Geo-xcentricities part 2; the view from Mars.

Einstein rings, a spectacular prediction of relativity, taken from Hubble (Image credit Hubble/NASA)

Einstein rings, a spectacular prediction of relativity, taken from Hubble (Image credit Hubble/NASA)

You may remember a little while back I wrote about a conference of modern Geocentrism (Galileo was Wrong). Geocentrism is the belief that Earth is the centre of the Solar system, nay the entire Universe and everything revolves around it.

Todd Wood attended the conference, and you can read the about his growing sense of incredulity in his posts (part 1, part 2, part 3, part 4, part 5).

It turns out that these folks are relativity deniers.

Image of the crescent Earth and Moon on October 3, 2007, taken by the HiRISE instrument of the NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

Image of the crescent Earth and Moon on October 3, 2007, taken by the HiRISE instrument of the NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

Which is pretty strange, the usual tack is to argue for Geocentrism based of relativistic frame equivalence. Arguing against relativity is pretty hard, as it is one of the best confirmed theories of physics we have. From gravitational lensing (see images above) to frame dragging, relativity has passed increasingly stringent tests with flying colours.

These geocentricists apparently need relativity disconfirmed so the the Michelson-Morely experiment proves the Earth at rest.

Now there is a lot of problems with this (not the least because they need a non-moving ether to explain the M-M experiment, then a moving ether to explain Foucault’s Pendulum) and other geocentrist positions. Some of the problems can be demonstrated with intensive mathematics, some with not so much maths (like the claim that GPS doesn’t use relativistic corrections, which is untrue.)

Earth as seen from Mars taken by the Spirit rovers’ panoramic camera in 2004.

Earth as seen from Mars taken by the Spirit rovers’ panoramic camera in 2004.

However, in the spirit of my first post on this conference, where I tried to get people to do observations themselves that disproved first the Ptolemaic then the Tychonian systems, I want to get people to do something much simpler, related to observational astronomy.

Also in the spirit of Einstein, who tried to imagine what the word would look like if you were travelling on a photon, I want you to imagine your are standing on Mars.

The evening sky on Mars on April 29, 2005 as simulated by Stellarium (the location isn’t at the same latitude and longitude as opportunity, so the view is slightly different from the rover).

The evening sky on Mars on April 29, 2005 as simulated by Stellarium (the location isn’t at the same latitude and longitude as opportunity, so the view is slightly different from the rover).

What would you see from the surface of Mars that would be different in a Tychonian system (the system favoured by our modern geocentricists) versus a heliocentric system system?

As the Tychonican system is an inverted Copernican system, things like the phases of the Earth would be identical (see this JAVAscript model, advance the time to October 3, 2007 to match the image of crescent Earth and Moon above, and flip between the Tychonian and Heliocentric models to see what I mean).

Earth imaged by the panoramic camera of Opportunity an hour after Sunset on April 29, 2005 (Image Credit NASA/JPL).

Earth imaged by the panoramic camera of Opportunity an hour after Sunset on April 29, 2005 (Image Credit NASA/JPL).

There is a big difference that would be immediately apparent. Whether in the Tychonian or Heliocentric systems, from the point of view from Mars, Earth would appear to be a morning or evening star that appeared to revolve around the Sun.

However, the geocentricists are using a geostationary model, where the 24 hour day is produced by the Sun rotating about the Earth. So in a period of 24 hours, an observer on Mars (armed with an occultation disk) would see Earth rise from the sun, then fall back, then reappear on the other side of the sun and repeat the process again.

During the period that the Mars rovers took images of the Earth, at maximum elongation Earth was 42-47 degrees from the Sun as seen from Mars. For the Earth to move from maximum elongation to inferior or superior conjunction (at least, as it would appear from Mars, because in the Tychonian system Earth can’t have conjunctions) takes 6 hours (in a 24 hour day there will be four 6 hour segments as the Earth goes out, comes back, goes out and comes back again from the solar disk).

So the Earth will appear to move 42 degrees (taking the lowest figure) in 6 hours, or 7 degrees per hour against the background stars (approximately, it’s slightly more complicated than this, but rough figures are all we need). That’s 14 Lunar diameters per hour! Earth is fairly hooting along compared to the background stars. In one minute Earth would move 1/4 of a Lunar diameter which is quite noticeable.

Now look at the image above. It is a composite of 3 x 15 second images taken with the panoramic camera, you can see the image of Earth is slightly elongated. However, remember that Mars rotates, and any 15 second exposure will cause slight star trailing due to its rotation. The trail we see of Earth is nothing like what we would expect if it was moving to a 24 hour rhythm, as it hares along the sky (roughly 1/5th of a Lunar diameter). Still, for confirmation we have to check Earth’s movement against that of the background stars.

Fortunately, in the original image there is a background star just above Earth (it’s best seen in the TIF file). It has the same degree of elongation that the Earth does. This falsifies the Tychonian system, thus the solar system is heliocentric.

So “Eppur si muove” because it um, doesn’t move (with respect to the background stars as seen from Mars).

Image credit; Topper, D. Galileo, Sunspots, and the Motions of the Earth: Redux Isis, Vol. 90, No. 4 (Dec., 1999), pp. 757-767

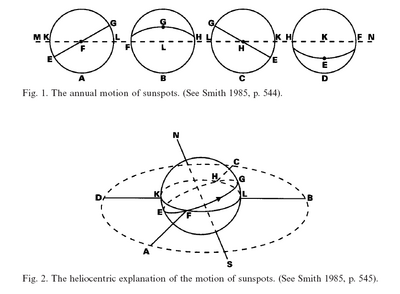

Illustration of the annual variation in the paths sunspots take across the sun, and the heliocentric projection which explains it.

Image credit; Topper, D. Galileo, Sunspots, and the Motions of the Earth: Redux Isis, Vol. 90, No. 4 (Dec., 1999), pp. 757-767

Illustration of the annual variation in the paths sunspots take across the sun, and the heliocentric projection which explains it.

The account of sunspot movement that Galileo provides in the Third Day of the Dialogue is easily explained with reference to Figure 1. Let continuous line MN represent the plane of the ecliptic, while EFG, FGH, GHE, and HEF represent projected paths for the sunspots at tri- monthly intervals A, B, C, and D-that is, in one annual circuit along the ecliptic. Viewed at position A, therefore, the sunspots appear to ascend in a straight line from E toward G. At B they seem to describe an upward curve from F through G toward H, whereas at C they appear to descend along a rectilinear path from G toward E. Finally, at D they seem to follow a downward curve from H through E toward F.

Given these general observations, Galileo was able to deduce the basic solar model illustrated in Figure 2, where DABC-the plane of the ecliptic-cuts the solar globe at great circle KFLH. NS, meanwhile, is the axis about which the sun makes a complete spin roughly once a month. So EFGH is the solar equator, along which the direction of motion is counterclockwise from E toward G. The apparent path the sunspots follow at any point in the year is accordingly determined by how the sun’s equator would look from any point on the ecliptic. From A, for instance, it would be seen straight on, as represented by A in Figure 1, whereas from B it would appear as it does in B in Figure 1, and so on. Hence the root cause of these appearances is the tilt of the solar axis with respect to the ecliptic Drake, Galileo Studies, pp. 180, 198 n 17 as quoted in Topper