Continuous geographic structure is real, "discrete races" aren't

Note: This topic is outside of my specialty, so it may be that I have missed some important points. I think I’ve got the basics correct, but this is a very complex topic. I will be interested in critical but constructive posts in the comments.

Update: required reading, which basically confirms my points I think:

Weiss, K. M. and J. C. Long (2009). “Non-Darwinian estimation: My ancestors, my genes’ ancestors.” Genome Research 19(5), 703-710.

Nievergelt, C. M., O. Libiger and N. J. Schork (2007). “Generalized Analysis of Molecular Variance.” PLoS Genetics 3(4), e51.

On Monday, Jerry Coyne at Why Evolution is True posted on “Are there human races?” While acknowledging the very bad history of the race concept in human history, and noting some of the problems with applying the concept to humans, Coyne concluded, basically, that the answer was yes, there are human races. While reviewing Jan Sapp’s piece which concluded that human races did not objectively exist, Coyne wrote:

As Sapp notes, and supports his conclusion throughout the review:

Although biologists and cultural anthropologists long supposed that human races–genetically distinct populations within the same species–have a true existence in nature, many social scientists and geneticists maintain today that there simply is no valid biological basis for the concept. The consensus among Western researchers today is that human races are sociocultural constructs.

Well, if that’s the consensus, I am an outlier. I do think that human races exist in the sense that biologists apply the term to animals, though I don’t think the genetic differences between those races are profound, nor do I think there is a finite and easily delimitable number of human races. Let me give my view as responses to a series of questions.

Unfortunately, while Coyne’s position is admirably clearly expressed, his reasons for accepting race don’t hold up. Some of his commentators have pointed out some of the problems in the comments. My own critique of his position is informed by a symposium I attended in San Francisco last year, “Is There Space for Race in Evolutionary Biology?”, and particularly by the arguments that speakers Massimo Pigliucci and Alan Templeton made there.

Here’s the conference information:

Is There Space for Race in Evolutionary Biology?

The 2011 Spring Conference for the Bay Area Biosystematists

Are human races geographical subspecies? How about distinct evolutionary lineages? What about ecotypes? Does it even make sense to divide humans into subspecies? Can there be biological races in other species even though there aren’t any in humans? This conference aims to answer these questions and more as it explores the question of whether race can be validly defined in the context of evolutionary biology. Come join us at the 2011 Spring Conference for the Bay Area Biosystematists! Please peruse this site to learn more about the conference.

Date: May 14, 2011 Time: 12:45-7pm Location: McLaren Conference Center, Room 250, University of San Francisco

Coyne asks a series of questions and gives answers:

1. What are races? Coyne answers:

“races of animals (also called “subspecies” or “ecotypes”) are morphologically distinguishable populations that live in allopatry (i.e. are geographically separated)”

2. Under that criterion, are there human races? Coyne answers:

Yes. As we all know, there are morphologically different groups of people who live in different areas, though those differences are blurring due to recent innovations in transportation that have led to more admixture between human groups.

3. How many human races are there? Answer:

That’s pretty much unanswerable, because human variation is nested in groups, for their ancestry, which is based on evolutionary differences, is nested in groups.

4. How different are the races genetically? Answer:

Not very different. […]

…but he goes on to cite the evidence of the results of clustering analyses that are often able use genetic data to place humans quite accurately into one population or another. I.e., the argument is basically that if there is enough signal in the genetics to place humans into one population or another, then races exist.

5. Why do these differences exist? Answer:

The short answer is, of course, evolution. The groups exist because human populations have an evolutionary history, and, like different species themselves, that ancestry leads to clustering and branching, though humans have a lot of genetic interchange between the branches!

He goes on to discuss the possible influence of natural and sexual selection on a few traits, and genetic drift and neutral evolution on the rest.

6. What are the implications of these differences? Coyne writes:

Not much. There are some medical implications.

…and goes on to (appropriately) dismiss certain pernicious ideas like the hard-to-kill one that IQ is genetically different between different races. However, he does leave open the possibility that a trait like intelligence could vary genetically between races, although it seems unlikely to him, he says there is no evidence supporting this, and in any event even a statistically-detectable difference between populations would be swamped by the within-population variability in such a trait. (Therefore, even in the event that such a population-level difference was found, one could not safely extrapolate from a race identification to a prediction about an individual.)

