The March Remembered

Fifty years ago, on the evening of August 27, 1963, I boarded a chartered bus in Rochester, New York, to travel overnight to the March on Washington. I was in Rochester for the summer as a student programmer. The press was worried about the March – maybe there would be clashes between the marchers and white racists. The New York Times begged the organizers to call off the March. President Kennedy also tried to get it canceled, and only reluctantly endorsed it when the organizers refused to cancel.

We ground through the night on the two-lane roads south from Rochester and down along the Susquehanna River through central Pennsylvania – no freeways on that route then. There was little talking, most of us were desperately, and unsuccessfully, trying to get some sleep. Little talking, but I imagine a lot us were worrying. Was this event going to bring out only a few people? Would there be clashes with police or racist opponents?

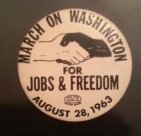

In the morning we reached the outskirts of Baltimore and went down the road to Washington. As the bus entered Washington, some other roads merged with ours. On them I noticed another bus, then another. After I had seen several more it hit me: all these buses were headed in the same direction! There were no buses going the other way. Then more and more and more buses. The Mall near the White House was filled with every bus in the eastern U.S., it seemed. We were directed to a parking place, chosen by some unknown plan. We got off the bus. I bought a pin (I still have it, see the image here), a straw hat that didn’t fit to protect me against the sun, and I was handed a sign to carry: “For an FEPC”. I vaguely knew that that was some sort of call for an equal employment commission, and only realized later how worthwhile that was.

We walked toward the Washington Monument, where a big crowd was gathering on its east side. It was becoming clear that there were lots of people. There was a stage set up near there and lots of people addressed us: A. Philip Randolph, the founder and head of the Pullman Porters Union was one. Folk singers, including Joan Baez led us in song, which was unintentionally funny. The crowd was so big that as we sang along, the people at the back of the crowd were singing one syllable while the people at the front sang the next, so singing in unison didn’t work.

About the time the marching was to start the crowd started moving up the hill towards and past the Washington Monument, down the slope behind it, and along the Reflecting Pool toward the Lincoln Memorial. Everyone just walked along until the density of the crowd stopped them. I was nearly at the large planter on the left front of the Lincoln Memorial. Nearly forty years later I was walking with my brother Lee near the Lincoln Memorial and he proudly pointed out where he had stood on that day. Until then, I had not known he had been there. We both came there, stood not 200 feet apart, and then he went back to Philadelphia and I went back to Rochester, and for years neither of us knew the other had been there.

The crowd was in a good mood, since the March was a success, the police were unobtrusive and no klansmen had turned up. Thousands upon thousands of African-American trade unionists in white “garrison caps”, delegations from African-American churches, white supporters like me. The main dangers were sunburn, heat exhaustion, or failing to find your bus at the end. The speeches started. Of course today the whole civil rights movement is remembered as one speech by one person: Martin Luther King said “I have a dream”, and then everything was OK. But I remember two good speeches that day. The other was by John Lewis, the head of SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. It was a militant speech – later we found out that its most pointed criticisms of the two political parties had been censored.

Organizations like SNCC, CORE, and the SCLC sponsored organizers, many of them African-American college students. They led voter registration drives, attempts to desegregate businesses, defense of people who had been jailed, and protests against attacks on the African-American community throughout the South. The participants in those efforts were mostly local members of the African-American community. They did this at incredible cost: they were risking arrest, attacks, arson, bombings, loss of their livelihoods and loss of their lives. Those hundreds of thousands of people were the true heroes of that day, and most of them couldn’t be there at all. They were a mass movement, not just one man making a speech.

The event was over, and miraculously I found my bus. Near midnight we arrived back in Rochester. I remember the event fondly, but I am much more deeply moved by all the people, mostly in the South, who got arrested, beaten, murdered, burned out of their houses or businesses, fired from their jobs, or forced to move away from their hometowns. And the larger number of people who went ahead anyway, knowing they might face that. They had a dream.