Peter H. A. Sneath (1923 - 2011)

Word has reached me that Peter Sneath died last Friday at his home in Leicestershire. He was 87 years old. For a more complete and entertaining autobiographical account see page 77 of this Bulletin of Bergeys International Society for Microbial Systematics.

Peter was a medical microbiologist, who, in the late 1950s, began to work on numerical methods for classifying bacteria. He developed numerical clustering methods. He soon came into contact with Robert Sokal, who was doing the same. Together they wrote Principles of Numerical Taxonomy, a widely-noticed textbook advocating taking a phenetic approach to classification, basing it on measures of overall similarity rather than any inference of phylogeny. The smartest thing Sokal and Sneath did was to not fight over who invented numerical taxonomy, but to join together to promote it (Sneath was first author on the 1973 revision Numerical Taxonomy).

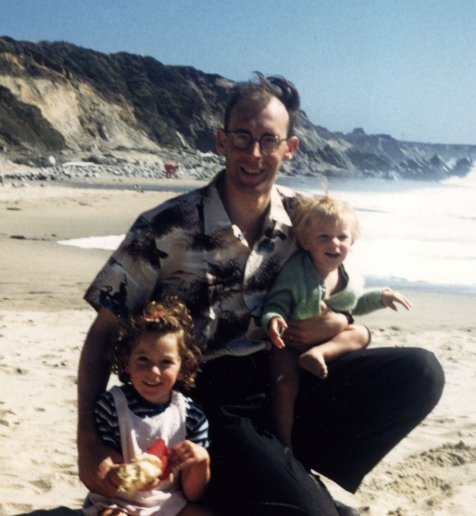

Peter Sneath with his children, about 1960. Photo by Joan Sneath, courtesy of the late Peter Sneath

Numerical taxonomy rattled the systematic establishment, then dominated by followers of Ernst Mayr and George Gaylord Simpson’s school of “evolutionary systematics”. It encouraged and stimulated many younger people to look into numerical approaches. By about 1980 phenetic approaches had been pushed aside by phylogenetic systematics, but Sneath and Sokal’s work is still regarded by mathematical clusterers as the most important founding work in their field. The most widely-used of Sneath’s methods is the UPGMA clustering method (independently also invented by F. J. Rohlf). [See comment of September 30 below for correction of this statement].

I always enjoyed meeting Peter and Joan Sneath. Peter was intrigued by any and all uses of numerical and computer methods in science, and was even willing on occasion to violate his own precepts and come up with methods for analyzing phylogenies.

He wrote a pioneering 1975 paper (with Sackin and Ambler) on detecting recombination between lineages, for example. I remember Peter telling me that as he traveled around he collected soil samples to study their bacteria. He carried no sterile vials for that – he simply went out and bought a ream of typing paper, as it was sterile, then used some to scoop up the sample and fold it into an envelope. It was a brilliant common-sense improvisation typical of the best of his generation of English scientists.