The critique

The key problems with the point of view that Coyne presents were made clear, at least to me, by Alan Templeton’s talk on this subject. I went to the talk in a quite skeptical mood, since Templeton is in my judgement on the wrong side of certain issues in phylogeography*. But Templeton’s points on race are simple and pretty convincing. See also:

Templeton, A. R. (1998). “Human Races: A Genetic and Evolutionary Perspective.” American Anthropologist 100(3), 632-650.

Race is generally used as a synonym for subspecies, which traditionally is a geographically circumscribed, genetically differentiated population. Sometimes traits show independent patterns of geographical variation such that some combination will distinguish most populations from all others. To avoid making “race” the equivalent of a local population, minimal thresholds of differentiation are imposed. Human “races” are below the thresholds used in other species, so valid traditional subspecies do not exist in humans. A “subspecies” can also be defined as a distinct evolutionary lineage within a species. Genetic surveys and the analyses of DNA haplotype trees show that human “races” are not distinct lineages, and that this is not due to recent admixture; human “races” are not and never were “pure.” Instead, human evolution has been and is characterized by many locally differentiated populations coexisting at any given time, but with sufficient genetic contact to make all of humanity a single lineage sharing a common evolutionary fate.

Taking Coyne’s points in order, I will summarize what I think Templeton would say, and add my own points.

1. What are races? Are human races “allopatric”? Templeton would deny that human populations “live in allopatry”. Humans are not, in fact, living in discrete, disconnected populations. Instead, humans are pretty continuously distributed from Africa all the way around the globe, and have been since glacial times (the tiny possible exceptions to this statement involve the recent colonization of remote islands e.g. by Polynesians, but this occurred only in the last few hundred-2000 years, a geological eyeblink). And genetic contact, i.e. interbreeding, seems to have been occurring between adjacent “populations” the whole time.

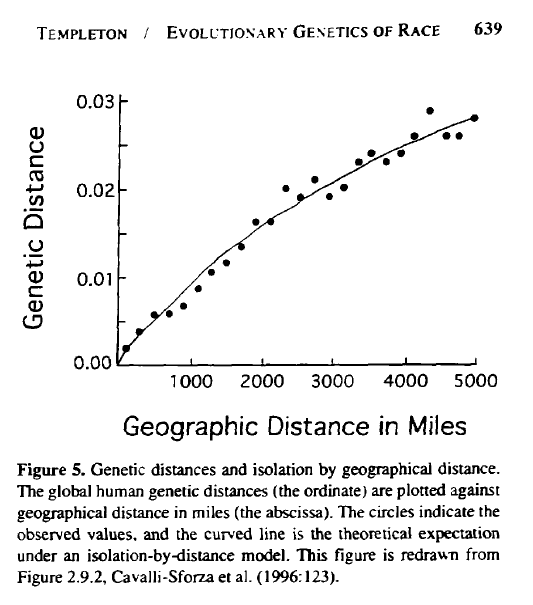

The overwhelming signal in human genetics seems to be isolation-by-distance – the larger the geographical distance between two samples, the greater the average genetic difference. But it is crucial to understand that this is not a confirmation of the idea of discrete races. If races were discrete, if you sampled along a transect, you would sample individuals from race A, A, A, A, and then suddenly switch to race B, B, B, B.

But what we typically see instead, if you sample along a transect, is that humans measured by some index of genetic difference along a transect would produce values with something like 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7. (I am making these numbers up, but imagine that they are a measurement of genetic difference from the first sample, i.e. the difference is 0 at the first sampling location, 1 at a sample 1000 km away, 2 at a sample 2000 km away, etc.)

This is a *crucial* distinction to get before we proceed, so I encourage readers to go back and re-read the previous paragraphs to get the idea into their head. Key concept: if you sample humans along a transect, the typical pattern is that genetic difference will increase in a continuous fashion with greater distance between samples, rather than in large discrete “steps” as you would expect with well-separated allopatric populations, or discrete “races”.

Here’s is Templeton’s depiction of this phenomenon:

2. Under that criterion, are there human races? Coyne answers “yes”, because we can see obvious differences between humans in different locations. But that, by itself, does not establish that the differences are discrete and categorical, which is what would have to be the case for ideas like “counting the number of races” and “distinguishing one race from the next” to make sense. Quite often, geneticists like Coyne seem to be being mislead by the fact that sampling is usually discrete. Usually, scientists go and get some samples from one region in Africa, some samples from one region in Europe, some from a region or two in Asia, etc. Before there was genetic sampling, there were similar issues in skull measurements, photographs, anthropologists’ monographs, etc.

