No Longer Sleeping in Seattle

Note: Another guest post from Don Prothero. I have added links, and the references section, where I put some graphics so that readers can see what Prothero is describing. – Nick Matzke

Update: Shermer’s review is now online here, and the audio of the debate is here.

I guess my interview with National Geographic News online last week, and last Monday’s debate with Stephen Meyer and Richard Sternberg must have really wounded them, because this week I’m the new bete noire of the IDists over at the Discovery Institute. For two years, they completely ignored my 2007 book, Evolution: What the fossils say and why it matters even though it pulled no punches in criticizing them, has been on the best-seller list for most of that time, and greatly outsells Meyer’s new book. (Incidentally, they bragged at the debate about how his book had won an award from the Times Literary Supplement. This is false. It turns out that there was a favorable review by Thomas Nagel, a maverick philosopher of morality, not an award by the TLS. My book, on the other hand, DID win the Outstanding Book in Earth Science Award for 2007 from the American Association of Publishers).

In any case, they’ve been attacking me with everything they have this week, with Casey Luskin and Jonathan Wells both weighing in. Normally, it is not worth dignifying their garbage with a response, but in case any of the readers of Pandasthumb.org want to get the straight facts (and not their distorted version), here’s what you should know:

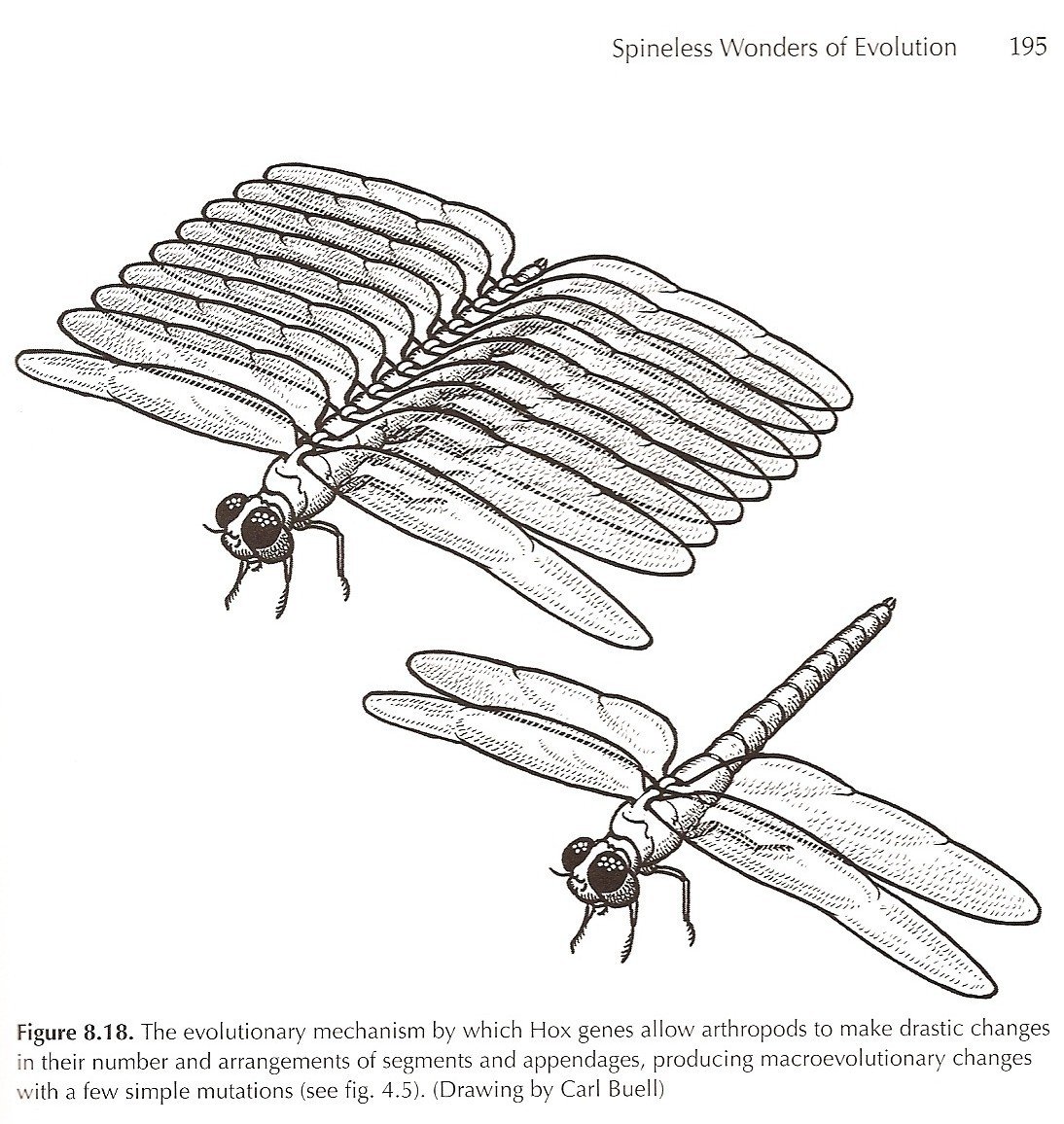

1. Multi-winged insects and Hox genes: when evo-devo came up in Monday’s debate, Meyer and Sternberg began arguing with each other about reconstructions of a 12-winged dragonfly that I had published in my book. They tried to get a laugh by claiming that such a bug has never been found. As usual, they completely missed the point of that illustration, and failed to read any of the explanation or discussion in the caption or text. The text clearly points out that the 12-winged dragonfly is a thought experiment, an illustration to show that a simple change in Hox genes allows the arthropods, with their modular body plan of adjustable numbers of segments and interchangeable appendages on each, to make huge evolutionary changes by simple modifications of regulatory genes. This is the aspect of evo/devo that should answer structuralist Sternberg’s objections to Neo-Darwinism, if he only bothered to comprehend it, and solves much of the question over how macroevolutionary changes take place. And it’s not as far-fetched as they tried to make it sound. Homeotic mutant flies with four wings are well documented [known since the early 1900s – NM], and fossil insects with more than two pairs of wings are common as well (Kukalova-Peck, 1978; Raff, 1996).

