Lab Notes: The Alias Method for Sampling from Discrete Distributions

I am a computational evolutionary geneticist, and in my research I develop software to analyze genetic data and study evolutionary questions. As part of my research, I work with a lot of simulation programs to generate evolutionary datasets. My most widely used program is Dawg, and I am currently putting the finishing touches on a new version.

In simulating molecular sequences, you start by simulating the ancestral sequence at the root of a phylogenetic tree and then evolve that sequence upwards, making point mutations and indels as you go. Depending on type of sequences being generated, the root would be a string of nucleotides, amino acids, or codons. To simulate the root sequence, we draw its characters from a discrete, stochastic distribution. For example, lets say that in your system the frequencies of A, C, G, and T are 26%, 23%, 24%, and 27%. In order to create a root sequences of length k, you simply sample k nucleotides from this distribution, e.g. AAGTGCA or GATTACA.

Therefore, the key step in the simulation of the root sequence is sampling repeatedly from an arbitrary discrete distribution. While I have been doing this for years, I recently went searching for doing it better and came across the following excellent article: Darts, Dice, and Coins, written by Keith Schwarz, a lecturer at Stanford. In this article, he describes many different methods for sampling from a discrete distribution and analyzes their performance. It turns out the best method is the Alias Method, first described in the 1970s and improved by M. Vose in 1991. I will describe it below, but before we get there, here are some alternatives.

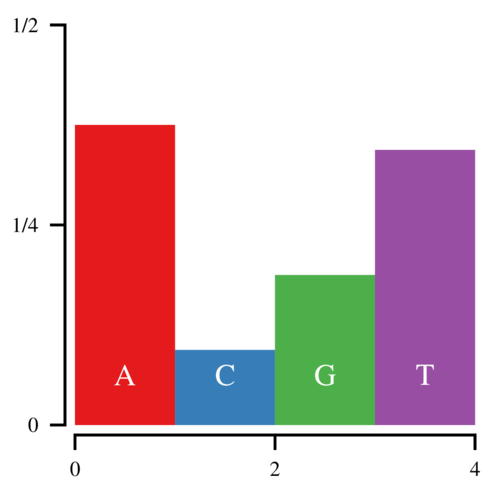

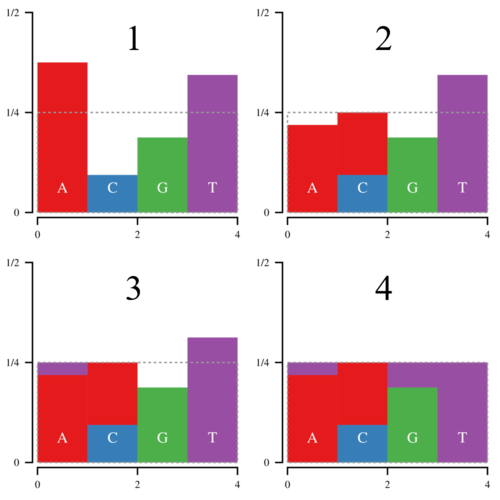

Imagine that you want to sample from the following discrete distribution of nucleotides:

Let the heights of these bars be h0, h1, h2, and h3. Since these heights correspond to the probability that a random base is A, C, G, or T, the total area of the histogram is 1. Now to sample from this histogram, you can draw a uniform random number—call it u—between 0 and 1 and find which bar corresponds to that number. If u < h0, you sample an A. If u < h0+h1, you sample a C, etc. This works, but is clearly inefficient since it requires you to search through the histogram from left to right every time you sample a nucleotide. Imagine if you were sampling from 64 codons.

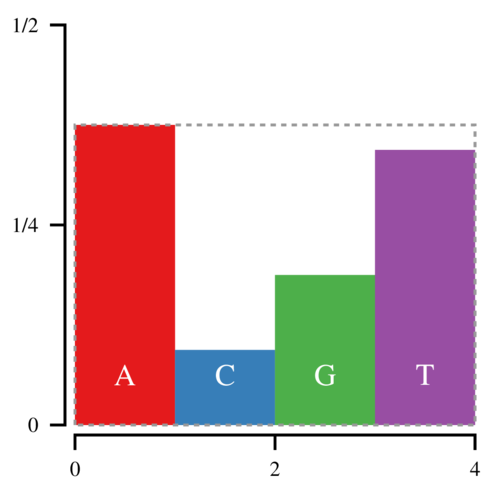

A more efficient method is to sample a point uniformly in a box that contains all the bars:

The (x, y) coordinates of the sampled point are defined by uniform random numbers between [0, 4) and [0,3/8) respectively. If this point lands in the white space, you reject it and try again. This approach is more efficient because once you have chosen x, you only need to compare y against hfloor(x). However, the white space makes up one third of the space in this box, and thus on average you will have to sample 1.5 points for every sampled nucleotide.