When this form of sampling is done, of course it *looks like* the races are discrete, but what was actually discrete was your sampling. Templeton’s assertion is that if you had sampled on a grid, instead, and sampled all regions equally, you wouldn’t be able to draw discrete lines between races. The pattern would be that closer samples are more related, but this similarity would decline continuously with distance, and not in big discrete steps.

3. How many human races are there? Coyne says the question is “pretty much unanswerable”, and notes that the answers have varied from 3 to over 30. Coyne is correct to say the question is unanswerable, and the reason this is so is easily explained on Templeton’s view. But the unanswerability is quite a puzzle – or ought to be – if one is trying to argue that races are real. If you are going to assert that there is a rigorous and objective and scientific concept called “race”, but you can’t even explain how to objectively identify the races and thus count them, there’s a big problem somewhere.

For example, even though there are all kinds of definitions of “species”, and thus some variation in the count in the number of species, at least (a) the various species concepts are more-or-less objective, and (b) it happens that different concepts will often, although not always, give the same or similar answers. But, it is well-known that if “defining a species” is somewhat difficult and controversial, it is much worse for defining a subspecies, and it is close-to-hopeless for the ubiquitous concept of “population”. There are hundreds of papers on species concepts, but there are almost none published on “population concepts” (this, Millstein 2009, is one of the only ones; see also discussion of the paper). In practice, “populations” of organisms are basically either merely convenient geographic groupings determined subjectively by biologists for convenience or sampling purposes, very often geographically defined; or, they are convenient abstract entities useful for mathematical and computational modeling. But whether or not the “populations” you create for sampling and analysis purposes represent real discrete groups out there in the real world is an empirical question, and it looks like, in the case of humans, there is little basis for assuming discrete populations.

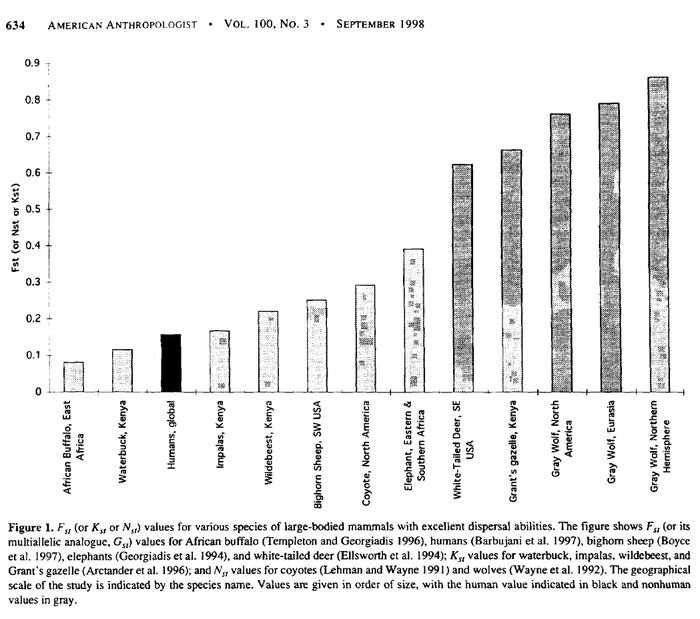

Finally, Coyne asserts at one point in his blogpost that races exist in humans much as subspecies exist in other species. But in terms of genetic divergence, at least, this is difficult to support. Templeton points out that the genetic divergence among living humans is much less than that typically observed between subspecies. This is not controversial or poorly known so I won’t argue this in detail. Templeton (1999) provides a graphical version:

(Note: see further discussion of criticism of Templeton (1998)’s Figure 1 at this comment.)

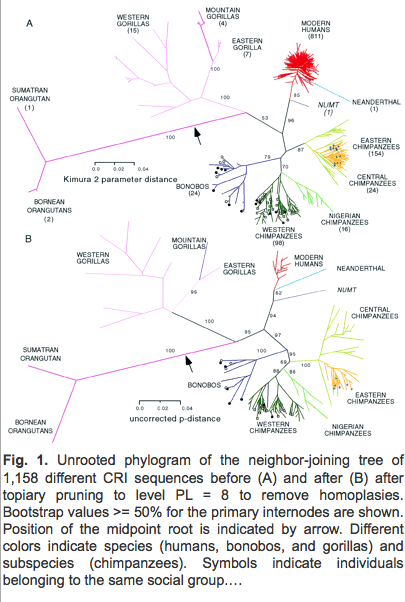

Or, we can compare the branch lengths of a tree of built of the aligned sequences from the mitochondria of humans and our ape relatives:

(From: Gagneux et al. 1999, PNAS; full-resolution figure) (Hat tip: Reed Cartwright)

Now, it is important to remember that the mitochondrial DNA sequence is really just one nonrecombining genetic marker, and it is possible for the mtDNA phylogeny to differ from the true species phylogeny (due to introgression) or to not reflect the pattern of diversity in the nuclear markers. Nuclear alleles coalesce more slowly, and recombination means that nuclear DNA will not have a simple branching phylogenetic history that can be easily represented by a tree, at least not within an interbreeding population. However, my sense of it is that in the great ape group (including humans), the mtDNA accurately represents the overall picture of phylogeny and genetic diversity.

