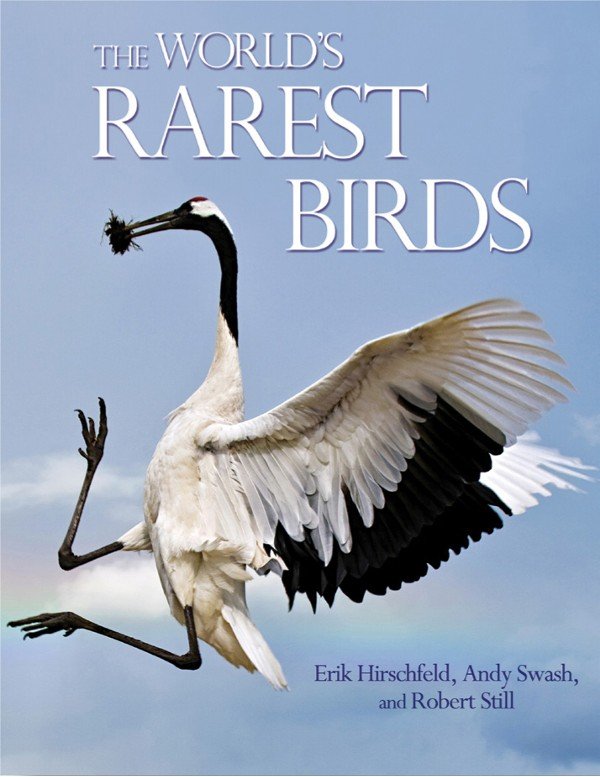

The world's rarest birds

Photograph by Huajin Sun.

Note added May 21, 11:00 a.m., MDT: You may see the contest winners here and the winners of a second contest here.

The editors of this splendid book sought photographs of as many endangered bird species as possible. To that end, they organized a photography contest and garnered over 3500 entries from more than 300 photographers and selected more than 500 photographs for inclusion in the book. The 7 contest winners are displayed in the frontispiece to the book, but frankly they have little or nothing over a great many of the other photographs in the book.

The World’s Rarest Birds is a big book at 8.5 x 11 in (approximately A4) and 330 pages, not counting acknowledgments, index, and whatnot. It is well printed on slick, heavy paper. All but perhaps a dozen or two pages display at least one stunning photograph, and often many. The plumage on many of the birds is remarkable; if you thought that feathers initially evolved for sexual selection, some of these pictures, at a minimum, will reinforce your opinion.

Those who read the book will be like the blind men and the elephant. Photographers will see a photography book. Birdwatchers will see a field guide to rare birds. Conservationists will see extinction. And dilettantes will see a coffee-table book. All will be in some measure correct.

The first chapter is a catchall that outlines the threats to endangered birds, from agriculture, to habitat loss and invasive species, to pollution and mining. The rest of the book is organized by region and provides thumbnail descriptions of each species, its range, its estimated population, and the threats against it. Many of the species are numbered at “<50.” The California condor, for example, numbers 44, but a little green upward-pointing arrow indicates increasing population. The majority of species, unfortunately, are shown with little red downward-pointing arrows that indicate decreasing population.

Like those who Google themselves or look themselves up in the Web of Science, I looked up North America and found in my area the Gunnison sage grouse, which was only recently recognized as a distinct species and which (according to the New York Times) is going extinct, right before our eyes; and the whooping crane, which reportedly has not been seen in Colorado since 2002.

Many of these birds have never had their pictures published before; 75 were drawn so meticulously that you cannot tell them from a photograph. I am afraid that many of these species will be gone by the time this book goes into a second edition.