened enough times that there is even a list on Wikipedia of “Groups formerly ranked as phyla” (and I’m pretty sure it’s an incomplete list). I assume the artist formerly known as Prince is a fan of these ex-phyla.

To sum up: not only is Sacculina a terrifying monster that will invade an organism’s body, explode its gonads, take over its brain and make it brood more parasites, it also does just about the same thing to the still-popular concepts of “phylum” and “bodyplan”. Creationists and typologists, beware! Eeeeeek!

.

.

The terror of being stuck on a boat with…

I’ve mostly been trying to scare the creationists and the squeamish here, but here’s one for the evolutionists. You know those horror movies where someone is stuck on a boat with a ghost/pirate/murderer/monster?

Well, imagine you’ve signed up for a relaxing summer cruise in Alaska. You will see glaciers and whales and sea otters, and enjoy the beauty of nature and learn a little biology while you’re at it. Then you realize, to your horror, that you are on this boat:

It’s a once-in-a-lifetime chance: participate in a floating conference about intelligent design, with some of the world’s most stunning natural scenery as a backdrop. What better place and what better time – Alaska at the height of summer! – to meet the stars of Discovery Institute and learn in depth about the ultimate questions that science has ever asked: How did the universe begin? How did life arise? How did complex life develop?

Explore these subjects and much more on the first ever Discovery Institute cruise. That’s July 26 to August 2. Make your reservation now!

Join us for a fantastic opportunity to learn about the beauty and design in nature while experiencing it first hand. This weeklong conference will take place on Holland America’s splendid and luxurious Westerdam ship, and will take participants from Seattle to Alaska, and back. Featured speakers will include Dr. Stephen C. Meyer, New York Times bestselling author of Darwin’s Doubt: The Explosive Origin of Animal Life and the Case for Intelligent Design, and renowned Oxford University mathematician and author Dr. John Lennox.

We’ll be announcing more speakers in the near future. The theme of the conference will be “Science & Faith: Friends or Foes?”

Space is extremely limited. Reserve your room now to get the best selection and pricing!

(Source: DI, formatting original)

A week trapped on a boat with the stars of the Discovery Institute! Suddenly Sacculina doesn’t look so bad!

.

.

Update 11/5/13:

Joe Felsenstein contributes some additional details on the history of barnacle taxonomy here. Lamarck removed barnacles from molluscs in 1812, but put them in their own independent group. This made both barnacles and molluscs both of rank “Class”. The rank “Phylum” apparently didn’t exist until Haeckel invented it.

(Also fixed some typos. Ugh!)