5. Why do these differences exist? Coyne writes:

The short answer is, of course, evolution. The groups exist because human populations have an evolutionary history, and, like different species themselves, that ancestry leads to clustering and branching, though humans have a lot of genetic interchange between the branches!

Obviously we agree that selection, drift, etc. explain the evolution of observed diversity in the human species. But there are important questions here that Coyne doesn’t address. (1) How do we know that we’ve got discrete or even somewhat discrete “populations” which then can be said to have a distinct evolutionary history. Maybe we’ve just got one big interconnected population. This was addressed above. (2) How much interchange do you have to have to have before claims of clustering and branching break down? The evidence seems to indicate that the genetic differences between human “populations” in different regions are primarily a matter of differences in allele frequencies, but where most non-tiny populations have most of the alleles observed in the global population, just with varying frequencies. If this observation is true, this causes a problem for Coyne’s statement, because another way to say “the differences are differences in allele frequencies” is to say that “the differences are not fixed between populations”, and another way to say that is “coalescence has not occurred in these populations for these markers, either because of the lack of time or the presence of gene flow due to migration or both”. Yet another way to say this is to say that “for most loci, these populations are not reciprocally monophyletic”, and if you are a phylogeneticist, you known that this statements is equivalent to saying “your data are not appropriately represented by a single branching tree, instead you have a number of trees representing the individual histories of individual loci in the population”. Yet one more way of saying it is “you don’t have discrete populations, you are sampling within one genetically connected population.”

Coyne mentions clustering results, which have indeed impressed some people, and led to a minor resurgence in the race concept among geneticists in the last decade. It is true that, if you sample a region where people have mostly lived in or near the villages where they grew up for dozens of generations (e.g. parts of Europe, and e.g. not North America), you can take an individual’s genetic data and place their ancestry on the map with a fair degree of accuracy.

And it is also true that a computer algorithm, if given a number of samples from e.g. Africa, Europe, and China, could accurately place the samples into those 3 clusters, if told the number of clusters ahead of time. It is even true that newer algorithms can figure out the number of clusters in the data on their own, e.g. Structurama (full disclosure: authored by my advisor).

These sorts of observations have led a number of geneticists to speak of “Lewontin’s Fallacy” (e.g. Edwards 2003). The geneticist Richard Lewontin famously argued in 1972 that “about 85% of the total genetical variation is due to individual differences within populations and only 15% to differences between populations or ethnic groups” (Edwards 2003). Lewontin argued that this fact made the idea of racial classification irrelevant, since most variation was within groups instead of between them. You can see his point in an intuitive way by imagining that you have a sample of two people. Assuming the 85%/15% distribution of variation, for any one locus that varies between the two individuals, it is much more probable that the difference is just due to within-population variability than due to between-population differences.

Lewontin’s paper and argument have been cited thousands of times – for example, it was cited in just this fashion in the review by Sapp which Coyne is critiquing.

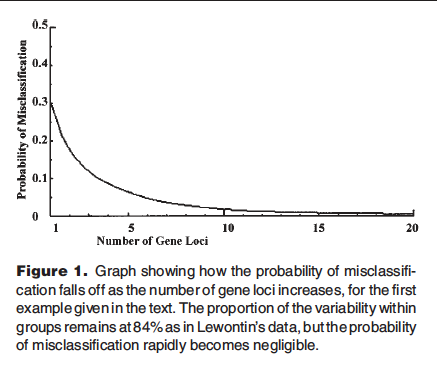

Edwards points out that the problem with Lewontin’s statement is that it is only true if you have only one locus to look at, or if you can safely assume that the variation at all loci is independent. It turns out that if you have, say, dozens or hundreds or thousands of loci to look at, and there is some population structure in the data, for example, population-level differences in allele frequencies, then by looking at all those loci, it becomes quite easy to identify the clusters and to accurately place individuals into them. Edwards describes how this works:

