Musings from the mind of a mouse

Casey Luskin is such a great gift to the scientific community. The public spokesman for the Discovery Institute has a law degree and a Masters degree (in Science! Earth Science, that is) and thinks he is qualified to analyze papers in genetics and molecular biology, fields in which he hasn't the slightest smattering of background, and he keeps falling flat on his face. It's hilarious! The Discovery Institute is so hard up for competent talent, though, that they keep letting him make a spectacle of his ignorance.

I really, really hope Luskin lives a long time and keeps his job as a frontman for Intelligent Design creationism. He just makes me so happy.

His latest tirade is inspired by the New York Times, which ran an article on highlights from the coelacanth genome. Luskin doesn't think very deeply, so he keeps making these arguments that he thinks are terribly damaging to evolution because he doesn't comprehend the significance of what he's saying. For instance, he sneers at the fact that we keep finding conserved elements in the genome, because as we all know, there are lots of conserved elements.

Hox genes are known to be widely conserved among vertebrates, so the fact that homology was found between Hox-gene-associated DNA across these organisms isn't very surprising.

Stop, Casey, and think. Here's this fascinating observation, that we keep finding conserved genes and conserved regulatory regions between mice and fish, which ought to tell you something, and your argument against a specific example is that it isn't rare? It really tells you something when your critics' rebuttal to a piece of evidence is that you've got so much evidence for your position that they're tuning out whenever you talk about the detais.

This is Luskin's approach to every example given in the NY Times article: 'Yeah? So? There are homologous genes all over the place!' I think Luskin might just live forever, which thrills me to pieces. He could get into a running gun battle with a mob from Answers in Genesis, be riddled with bullets, and he'll just point to a nick in his ear and say, "Yeah, so? This one didn't kill me!" and then dismiss all the other wounds because they're so common that no one should care any more. It is truly the logic of immortals.

The specific example he's addressing in his dismissal of Hox conservation, though, is a region of DNA that may play a role in mammals in the formation of the placenta. Luskin pooh-poohs the relevance of this observation by highlighting what we don't know, rather than the evidence at hand.

The authors aren't sure exactly what this particular segment of DNA does, though it's probably a promoter region. In mice the corresponding homologous region is associated with Hox genes that are important for forming the placenta. Ergo, we've solved the mystery of how the placenta evolved. Right?

Not really. Again, all that was found was a little homologous promoter region in Hox-gene related DNA in these two types of organisms. Given that we don't even understand exactly what these genes do or how they work, obviously the study offered no discussion of what mutations might have provided an evolutionary advantage. No evolutionary pathway was proposed, or even discussed. So there's not much meat to this story, other than a nice little region of homology between two shared, functional pieces of Hox-gene-related DNA. But of course, such shared functional DNA could be the result of common design and need not indicate common descent or Darwinian evolution.

He's right that this genetic sequence does not "solve the mystery" of the placenta, but then the authors of the original sequence analysis paper do not claim that it does. There's a lot that we don't know about the translation of any genetic sequence into a morphological feature, but that doesn't mean we know nothing — the paper is talking about stuff that we actually learned from comparing the genomes of different organisms.

We have identified a region of the coelacanth HOX-A cluster that may have been involved in the evolution of extra-embryonic structures in tetrapods, including the eutherian placenta. Global alignment of the coelacanth Hoxa14-Hoxa13 region with the homologous regions of the horn shark, chicken, human and mouse revealed a CNE just upstream of the coelacanth Hoxa14 gene. This conserved stretch is not found in teleost fishes but is highly conserved among horn shark, chicken, human and mouse despite the fact that the chicken, human and mouse have no Hoxa14 orthologues, and that the horn shark Hoxa14 gene has become a pseudogene. This CNE, HA14E1, corresponds to the proximal promoter-enhancer region of the Hoxa14 gene in Latimeria. HA14E1 is more than 99% identical between mouse, human and all other sequenced mammals, and would therefore be considered to be an ultra-conserved element. The high level of conservation suggests that this element, which already possessed promoter activity, may have been coopted for other functions despite the loss of the Hoxa14 gene in amniotes

What they are saying is that they found a region of DNA that is remarkably highly conserved between coelacanths and humans, and that among them are Conserved Non-coding Elements (CNEs), DNA that is not translated into proteins but instead is likely to be important in switching genes off and on. What they found is that this switch is linked to a particular gene, Hoxa14, in the coelacanth which is completely absent in mammals…but the switch still exists, but is now coupled to a gene associated with the formation of extra-embryonic membranes, like the placenta.

The key point is the known information: this snippet of DNA is highly conserved across all vertebrates, but the gene it is associated with has decayed in sharks and disappeared entirely in tetrapods. The question is how the switch has persisted: Luskin's preferred explanation is that God spliced this particular piece of DNA into every vertebrate species; the scientific explanation is that it shows a pattern of shared history, and that its role is conserved in tetrapods because it has found a novel function in regulating a different gene.

