Y and mtDNA are not Adam and Eve: Part 3 - Resolving a discrepancy

Part 1: Y and mtDNA are not Adam and Eve.

Part 2: What it means to be the Most Recent Common Ancestor (MRCA)

On to part 3. Except, what’s this? Someone has beat me to it? Gasp!

Okay, go read Dienekes’ Anthropology blog post about the two recent Y papers. I agree with all of the critiques and summaries of both the Poznik et al. (2013) and the Francalacci et al. (2013) papers. Perhaps the best part of this summary:

“And, indeed, the fact that the two are of different ages is not particularly troubling or in need of remedy, since for most reasonable models of human origins we do not expect them to be of the same age.”

But, let’s see if I can provide a little more background (you did go read Dienekes’ post, right?). Good. But, just in case you didn’t, a brief summary of some of the findings of Poznik et al. (2013):

Poznik et al. sequenced a lot of Y chromosomes

Poznik et al sequenced the Y chromosomes of 69 people. Yes, this is more than enough individuals to address this question of the time to the MRCA. Very few lineages, even two can allow us to estimate the time to the most recent common ancestor. Each lineage will contain information (mutations) that have accumulated since they diverged. But, comparing closely related lineages will lead to a lower TMRCA, while comparing very divergent lineages will lead to an older TMRCA. You can learn a lot about the process of how the Y chromosomes diverged by having the intermediate lineages, but they aren’t necessary for computing the TMRCA.

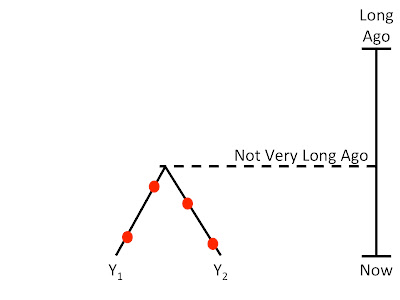

In the pictures below, the red dots are observed mutations.

If there aren’t very many mutations between two regions, then their TMRCA will not be very long ago:

|

| Comparing two closely related lineages gives a younger TMRCA |

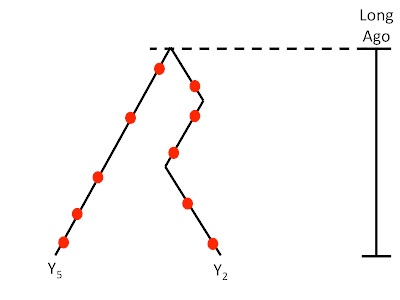

If more Y chromosomes are analyzed from very different regions, then more mutations will be observed between any pair of lineages, and the TMRCA will be older.

|

| The more diverged the lineages, the older the TMRCA |

But, for just estimating the TMRCA, the total number of lineages will have very little (if any) effect on the age estimated, whereas the number of differences observed on the most diverged Y chromosome will be very important.

|

| For estimating TMRCA, the most diverged lineage (Y5) will have the biggest effect. |

How to estimate the time to the most recent common ancestor (TMRCA)

The time estimated depends very little on the number of lineages (see above). Rather, it is extremeley dependent on:

1) how different the lineages are from one another (how many mutations are observed); and,

2) how quickly those differences are estimate to have accumulated (the rate of mutation).

The Y TMRCA is older than most previous estimates

The time to the most recent common ancestor of the Y chromosome, as computed by Poznik et al. is older than most other estimates. But why?

- The diversity of the Y chromosomes included (the more diverse the Y chromosomes, the older the time to their most recent common ancestor)

- the high sequencing coverage, which means that more mutations can be identified

- The rate of mutation the authors use is 0.82x10-9 mutations per base pair per year (95% CI: 0.72-0.92x10-9 mutations per base per year). This mutation rate is lower than estimates from a Y-linked pedigree (1x10-9 mut/bp/year), and from human-chimpanzee divergence, which lengthens the tree compared to previous estimates. The mutation rate was calibrated assuming that humans reached the Americas ~15,000 years ago. Such an exact timing for the entry of modern humans to the Americas is not yet certain.

The Y TMRCA is not as old as it could be

Mendez et al. (2013) recently described a Y chromosome that is much older (67% w/ 95% CI:35-126%) than all other known Y chromosomes. This Y chromosome has not yet been sequenced to the coverage of the Y chromosomes in the Poznik et al. (2013) paper, and was not included in their analysis. If it were included, all other factors remaining the same, the TMRCA for the Y chromosome would be much older than the TMRCA for the mtDNA in the same paper.

The mtDNA estimate is younger than many other estimates

Although there has been a lot of discussion of the Y chromosome being older than previous estimates, I haven’t seen a lot of discussion about the mtDNA, which at 99-148,000 years in this analysis, is estimated a bit younger than previous work (~200,000 years ago). Part of this younger estimate can be contributed to the calibrated mutation rate used. The authors compute a calibrated mtDNA mutation rate of 2.3x10-8 mutations per base pair per year (95% CI: 2-2.5x10-8 mut/bp/year), which is higher than some previous estimates (e.g., 1.7x10-8) - meaning the total tree will be somewhat shorter than previous estimates, all else being equal.

I am excited to see if there exist pockets of mtDNA diversity, such as the highly divergent Y lineage that was recently identified.

So, what is the right mutation rate?

If the mutation rate used across studies varies so much, then it is no surprise that the TMRCA estimates are not consistent across studies. Which one is correct? Well, of course it is__<insert your favorite study>. Okay, so the real answer is that it is not so simple. I know, I know, not the answer you were looking for. It’s like when you have a multiple choice question with four answers and you have to choose the one that is _most correct. I never did well on those. I’ll dodge this bullet by pointing you to a wonderful discussion about human mutation rates by John Hawks.

It is exciting, though, that with the recent ability to isolate and sequence DNA from ancient samples, we should start getting more precise and accurate, estimates of the human mutation rate on the different chromosomes.

One more thing - there is no reason to expect the TMRCA for the Y and mtDNA to be the same.

The process of working backwards to estimate the time to the most recent common ancestor is a paring down of lineages until only one linage remains. This is called coalescent theory. Because they lack recombination, both the Y and the mtDNA represent a single linage, a single coalescent process going back in time. Any number of events could have happened that resulted in a set of mtDNA or Y chromosome lineages being retained longer or shorter than expected. The TMRCA is only the time to the *most* recent common ancestor. There were other ancestors, but we can only identify the most recent. And there are a myriad of reasons why these might not necessarily date to the same time for the Y and mtDNA.

But, why don’t we expect the TMRCA to be the same?

To be clear, it is not that we expect them to be different. More that we don’t expect them to be the same.

I’m going to make a gross over-simplification (we can do more math in the comments, if you like). But, bear with me. Let’s say that you had two dice. If you roll each die once, just once, would you be very surprised if the numbers didn’t match up? No, not at all. Likewise, you wouldn’t be shocked if, say, each die showed a six. And, if one die showed a two, while the other showed a six, you probably wouldn’t call it a discrepancy. Why? Because you only rolled them once.

Similarly (although with a bit more math), when tracing back the Y common ancestor and the mtDNA common ancestor, we should not be surprised if their TMRCAs are different, nor if they overlap.

They represent only one roll of the dice.

————————————-

Science. 2013 Aug 2;341(6145):562-5. doi: 10.1126/science.1237619.

# Sequencing Y chromosomes resolves discrepancy in time to common ancestor of males versus females.

Poznik GD, Henn BM, Yee MC, Sliwerska E, Euskirchen GM, Lin AA, Snyder M, Quintana-Murci L, Kidd JM, Underhill PA, Bustamante CD.

### Source