A Full Genome from Denisova, Siberia

Last week a paper was published on the DNA sequencing of the complete genome of an approximately 40,000 year old finger bone from Denisova in Southern Siberia (Reich et al. 2010). There are a number of very significant findings in the paper.

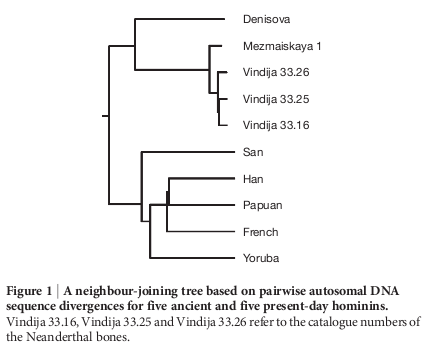

1) The results showed that the Denisova individual was more closely related to Neanderthals than to modern humans. However, the Denisovan does not fall within the range of Neanderthal variation. There are a few lines of evidence suggesting that the Denisovan and Neanderthal lineages had separate histories once they diverged and did not form a single population. The Neanderthal genomes sequenced so far have low genetic diversity, indicating that Neanderthals passed through a genetic bottleneck after splitting from the Denisovans. With only one Denisovan genome available as yet, we don’t know how diverse they were.

2) Even more spectacular was the finding that the Denisovan genome appears to have made a genetic contribution of about 4.8% (+/- 0.5%) to the genomes of living Melanesians. Interestingly, they did not contribute to the genomes of modern populations such as Han Chinese and Mongolians which live near Denisova now. The Denisovans obviously interbred with the ancestors of modern Melanesians at some point, but it seems unlikely to have happened at Denisova, which suggests that the Denisovans lived over a considerable area of eastern Asia.

This finding recalls another major discovery made earlier this year, which was that Neanderthals appear to have contributed from 1% to 4% of the genome of all living non-Africans (Green et al. 2010; Panda’s Thumb blogged about it in June). This was not expected, given that earlier mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) results showed no evidence of any genetic mixing between Neanderthals and modern humans (but did not exclude the possibility either). The new Reich et al paper has improved the precision of this estimate; they calculate that Neanderthals contributed 2.5% (+/- 0.6%) to the genome of modern non-Africans. That means that the Neanderthals and Denisovans together account for an impressive 7.5% of the ancestry of modern Melanesians.

The finger bone, by the way, is the same one that was in the news in March 2010, when another paper (Krause et al. 2010) was published on the bone’s mtDNA. The results of that paper showed that the Denisova mtDNA was more different to both humans and Neanderthals than they were to each other. The Denisova mtDNA shared a common ancestor with both humans and Neanderthals mtDNA about a million years ago, compared to about 500,000 years for the human and Neanderthal mtDNA common ancestor. This is obviously in disagreement with the new findings from the full genome, which are almost certainly correct because they are based on far more complete data. There are a couple of possible explanations for this. The mtDNA lineage may have been introduced into the Denisovan population by interbreeding with another unknown hominid lineage, or randomness due to genetic drift may have allowed a divergent mtDNA sequence to survive in the Denisovan population while being lost in the human and Neanderthal populations.

The finger bone was nicknamed the X-Woman, X for ‘unknown’ and ‘woman’ because mtDNA is maternally inherited, but in fact it didn’t necessarily belong to a female. Males have mtDNA too; they just don’t pass it on to their children. The new analysis, however, shows that the ‘X-Woman’ bone really was female - there are not nearly enough Y-chromosome genetic sequences in it for it to have belonged to a male (the handful of Y-chromosome sequences found would be from contamination).

3) A second bone found at Denisova, a second or third upper molar tooth, has also had its mtDNA sequenced. This mtDNA sequence was very similar to that of the finger bone, indicating that both individuals probably belonged to the same population.

