Mapping fitness: bacteria, mutations, and Seattle

![]() Thinking about fitness landscapes can stimulate detailed discussion and consideration of the meanings and limitations of such metaphors, and my introductory comments did just that. Most notably, Joe Felsenstein pointed us to the various ways these depictions can be employed, and urged everyone to use caution in interpreting them. All too true, but the goal here is modest: I want to discuss the interesting questions that arise when considering the relationship between genotypes and phenotypes, i.e., how a particular genetic makeup influences fitness, whether the genetic makeup in question is simple or complex, and however fitness is conceived. These questions can take further discussion in all sorts of directions, but there are two that I have in mind in this series. First, I want to point to increasing capacity of scientists in their ability to examine these relationships experimentally. Second, I want to highlight the failure of design creationists to address or even to understand such matters.

Thinking about fitness landscapes can stimulate detailed discussion and consideration of the meanings and limitations of such metaphors, and my introductory comments did just that. Most notably, Joe Felsenstein pointed us to the various ways these depictions can be employed, and urged everyone to use caution in interpreting them. All too true, but the goal here is modest: I want to discuss the interesting questions that arise when considering the relationship between genotypes and phenotypes, i.e., how a particular genetic makeup influences fitness, whether the genetic makeup in question is simple or complex, and however fitness is conceived. These questions can take further discussion in all sorts of directions, but there are two that I have in mind in this series. First, I want to point to increasing capacity of scientists in their ability to examine these relationships experimentally. Second, I want to highlight the failure of design creationists to address or even to understand such matters.

If you know a little about evolution, you already know that mutation is a major source of genetic novelty. And you've probably heard (or surmised) that the mutation rate in a population or lineage is thought to contribute to something called "evolvability." No mutation means no evolvability. And maybe it's clear that too much mutation is a bad thing, too. And so, the mutation rate itself is a parameter that contributes to fitness, with fitness referring in this case to the ability of a population to adapt or compete over time. There can be, it seems, a fitness landscape for mutation rates, in which we could depict fitness as a function of the mutation rate. Perhaps we could even sketch such a landscape if we could generate genetic variants that differ solely in their mutation rate.

Experiments like this have been done, and the best-known examples come from work on bacteria. Earlier this year, a group at the University of Washington in Seattle, led by Lawrence Loeb, took the analysis a big step further, in work that sought "to characterize the fitness landscape across a broad range of mutation rates." The co-first authors of the report are Ern Loh and Jesse Salk.

Loh et al. introduce their work by noting that previous analyses of the influence of mutation rate on bacterial fitness were informative but limited in scope. These experiments tended to emphasize mutators (variants with higher-than-normal mutation rates) and tended to perform head-to-head competitions between only two variants (mutator vs. normal, for example). And modeling studies of the phenomena would benefit from further validation by experimental data. So the authors set out to measure bacterial fitness in the presence of widely-varying rates of mutation. Their experiment employed two innovations that filled these gaps in previous work:

The panel of variants included not two, or ten, but 66 versions of the DNA copying enzyme (DNA polymerase I). These variants all grow normally when they live alone, but they exhibit mutation rates that span six orders of magnitude, from one thousandth of the normal rate to a thousand times the normal rate. (Because the DNA polymerase is the main copying machine, its fidelity is a major determinant of the error rate and therefore the mutation rate.) This means that unlike all or most previous work in this area, their library included antimutators - variants with a lower-than-normal mutation rate.

The authors staged evolutionary competitions in which all 66 variants were put together and grown for 350 generations. Specifically, they regularly diluted the cultures so that the environment cycled between low density (leading to rapid growth) and high density (leading to nutrient depletion and stasis).

The experiment is, then, relatively simple in concept. Create a pool of variants and then see which ones (if any) will take over when they're in competition with all the others. We'll skip the details of the creation of this library of variants, though it could be fun to discuss in comments. Suffice it to say that because the variants all grow normally when living in isolation, any differences in competition outcome are likely due to the effects of mutation rate on the ability of variants to adapt in the face of competition.