Consider two haploid populations each of size n. In population 1 the frequency of a gene, say “+” as opposed to “-“, at a single diallelic locus is p and in population 2 it is q, where p + q = 1. (The symmetry is deliberate.) Each population manifests simple binomial variability, and the overall variability is augmented by the difference in the means. The natural way to analyse this variability is the analysis of variance, from which it will be found that the ratio of the within-population sum of squares to the total sum of squares is simply 4pq. Taking p = 0.3 and q = 0.7, this ratio is 0.84; 84% of the variability is within-population, corresponding closely to Lewontin’s figure. The probability of misclassifying an individual based on his gene is p, in this case 0.3. The genes at a single locus are hardly informative about the population to which their bearer belongs.

Now suppose there are k similar loci, all with gene frequency p in population 1 and q in population 2. The ratio of the within-to-total variability is still 84% at each locus. The total number of “+” genes in an individual will be binomial with mean kp in population 1 and kq in population 2, with variance kpq in both cases. Continuing with the former gene frequencies and taking k=100 loci (say), the mean numbers are 30 and 70 respectively, with variances 21 and thus standard deviations of 4.58. With a difference between the means of 40 and a common standard deviation of less than 4.6, there is virtually no overlap between the distributions, and the probability of misclassification is infinitesimal, simply on the basis of counting the number of “+” genes. Fig. 1 shows how the probability falls off for up to 20 loci.

This sort of information (obviously the between-population allele frequencies always differ between loci in real life, but this doesn’t matter much for the classification) is what lets the clustering algorithms find their clusters, and place people into them. Edwards concludes:

There is nothing wrong with Lewontin’s statistical analysis of variation, only with the belief that it is relevant to classification. It is not true that “racial classification is… of virtually no genetic or taxonomic significance”. It is not true, as Nature claimed, that “two random individuals from any one group are almost as different as any two random individuals from the entire world”, and it is not true, as the New Scientist claimed, that “two individuals are different because they are individuals, not because they belong to different races” and that “you can’t predict someone’s race by their genes”. Such statements might only be true if all the characters studied were independent, which they are not.

Lewontin used his analysis of variation to mount an unjustified assault on classification, which he deplored for social reasons. It was he who wrote “Indeed the whole history of the problem of genetic variation is a vivid illustration of the role that deeply embedded ideological assumptions play in determining scientific ‘truth’ and the direction of scientific inquiry”.(5) In a 1970 article Race and intelligence(11) he had earlier written “I shall try, in this article, to display Professor Jensen’s argument, to show how the structure of his argument is designed to make his point and to reveal what appear to be deeply-embedded assumptions derived from a particular world view, leading him to erroneous conclusions.”

A proper analysis of human data reveals a substantial amount of information about genetic differences. What use, if any, one makes of it is quite another matter. But it is a dangerous mistake to premise the moral equality of human beings on biological similarity because dissimilarity, once revealed, then becomes an argument for moral inequality. One is reminded of Fisher’s remark in Statistical Methods and Scientific Inference(12) “that the best causes tend to attract to their support the worst arguments, which seems to be equally true in the intellectual and in the moral sense.”

Edwards’s statistical argument is correct, but unfortunately – and ironically for someone criticizing Lewontin for not recognizing a mistake caused by a “deeply-embedded assumption” – Edwards is at least potentially being misled by his own deeply embedded assumption, as are others who argue along the lines of “clustering of humans based on genetics works, therefore different races exist.” Just because an analysis shows that the humans you sample fall into clusters does not necessarily mean that the clusters are out there in the real world in the human population. If the human population basically has continuous genetic variation, with genetic similarity decaying smoothly with distance, then, if your sampling was geographically clustered, your samples will show that structure.

I am not an expert in this area, but my sense of the matter from Templeton’s comments is that it is much more true to say that, at least for humans living basically in their ancestral locations, genetic difference between “populations” is essentially a smooth function of geographic distance. This is definitely “geographic structure” in the human population, but it is not evidence for discrete populations or races. And genetic clustering that is due to clustered sampling (done for convenience, funding reasons, political access reasons, and/or prior assumptions that localized sampling of a region represents that region, because you “already know” that a particular race inhabits that region) cannot be taken as evidence of real discrete structure in the human population.

It is possible that there is some discrete structure – due to language barriers or large migration events or whatever – but I would want to see this explicitly tested for rather than just assumed. And if it exists, it will be important to ask how much of genetic variation this explains, compared to the already major isolation-by-distance effect that we already know about and already know is quite strong.