In a related matter, the post by Wells completely screws up its discussion of four-winged flies. Apparently, he didn’t read the book very carefully either, because it is a well known fact in developmental biology circles that the halteres, the tiny knob-like organs behind the single pair of wings in Diptera, are simply modified wings that now function as balancing organs. The 4-winged homeotic mutants have changed the Hox mutation so that they atavistically recover the ancestral 4-winged insect condition, and never develop halteres. Apparently Wells doesn’t realize that halteres ARE the developmental equivalent of the second pair of wings.

Finally, in the debate, Sternberg and Meyer also mocked the significance of the antennipedia mutation, showing their complete lack of understanding of its significance. This mutation of the Hox genes that control appendage development causes legs to grow on the head of fruit flies where antennae should grow. This is not favorable to the fly, of course (as Meyer and Sternberg mockingly point out), but they missed the point entirely: the antennipaedia mutation demonstrates that arthropod appendages (legs, wings, halteres, pincers, mouthparts, antennae, etc.) are all modular and interchangeable, so a simple Hox mutation can rapidly transform an arthropod with one set of appendages into one with a different set, and make a macroevolutionary change with minimal point mutations required.

2. “Cambrian explosion”: during the debate I pinned down Meyer with one of the blatant lies that creationists often spout: there are supposedly no “transitional fossils” before the “Cambrian explosion.” I put up direct quotes from Meyer et al. (2003) and Meyer (2004) to that effect, then showed the incredibly diversity of pre-trilobite fossils from the Precambrian, from the prokaryotes 3.5 b.y. ago, to the Doushantuo fossils of China (600 m.y. ago) which include embryos of sponges, cnidarians, and several bilaterian groups (Chen et al. 2009), to the multicellular soft-bodied Ediacaran fauna (580-550 m.y. ago), which are clearly large (some over a meter in size) but possess no skeletonized tissues, to the “little shellies” of the first two stages of the Cambrian, which include clear examples of primitive mollusks, sponges, cnidarians, and other groups, but are minimally skeletonized. Only during the third stage of the Cambrian, the Atdabanian (520 m.y. ago) do we see abundantly skeletonized fossils like trilobites. With this preservational advantage of calcified skeletons, the diversity of fossils known begins to increase (mostly in a lot more species of trilobites). The origin of the early members of the major invertebrate phyla is spread between the Precambrian Doushantuo and the Cambrian Atdabanian, spanning 80 million years. Hardly an explosion! I prefer to use the term “Cambrian slow fuse” because that’s how modern paleontologists and biologists understand the data that is now available – but the creationists keep on using the outdated term “Cambrian explosion” because it suits their purposes.