So far, this is nothing but Luskin-levels of ignorance and incomprehension. Let us now dive deep into Luskin-levels of outright stupidity and dishonesty.

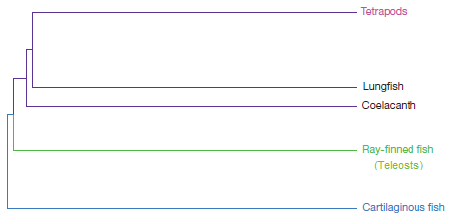

The paper includes this diagram of the evolutionary relationships of various vertebrate species.

These are the relationships determined by comparisons of large portions of the entire genomes of these organisms — it's a phylogeny based on a large amount of data. Luskin obligingly simplifies it for us:

The closest relative to us tetrapods are lungfish, with coelacanths more distant, and teleosts further still. This is the consensus. It's supported by many comparisons.

But brace yourself: here's where Luskin proves that he's an idiot. He sets aside the synthesis of large data sets, and instead explains that if we look at single genes, evolution is proven wrong!

He read the paper and found a couple of examples interesting genes that were highlighted by the authors themselves. In particular, they cite examples of gene losses. All other vertebrates have a component of the immune system, a gene called immunoglobulin M (IgM), but coelacanths are unusual in lacking this particular gene. There's another immune system component, IgW, which seems to be a relatively primitive or ancestral immunoglobulin, which we tetrapods lack, and which is also missing in teleosts, but is found in coelacanths and sharks.

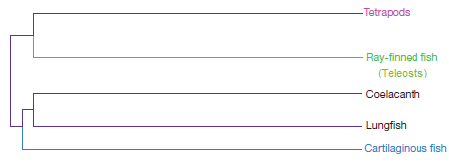

So what does Luskin do? He redraws the whole vertebrate phylogeny based on a single gene. He throws away almost the entire data set, and focuses on a single character.

But in an IgW-based tree, tetrapods should be much more closely related to goldfish than to the coelocanth or the lungfish. That's startling and unexpected -- if you're a proponent of common descent.

Holy crap. That's simply a lie. No: if you look at individual genes, this is exactly what we expect to see, and we're completely unsurprised. Every single gene is not expected to change in lockstep with speciation events, and each lineage can experience the loss of subsets of genes independently of the larger clade. What Luskin is claiming is utterly contrary to everything any evolutionary biologist will tell you.

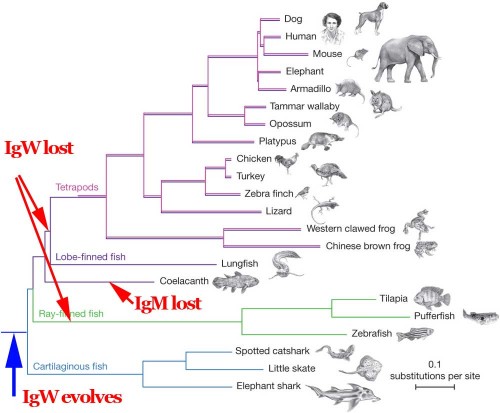

Here's the original phylogeny from the Amemiya paper. I've just added a couple of arrows to indicate simple events in the history of the IgM and IgW genes.

The simplest, most parsimonious explanation is that IgM and IgW were present in the last common ancestor of all of these organisms. The IgW distribution in extant forms is explained by two independent gene losses, one in the ancestor of all tetrapods and another in the ancestor of all teleosts. The IgM distribution is explained by a unique loss in the ancestor of the two modern species of coelacanths. This is trivial and totally unsurprising, requiring no magic, no all-powerful designer, and no processes other than known natural mechanisms of mutation.

Luskin, however, finds this improbable.

Of course this requires some extremely unparsimonious and unlikely events. Since IgW is found in vertebrates as diverse as lungfish and cartilaginous fish (e.g., sharks), a Darwinian evolutionary view would infer that the gene for IgW was present in the ancestor of all jawed vertebrates. If so, then IgW must have stuck around in vertebrates long enough to end up in the sarcopterygian line. But somehow evolutionary theory must explain why tetrapods and all teleosts lack this gene.

"Unparsimonious"? You keep using that word. I don't think it means what you think it means.

The evolutionary explanation requires three mundane events, the simple loss of a gene in an ancestral population.

The Intelligent Design creationist explanation requires that every extant species was specifically and intentionally stocked with a set of genes hand-chosen by a designer. God magically inserted IgM into each vertebrate species, except that he missed the coelacanths, and he magically inserted IgW into each and every shark, ray, coelacanth, and lungfish, but he intentionally left them out of every tetrapod and teleost.

And Luskin chooses to lecture biologists on the meaning of "parsimonious"? That's startling, but entirely expected from the frauds at the Discovery Institute.