4) The molar tooth from Denisova also gives us some intriguing hints about the anatomy of the Denisovans. It is larger than comparable teeth in both early modern humans and Neanderthals (and also Homo erectus, if it is a third molar). It also has a number of anatomical differences from Neanderthal teeth to which it would be most closely related. Obviously it would be desirable to have more Denisovan fossils and knowledge of more of their anatomy, but the tooth suggests that they are distinctive anatomically as well as genetically from both humans and Neanderthals. The 2nd and 3rd molar teeth of other hominids alive at the time such as Homo heidelbergensis and Homo erectus are not well represented in the fossil record, but the little we have also does not seem to closely resemble the Denisovan tooth.

For now, the population to which these two fossils belonged is being called ‘Denisovans’. A decision on how to classify them will probably be deferred until we know more of their anatomy. The fact that Denisovans and Neanderthals both interbred with humans does not necessarily mean they are all the one species - there are many cases of modern species able to interbreed. Animal species are more usually defined by whether they ordinarily form a single interbreeding population, rather than by whether they are merely capable of interbreeding. This is obviously a fuzzy criterion, but the fact that the Neanderthal and Denisovan contributions to the human genome appear to have been limited events means these hominids could still end up being classified as three species. (Or two. Or one.)

The evidence that the Denisovans contributed genes to modern Melanesians did not come completely out of left field. In April, a group of researchers reported evidence of humans interbreeding with other hominids in the Middle East about 60,000 years ago, and in eastern Asia about 45,000 years ago. That matched up with the discovery of Neanderthal genes in modern non-Africans, and there was speculation then that the Denisovan fossil, whose mtDNA was published around the same time, was in the right time and place to account for the 2nd interbreeding event. And so it came to pass.

Incidentally, these discoveries would seem to be the final nail in the coffin for the multiregional model. There are two competing schools of thought about the origin of modern humans. The ‘Out of Africa’ model claims that the ancestors of modern humans left Africa in the last 100,000 years, totally replacing all other hominids around the world. The multiregional model holds that humans evolved towards modern humans in synchrony throughout Africa, Europe and Asia, with genetic mixing between neighbouring populations ensuring that they did not diverge into multiple species. The Out of Africa model isn’t completely correct, but could be modified to include two episodes of genetic mixing with other hominids. The multiregional model, on the other hand, looks to be completely dead in the water.

Implications for Creationism

Young-earth creationists such as Answers in Genesis will doubtless claim that this research supports their claims that humans, Neanderthals, and other archaic hominids all form one species. However, it’s a lot harder to see how all the necessary population events can be squeezed into 10,000 years. Starting from Adam and Eve, humans apparently populated Africa, Asia and Europe, then some of them left Africa, picked up some Neanderthal genes from the Middle East, then populated the world again, with some of them picking up more genes from the Denisovans and going on to populate Melanesia. Somehow, this emigrating group was also able to cause all the other humans to become extinct. At some point a flood occurred, killing all but 8 humans and removing most of the genetic variability. It would be tempting to assume the flood took care of removing the Neanderthals and Denisovans, but that would leave the problem of explaining how their genetic contributions made it into the modern world. Supposing one person on the ark had Neanderthal genes, and another Denisovan genes. The Arkers then had children who would have married each other. How could it happen that Africa ends up with the greatest genetic diversity, and yet none of the Neanderthal and Denisovan genes are found there? Meanwhile, the Neanderthal genes managed to find their way into all non-Africans, while the Denisovan genes found their way into the Melanesian population, but nowhere else (if 8 people populate the world, how can one of those people account for 5% of the genome of 0.15% of the world’s population?). This scenario seems, to put it mildly, hopelessly improbable if not completely impossible. I await with interest a creationist population model to explain all this activity in a young-earth time frame.

See also: The Denisova Genome FAQ, by John Hawks

References

Dalton 2010: Neanderthals may have interbred with humans. Nature Online, Apr 20, 2010.

Green et al. 2010: A draft sequence of the Neanderthal genome. Science, 328:710.

Krause, Good, Viola et al. 2010: The complete mitochondrial DNA genome of an unknown hominin from southern Siberia. Nature 464:894.

Reich, Green, Kircher et al. 2010: Genetic history of an archaic hominin group from Denisova Cave in Siberia. Nature 468:1053.