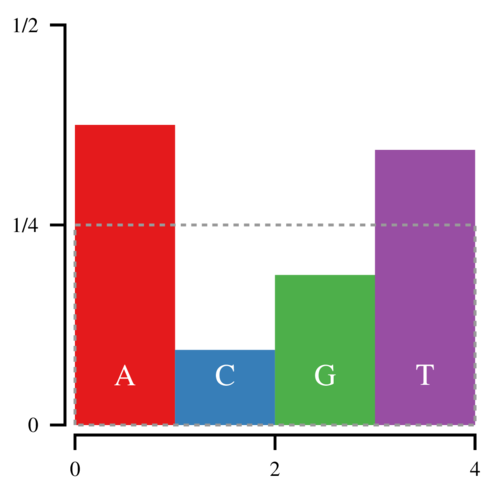

With the Alias Method, we can bring this down to 1 point for every sampled nucleotide. Start by constructing the following box, which has an area of 1.

Notice that the amount of white space within the box is equal to the amount of filled space outside it. Thus it is possible to cut the histogram into blocks and rearrange them such that the entire box is filled.

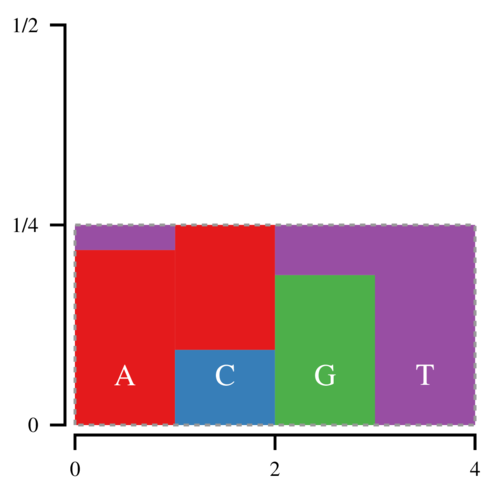

Thus every bar is defined by two regions, the lower, normal region, and the upper, “alias” region. Now we can draw a point (x, y) uniformly inside this box; x determines which bar we look at, and y determines whether we return the normal or the alias value. Since there is no white space, we only have to draw 1 point per sampled nucleotide.

/*

* C++ code for sampling from an alias table

*/

uint32_t a[64]; //aliases

uint64_t h[64]; //bar heights

uint32_t get_codon() {

uint64_t u = rand_uint64();

uint32_t x = u&63;

return (u < h[x]) ? x : a[x];

}

Now the hard part comes in slicing and moving the blocks around. That is where Vose’s method come in. Basically keep a list of bars above or below the top line of the box, called large and small. Then pop an element off of both lists, and use the large element to fill in the small element. If the large element is still above the line, put it back in the large list, otherwise put it in the small list. Repeat until the box is filled. The process looks a bit like this:

While Vose’s method is typically implemented using arrays, (see Darts, Dice, and Coins), array manipulation can be expensive. However, it is possible to implement Vose’s method without using temporary arrays to hold large and small elements. In the code below, I use indices to walk through the histogram linearly. Only three indices are required: g for the current large bar, m for the current small bar, and mm for the next possible small bar. While g and mm keep track of the positions that we’ve examined and never decrease, m sometimes will jump backwards if a large bar has become small. This is the code that Dawg 2.0 is currently using to construct an alias table for codon simulations, and is more efficient than previous solutions.

/*

* Initialize alias table from discrete distribution, pp

*/

void create_alias_table(const double *pp) {

// normalize pp and copy into buffer

double f=0.0, p[64];

for(int i=0;i<64;++i)

f += pp[i];

f = 64.0/f;

for(int i=0;i<64;++i)

p[i] = pp[i]*f;

// find starting positions

std::size_t g,m,mm;

for(g=0; g<64 && p[g] < 1.0; ++g)

/*noop*/;

for(m=0; m<64 && p[m] >= 1.0; ++m)

/*noop*/;

mm = m+1;

// build alias table until we run out of large or small bars

while(g < 64 && m < 64) {

// convert double to 64-bit integer, control for precision

h[m] = (static_cast<uint64_t>(

ceil(p[m]*9007199254740992.0)) << 11);

a[m] = g;

p[g] = (p[g]+p[m])-1.0;

if(p[g] >= 1.0 || mm <= g) {

for(m=mm;m<64 && p[m] >= 1.0; ++m)

/*noop*/;

mm = m+1;

} else

m = g;

for(; g<64 && p[g] < 1.0; ++g)

/*noop*/;

}

// any bars that remain have no alias

for(; g<64; ++g) {

if(p[g] < 1.0)

continue;

h[g] = std::numeric_limits<boost::uint64_t>::max();

a[g] = g;

}

if(m < 64) {

q[m] = std::numeric_limits<boost::uint64_t>::max();

a[m] = m;

for(m=mm; m<64; ++m) {

if(p[m] > 1.0)

continue;

h[m] = std::numeric_limits<boost::uint64_t>::max();

a[m] = m;

}

}

}

Note that if the values in pp were not immutable, then we would not need p.

Note 2012/11/25: updated to fix typos.

Note 2013/05/03: fixed typo.