Caught in his lies, Meyer then tried to redefine what he meant by “Cambrian explosion” in 2003 and 2004 to mean ONLY the Atdabanian Stage, and argue about how there are no fossils with complex eyes and other structures before that time. If he actually had any relevant training in paleontology (he has no degree in paleontology or biology, yet insists on writing about the topic without the proper credentials), or if he even bothered to see the outcrops and collect them for himself (I have), he would understand the true situation. Unlike the Middle Cambrian, when we have extraordinarily well preserved fossils like those of the Burgess Shale in Canada, or the Chengxiang fossil in China, we have no similar locality with extraordinary preservation during the first two stages of the Cambrian. If we did, we might see a soft-bodied pre-trilobite arthropod with the precursor of the compound eye, as well as other transitional fossils. The apparent “explosion” that Meyer finds inexplicable is really an issue of preservation (a hit-or-miss proposition we cannot control) plus whatever environmental thresholds that were finally exceeded when the Atdabanian Stage began (most paleontologists and geochemists think it was the amount of oxygen needed to calcify large skeletons). It’s an interesting problem on which hundreds of paleontologists and geologists are actively working and arguing about different hypotheses that might explain it, but certainly no mystery that requires divine intervention.

And the Discovery Institute further shows their inability to keep up with current scientific thinking when they attacked the problem on their site this week. All that Luskin could muster was two or three quotes out of context from almost 20 years ago, long before the Doushantuo and “little shelly” faunas were discovered and fully documented. Since they have no one properly trained in paleontology who actually knows something about fossils, they resort to the quote-mining tactics of the old-fashioned creationists instead.

None of these issues are scientific problems, only problems with creationists who cannot read or comprehend the basic science, or simply don’t want to understand what they read. Judging by how “intelligent design” has faded from media attention since their huge loss in the Dover decision in 2005, and is no longer being pushed on school districts (they try the “teach the controversy” or “balanced treatment” approaches now), the Disco gang is becoming less and less relevant. But if you happen to get in an argument with them, you should know the truth. Meanwhile, we’ll probably see the DI site get bored of attacking me, and back to pushing religious dogmas, attacking global warming, gay rights, stem-cell research, and other extreme right-wing causes that they are so fond of.

References and a few notes [added by NM]

Kukalova-Peck, Jarmila. (1978). Origin and evolution of insect wings and their relation to metamorphosis, as documented by the fossil record. Journal of Morphology, 156: 53-125. doi: 10.1002/jmor.105156010

Raff, Rudolf A. (1998). The Shape of Life: Genes, Development, and the Evolution of Animal Form, University Of Chicago Press, 1-544. Pages 404-417 discuss the evolution of insect wings.

Note: This is the figure from Prothero’s book under discussion:

90%-plus of the hundreds of other figures in Prothero’s book are of transitional fossils – but nevertheless Wells feels entitled to accuse Prothero of fraud. Says Wells: “Need evidence for Darwinian evolution? Just make it up. That’s the lesson of Donald Prothero’s book, Evolution: What the Fossils Say and Why It Matters.”

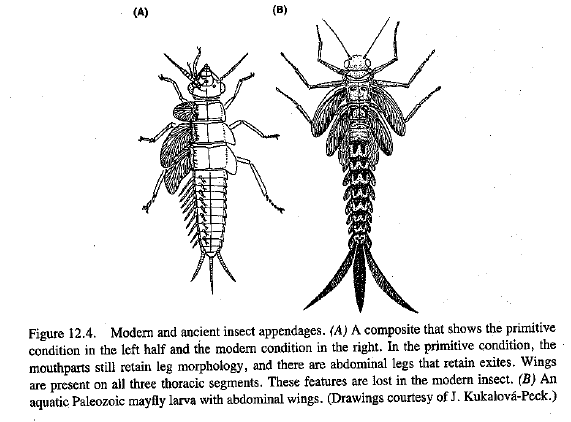

Looking at the references mentioned above tells a different story than Wells. E.g., Figure 12.4, p. 409 of Raff 1998 shows us one of the (incredible!) ancient fossil insects with many pairs of wings (see Kukalova-Peck 1978 for more detailed drawings and references). (By the way, various fossils, and some modern examples, are known of insects showing a third pair of winglike structures, in front of the regular two pairs.)