A little more on clustering

One other point about clustering, this time with hierarchical clustering. Hierarchical clustering algorithms produce groups within groups, which are commonly represented by a tree structure very similar (superficially) to a phylogeny. You will sometimes see the argument that one can take the genetic distances between a bunch of samples of humans, throw them into a hierarchical clustering algorithm, and get a tree out, and therefore we can safely think of human races as subspecies within our species. This matches up superficially with a lot of our background conceptual model of how species can be placed as groups within groups on a phylogeny, and thus tends to reinforce the “races are real” idea in some peoples’ heads.

However, this argumentation is at least dubious. First, clustering methods taken as a phylogenetic method are a form of “distance method”, and distance methods are well-known in phylogenetics to be the crudest sort of phylogenetic method and the one most prone to errors; unless some pretty specific assumptions are met (e.g. molecular clock) they can produce very bad errors. Basically, distance methods rely on the pairwise Euclidean distances between samples in your data space. You can imagine this as the “as the bird flies” distance. However, the distance that we are really interested when we produce a phylogeny is not the “as the bird flies”, Euclidean distance between our samples; instead, we are most interested in the path distance, i.e., the actual mutational steps (or character-change steps) that led from a common ancestor, up each branch, to the tips that we observe. This form of distance is known as a “Manhattan distance”, named after the square street grid in downtown New York. In New York City, you can’t get from A to B by going “as the crow flies”, you have to drive along the street grid, avoiding one-way streets, construction, traffic jams, etc. Only in idea situations will the actual traveled path distance equal or closely approximate or correlate linearly with the as-the-crow-flies distance. Phylogenetic methods are thus really about finding the best paths (branching patterns) between the observed samples, according to some criterion (e.g. parsimony, maximum likelihood, posterior probability).

Therefore, clustering methods are not phylogenetic methods, except in special situations.

Second, a hierarchical clustering method will produce hierarchical clustering from almost any but the most artificially-constructed distance data. If there is true hierarchical structure, the method can find it, but some sort of clustering will be produced, even if it’s poorly supported and changes dramatically under e.g. resampling of the data. And there can be many sources of any clustering that is observed. I bet that you could:

* lay down a latitude/longitude grid on the earth,

* take a “sample point” at every intersection point between latitude and longitude lines (done at, say, 1 degree or 5 degree intervals)

* exclude points that fell in the ocean

* calculate the great circle geographic distance between all points

* input this into a hierarchical clustering algorithm

…and you would get out a nice treelike diagram that would show each of the major continents as clusters, probably with linked continents forming groups of groups.

This would be successful hierarchical clustering, for sure, but it obviously wouldn’t be telling you about the evolutionary connectedness of the continents or anything like that. It’s a summary of the geographical distance matrix between the samples.

The interesting question is – what if you had the samples to calculate the genetic distances between the (indigenous) humans sampled at each of these points. Would you get a clustering scheme all that much different than the one you would get by clustering pure geographic distance? Probably there would be some differences, since we know that humans started in Africa and genetic diversity is highest there – but would it be a big effect? Or would the “clustering” that is observed in the genetic distances primarily just be the effect of isolation by distance and the fact that humans live on land, which is unevenly distributed around the globe? This might verify “race” in a very vague way, but it would be a long way from the traditional concepts that most people have in their head.

Lastly, we reach point 6.

6. What are the implications of these differences? Coyne writes:

Not much. There are some medical implications. […]

Here, interestingly, Templeton might actually agree, at least for the United States. Although it is illegitimate to do discrete sampling of continuous variation, and then conclude that discrete variation exists in reality, it is important to note that in some cases, “discrete sampling” in history has played a role in producing modern populations. For example, the population of the U.S. is not a random sample of the global human population. For historical reasons, in the formation of the U.S. population there really were major contributions from discrete parts of the globe – Europe, West Africa, East Asia, etc. For this reason, if you were to examine a few hundred randomly sampled Americans, you would indeed find detectable discrete genetic variation! In this (very limited) sense, “race” is physically real, but that physical reality was completely constructed by contingent cultural events in recent history!

In certain cases, this might even be medically relevant, for example if certain genotypes are common in a certain population, and these genotypes react especially well or especially poorly to a particular drug. Certainly you would want to know this if you were a doctor prescribing medication to a patient, and government agencies like the FDA will want to know it when they are approving drugs for sale or for insurance coverage. And certainly, it seems arbitrary and unfair to do drug tests on one group (say, white males) and then assume that the results will apply with equal validity to everyone else.