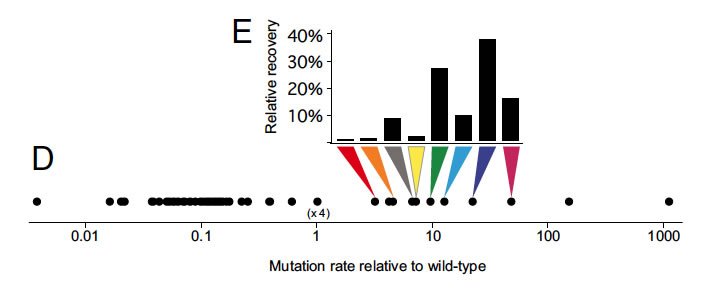

In one excellent graph (from Figure 2 of the paper) shown below, the authors summarize their basic result: in the various competitions, only eight of the 66 variants emerged as winners or co-winners. Those eight variants represent a relatively small subset of what we might call mutation-rate space. Here's how the authors describe the outcome:

The recovered mutants were all moderate mutators, with mutation rates ranging from 3- to 47-fold greater than that of the wild type. Of these, 88% had at least a 10-fold elevated mutation rate. No antimutators were detected in the output population despite constituting 77% of the input population.

You can see this from the graph: each colored arrow points to a mutation rate, representing a variant that was one of the winners, and the bar graph above it shows how often that particular variant won. The scale left to right is mutation rate. Variants from normal on down (going left on the scale), all of those antimutators, were losers. Ditto for the super-mutators at the other end of the scale.

You can see this from the graph: each colored arrow points to a mutation rate, representing a variant that was one of the winners, and the bar graph above it shows how often that particular variant won. The scale left to right is mutation rate. Variants from normal on down (going left on the scale), all of those antimutators, were losers. Ditto for the super-mutators at the other end of the scale.

Loh et al. went on to show that the winning variants had adapted by putting the winners into head-to-head competition with their ancestors. (Oh the cool things you can do when your experimental organism is E. coli!) In other words, the winning variants had evolved, becoming more "fit" than when they started, by virtue of competing in a crowded jungle of other variants. The winners were different from their ancestors, but also from each other, demonstrating that the winners had acquired new characteristics beyond their higher mutability. The authors conclude that "under conditions where organism fitness is not yet maximized for a particular environment, competitive adaptation may be facilitated by enhanced mutagenesis."

The paper is fun to read and relatively approachable. Check it out.

So back to the two points I wanted to emphasize. First, the authors briefly employ the "fitness landscape" metaphor, simply to indicate that mutation-rate variation (in this case due to engineered genetic variation in DNA polymerase I) is likely to map onto "fitness" (in this case, ability to win an evolutionary competition under a certain set of environmental conditions) in interesting and perhaps surprising ways. Their data add a layer of intriguing complexity to studies and discussions of the roles of mutation and mutability in evolution and evolvability. Second, they did their experiments at the University of Washington School of Medicine. Less than 12 miles away, in Redmond, Washington, is a research institute dedicated to intelligent design. According to Google Maps, it's a 16-minute drive from that institute to the UW School of Medicine. (Or 40 minutes in traffic. Neither of these numbers impresses me, having lived in metropolitan Boston for five years.) Now, some of the researchers at that institute are keenly interested in mutation and evolution in bacteria. Do you suppose those researchers are interacting with the Loeb lab? Attending seminars, exchanging research materials, collaborating, consulting? I would be interested to hear from scientists at either place. If, as I suspect, none of those things has happened, then maybe the folks at that institute in Redmond could, with our encouragement, expand their influence and find new opportunities by contacting their world-class colleagues, right in their own neighborhood. As curious as they claim to be about evolution and mutation, they would be crazy not to. Right?

(Cross-posted at Quintessence of Dust.)

Loh E, Salk JJ, & Loeb LA (2010). Optimization of DNA polymerase mutation rates during bacterial evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107 (3), 1154-9 PMID: 20080608