Kukalova-Peck’s (1978) original caption (Figure 28, Plate 7, p. 110) for the Paleozoic insect reads:

Typical Paleozoic mayfly, older nymph. Wings were curved backwards, articulated, and probably used for underwater rowing; prothoracic winglets were fused with protergum. Abdomen was equipped with nine pairs of veined wings. Legs were long, cursorial, with five tarsal segments. Protereismatidae; Lower Permian, Oklahoma. After Kukalova (‘68). Original reconstruction from a complete specimen.

A 1985 publication by Kukalova-Peck (Figure 31, p. 946) gives this fossil the description: “Kukalova americana Demoulin, 1970, older nymph”, if people want to look it up.

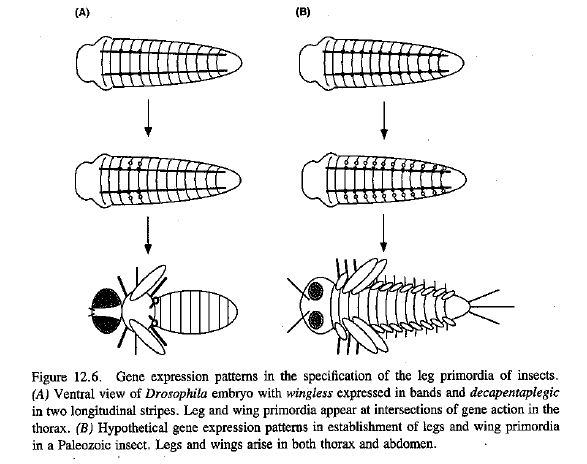

Figure 12.6 and p. 412 of Raff (1998) gives a more detailed version of the argument made briefly in Prothero (2007):

See also e.g. Figure 29 of Kirschner et al. 2005.

Cambrian

Chen, J.-Y., Bottjer, D.J., Li, G., Hadfield, M.G., Gao, F., Cameron, A.R., Zhang, C.-Y., Xian, D.-C., Tafforeau, P., Liao, X., and Yin. Z.-J.

- Complex embryos displaying bilaterian characters from Precambrian Doushantuo phosphate deposits, Weng’an, Guizhou, China. PNAS v. 105, no. 45, pp. 19056-19060. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904805106

For a good diagram of the various events and time periods in the late Precambrian and early Cambrian, see Figure 1, p. 358 of: Marshall, Charles R. (2006). Explaining the Cambrian “Explosion” of Animals. 34: 355-384. doi: 10.1146/annurev.earth.33.031504.103001

Small version below:

Figure 1 Complex anatomy of the Cambrian “explosion.” Dates from Grotzinger et al. (1995), Landing et al. (1998), Gradstein et al. (2004), and Condon et al. (2005). Neoproterozoic carbonate carbon isotope curve from Condon et al. (2005), Early Cambrian curve largely from Maloof et al. (2005) but also from Kirschvink & Raub (2003), and Middle and Late Cambrian from Montanez et al. (2000). Note the wide range of values in part of the Early Cambrian; this is partly due to geographic variation, but also to variation measured in Morocco. Disparity from Bowring et al. (1993). Diversity based on tabulation by Foote (2003) derived from Sepkoski’s compendium of marine genera (Sepkoski 1997, 2002); all taxa found in the interval, as well as those that range through the interval, are counted. Short-term idiosyncrasies in the rock record can add noise to diversity curves, so to dampen that effect, taxa found in just one interval can be omitted (singletons omitted). Note that standing diversities were much lower than the values shown; many of the taxa found in a stratigraphic interval did not coexist. The boundary crosser curve (M. Foote, personal communication) gives the number of taxa that must have coexisted at the points shown; however, because traditional stratigraphic boundaries are based on times of unusual taxonomic turnover, these estimates may underestimate typical standing diversities.