Finally, the fact that there is some geographical structure (whether discrete or continuous) in the human population, or in the weird sample of the human population that we have in the U.S., is important to take into account for statistical reasons. Many studies are attempting to correlate genetic traits with various diseases and conditions. But these studies can be badly misled if there is correlation in the genetic data that is due to, say, geographic ancestry that is unrecognized. This is a vast field, and pretty much represents a huge job market for evolutionary biologists and population geneticists who decades ago would have puttered around putting equations on chalkboard, but who are now crucial components of any well-done study involving genetic data from populations.

Those are some of the arguments favoring taking “race” into account in medicine and medical research. However, as you can imagine, there are all kinds of difficulties and dangers. A big one is that some statistical effect that is true in one situation – say, people who identify as African American have a higher risk of condition X – will be illegitimately extrapolated to other people who fall into doctors’ and the public’s cultural definition of African American. What if one’s ancestry is from southern Africa, but the genetic trait that correlates with the condition derives from West Africa? The statistical generalization made in some study may not apply to you.

This post is long enough, but hopefully readers can see that the topic of race in the human species is a complicated one, fraught with danger even from a purely scientific point of view, even before we get to the even more hazardous arenas of culture and politics. I think that it should be clear that one cannot give the question “Do races exist?” any kind of simple “yes” answer in humans. One can say “yes” to the question, “Is there geographical structure in human genetics?”, but hopefully I have shown that this is a long way from establishing that there is any kind of discrete genetic structure in the human population at large, i.e. discrete “racial groups” which could be identified and counted. It is possible that with ever more data, some shadow of this idea may be statistically supportable, but it seems unlikely that it will compare in strength to the strong overall pattern of continuous genetic variation following an isolation-by-distance model.

Conclusion

I’ll let the conclusion of Templeton (1998) speak for itself:

Conclusions

The genetic data are consistently and strongly informative about human races. Humans show only modest levels of differentiation among populations when compared to other large-bodied mammals, and this level of differentiation is well below the usual threshold used to identify subspecies (races) in nonhuman species. Hence, human races do not exist under the traditional concept of a subspecies as being a geographically circumscribed population showing sharp genetic differentiation. A more modem definition of race is that of a distinct evolutionary lineage within a species. The genetic evidence strongly rejects the existence of distinct evolutionary lineages within humans. The widespread representation of human “races” as branches on an intraspecific population tree is genetically indefensible and biologically misleading, even when the ancestral node is presented as being at 100,000 years ago.

Attempts to salvage the idea of human “races” as evolutionary lineages by invoking greater racial purity in the past followed by admixture events are unsuccessful and falsified by multilocus comparisons of geographical concordance and by haplotype analyses. Instead, all of the genetic evidence shows that there never was a split or separation of the “races’” or between Africans and Eurasians. Recent human evolution has been characterized by both population range expansions (with perhaps some local replacements but no global replacement within the last 100,000 years) and recurrent genetic interchange. The 100,000 years ago “divergence time” between Eurasians and Africans that is commonly found in the recent literature is really only an “effective divergence time” in sensu Nei and Roychoudhury (1974, 1982). Since no split occurred between Africans and Eurasians, it is meaningless to assign a date to an “event” that never happened. Instead, the effective divergence time measures the amount of restricted gene flow among the populations (Slatkin 1991).

Because of the extensive evidence for genetic interchange through population movements and recurrent gene flow going back at least hundreds of thousands of years ago, there is only one evolutionary lineage of humanity and there are no subspecies or races under either the traditional or phylogenetic definitions. Human evolution and population structure have been and are characterized by many locally differentiated populations coexisting at any given time, but with sufficient genetic contact to make all of humanity a single lineage sharing a common, long-term evolutionary fate.

My recommendation would be to ditch the discussion of “human races” in science wherever possible (it may be unavoidable in certain fields, e.g. medicine, due to its cultural reality), particularly in genetics, and instead go with “geographic ancestry” instead. Some of us humans will trace back to a small region somewhere, others of us will be fusions from two or five or six continents. Coyne’s post argued that races exist, but were becoming less distinct due to interbreeding. I would say that continuous geographic structure exists, but that it is becoming weaker as the human population becomes more and more panmictic.

Note: After I wrote the above, I noticed that Coyne has a followup post up that cites the famous “map of Europe reflected in genetics” (paraphrasing) figure from Novembre et al. (2008). He notes the evidence for the isolation-by-distance effect, and concludes that there are no races in Europe, at least:

In other words, genetically closer populations are more genetically similar, as expected if individuals tend to mate with other individuals from the same country, and close by. This is an “isolation by distance” model: genetic similarity falls off gradually with distance. As the authors note, this does not support the existence of “discrete, well-differentiated populations,” i.e., there are no races. None are expected in such a small area, particularly because biological “races” are those populations that (at least at one time) were geographically isolated and genetically differentiated. That geographical isolation never happened in Europe.

[…]

As I said, this doesn’t show that there are discrete “races” in Europe, and I don’t think there are obviously discrete “races” anywhere these days, though there is large-scale genetic differentiation among worldwide population suggesting that such races once existed as relatively discrete and geographically isolated populations. The discreteness that once existed, or so I think, is now blurring out as transportation and migration are beginning to mix the discrete groups into not a melting pot, but sort of a lumpy pudding of humanity.

What is clear is that, with considerable accuracy, you can diagnose an individual’s geographic origin from his genes. Nearly everyone’s DNA contains reliable information about their recent and ancient past. We are not all genetically alike. If we were, you couldn’t do studies like the one of Novembre et al. But neither are we radically different genetically, for if we were, you wouldn’t need hundreds of thousands of genes for such accurate predictions.

So Coyne is actually approaching the Templeton view of human genetic diversity pretty rapidly, although he is still buying into “relatively discrete” races at a larger scale (what are they then?), which I would disagree with.

References

Edwards, A. W. F. (2003). “Human genetic diversity: Lewontin’s fallacy.” BioEssays 25(8), 798-801.

Gagneux, P., C. Wills, U. Gerloff, D. Tautz, P. A. Morin, C. Boesch, B. Fruth, G. Hohmann, O. A. Ryder and D. S. Woodruff (1999). “Mitochondrial sequences show diverse evolutionary histories of African hominoids.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 96(9), 5077-5082.

Lewontin RC. The apportionment of human diversity. In: Dobzhansky T, Hecht MK, Steere WC, editors. Evolutionary Biology 6. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts. 1972. p 381-398.

Millstein, R. L. (2009). “Populations as Individuals.” Biological Theory 4(3), 267-273.

Templeton, A. R. (1998). “Human Races: A Genetic and Evolutionary Perspective.” American Anthropologist 100(3), 632-650.

Notes

* For example (1) he promotes a method that seems to be subjective and to not work (it’s called Nested Clade Analysis, it’s not about nested clades in the traditional phylogenetic/macroevolutionary senses of those words, and it would take awhile to explain…but see “Why does a method that fails continue to be used?” by Lacy Knowles for the basics, and Google Scholar for the ongoing discussion.) and (2) he doesn’t seem to get Bayesian methods and his one-man war against ABC (Approximate Bayesian Computation) consists primarily of misunderstandings of Bayesian logic (although ABC does have various limitations and problems, they aren’t primarily the ones he identifies; see e.g. “Invalid arguments against ABC: Reply to AR Templeton” by Csillery et al.).

However, NCA is Templeton’s pet method and was popular for a long time (thousands of citations), and Bayesian logic can be difficult even for very smart professionals, especially if they have been raised thinking of frequentism as the only way to think about statistics, and Templeton has vast experience in human population genetics and popgen applied to medicine, so I don’t think his opinions on broader, simpler issues can be dismissed because of the fight over NCA/ABC.

I might as well add that my specialty is evolutionary biogeography at the macroevolutionary level of large number of species related by a phylogeny, not phylogeography, which operates primarily at the level of population genetics of one species or a few closely-related species/populations, so my opinions in this arena are still developing as I learn more about it.

** Another note:re-reading Templeton (1998) after some time just now, I found rather more Nested Clade Analysis in there than I remembered. I don’t think this affects the parts of his conclusions that I quoted, except perhaps for his skepticism of the 100,000 year “divergence time” for Africans vs. non-Africans and his endorsement of an alternative model (derived from his “trellis model”).

Templeton in 1998 is in part lobbying for the “trellis” model, where all humans are connected by gene flow and always have been, all the way back to Homo erectus. He makes the modern isolation-by-distance observation a part of the evidence for this, but I don’t see any reason to endorse this. We could have a fairly standard Recent Out-of-Africa model (adding minor interbreeding with Neandertals etc.) and still get the isolation-by-distance effect as long as humans have the behavior of breeding with nearby tribes and thus having high gene flow but mostly with adjacent groups.

Other links of interest: