Does Science Lead to Atheism?

No.

That was the short answer. The longer answer is that scientists are more likely to disbelieve in God than are nonscientists, and eminent scientists are more apt to be disbelievers than journeyman scientists. But does science lead them to atheism? Possibly, but it seems more likely that freethinkers or skeptics are attracted to science than that science creates atheists.

I studied this question a few years ago, when John Lynch and I prepared an article for the New Encyclopedia of Unbelief. What follows the horizontal rule is an excerpt from that article. One of the conclusions we drew was that biologists, anthropologists, and psychologists were more likely to disbelieve in God than physical scientists and engineers. That conclusion has recently been called into question, and I will discuss the new data after the second horizontal rule.

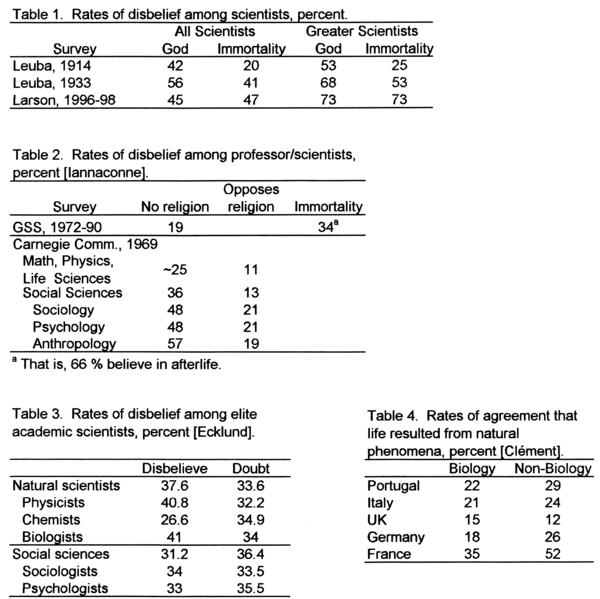

Measuring Unbelief among Scientists (1914 and 1933). … the psychologist James H. Leuba surveyed a large number of US scientists in order to learn their beliefs about God and immortality. In both polls, disbelievers (not including doubters or agnostics) represented a plurality over believers and doubters (Table 1). Further, the least likely to be believers were psychologists, followed by sociologists, biologists, and physicists, in that order. The order stood firm across the years. Distinguished scientists (as identified by American Men of Science) exhibited a substantially greater rate of disbelief than “lesser” scientists.

Leuba’s poll was, however, not without problems. First, because the U. S. was almost monolithically Christian, Leuba formulated two questions that asked, in essence, whether respondents believed in a particular Christian conception of God. Asking his questions in that way militated against getting positive responses from, for example, pantheists such as Robert Millikan and Albert Einstein, who associated God with the universe and its laws and thus did not revere, in Leuba’s words, “the God of our Churches.” Leuba asked respondents whether they believed in “a God to whom one may pray in the expectation of receiving an answer” (a question specifically defined to exclude psychological or subjective consequences of prayer), disbelieved in such a God, or had no definite belief. Second, several questionnaires were returned with remarks intended to justify the respondents’ refusals to answer the questions. According to Leuba, most of these were from disbelievers; hence, he concluded, the percentage of disbelievers may have been understated in his poll.

Scientists are more educated than the general population, and Leuba, a religious humanist, thought that increasing education would decrease rates of belief in God. To test his hypothesis, he surveyed college students at two unidentified colleges: a high-ranking college that was divided among the major Protestant denominations, and a college that was “radical” in its leanings. In both colleges, the number of believers in both God and immortality decreased with age or academic advancement (freshman through senior years). Leuba also cites a decrease in belief at one of the colleges between 1914 and 1933, as well as similar results found at Syracuse University in 1926. Leuba, a professor at Bryn Mawr College outside Philadelphia, does not identify the two colleges in his study, but they are probably in the northeast, if not the Philadelphia area. If the major Protestant denominations means the mainline Protestant churches, then Leuba’s studies of college students may not be representative, inasmuch as they omit students affiliated with churches not heavily represented in the northeast. Oddly, Leuba does not mention the Roman Catholic Church.

Measuring Unbelief among Scientists (the 1990’s). In 1996 and 1998, Edward J. Larson and Larry Witham replicated Leuba’s surveys. For consistency, they did not edit Leuba’s questions, despite the cultural changes that had occurred in 80 years. Additionally, American Men and Women of Science no longer highlights eminent scientists, so Larson and Witham derived their “greater” scientists from the membership of the National Academy of Sciences; comparison with Leuba’s “greater” scientists is therefore problematic, because the NAS probably contains substantially more-eminent scientists than the highlighted scientists of the earlier surveys.

Larson and Witham found that nearly 50 percent of the scientists and nearly 75 percent of the “greater” scientists surveyed disbelieve in both God and immortality. An additional 15-20 percent are doubters. It is hard to make much of three numbers, but during the century the percentage of disbelievers increased monotonically in every category, except for a peak in the percent of scientists who disbelieved in 1933. Disbelief in immortality more than doubled among scientists in general and nearly tripled among “greater” scientists. It is thus hard to credit Larson and Witham’s claim that belief among scientists has remained more or less steady for 80 years.

C. Mackenzie Brown has analyzed Leuba’s data and also suggested that demographics may make comparison between Leuba’s and Larson and Witham’s surveys difficult. For example, more scientists now are women, and women are more likely to be religious than men. This factor reduces the number of disbelievers in the later surveys and possibly disconfirms Larson and Witham’s conclusion that scientists’ religious beliefs have not changed much since 1914. Brown has similarly noted that applied scientists are underrepresented among the greater scientists and adds drily that their underrepresentation may be relevant to any discussion of the beliefs of eminent scientists.

In 1998, Laurence Iannaconne and his colleagues examined existing data gathered between 1972 and 1990, and tried to assess the prevalence of scientists’ belief in God. They found that 19 percent of “professors/scientists” have “no religion” and 11 to 21 percent “oppose religion” (Table 2). It is hard to compare these figures with those of Leuba and Larson, but arguably between 27 and 40 percent of professors/scientists may be doubters or disbelievers. The study broke the data down further by discipline and found a hierarchy similar to that found by Leuba: Social scientists, at 36 percent, were most likely to have no religion, followed by physical scientists and mathematicians (27 percent) and life scientists (25 percent). Among the social scientists, sociologists (35 percent), psychologists (48 percent), and anthropologists (57 percent) were most likely to have no religion. According to a 2003 Harris poll, by contrast, 90 percent of all adults [in the U.S.] believe in God and 84 percent in survival of the soul after death; that is, 10 percent disbelieve in God or are doubters, and 16 percent disbelieve in immortality or are doubters.

Interpreting the Data. Leuba speculated whether scientists become disbelievers or whether independent thinkers willing to confront reigning orthodoxies become scientists. The greater scientists are presumably on average more-independent thinkers than the lesser; the fact could account for the increase of disbelief among greater scientists. That conclusion is supported by a study by Fred Thalheimer, who concluded that religious beliefs are frequently set during high school or college and that nonreligious students may choose more-intellectual or -theoretical endeavors.

Scientists who study biology, psychology, and sociology and anthropology are more likely to disbelieve in God and immortality than physical and applied scientists. Leuba speculated that physicists and engineers see a creator in the lawfulness of the physical and engineering worlds. Social and biological scientists may be less likely to see lawfulness in their studies, and Brown asks, further, whether social and biological scientists are perhaps influenced by the suffering that they see and physical scientists do not see. Thus, the question may be why biological and social scientists are more likely to disbelieve, rather than why physical scientists and engineers are less likely. Arguably, then, science leads to disbelief, at least among those already inclined to be independent thinkers.

Leuba predicted that increasing scientific knowledge would lead to increasing disbelief. That prediction is apparently (at least partly) correct. He further predicted that the religions would adapt to the best scientific insights and “replace their specific method of seeking the welfare of humanity by appeal to, and reliance upon divine Beings, by methods free from a discredited supernaturalism.” That prediction, at least so far, is largely incorrect.

Measuring Unbelief among Scientists (2004-2007). Elaine Ecklund and Christopher Scheitle have recently examined the religious beliefs of scientists as a function of discipline. They discuss a survey of faculty at 21 elite research universities. Among the questions they asked were, “Which one of the following statements comes closest to expressing what you believe about God?” The statements ranged from “I have no doubts about God’s existence” through “I have some doubts, but I believe in God” to “I do not know…and there is no way to find out” and “I do not believe in God.” To compare their results with Leuba’s and others, I identified “I do not believe in God” with disbelief and identified “I believe in God sometimes” and “I do not know…and there is no way to find out” with doubt. The comparison is problematic, if only because Leuba’s survey concerned a God who potentially answers prayers. The results are presented in Table 3. They support the conclusion that scientists are more apt to be disbelievers than the general public, but they are at odds with the conclusion that the rate of disbelief correlates with discipline. Ecklund and Scheitle, however, performed a statistical analysis that suggests nevertheless that biologists may be somewhat less inclined toward religion than physicists; they speculate that the correlation, if it is real, may result from what they call the contentious relationship between evolution and certain religious groups.

Ecklund and Scheitle’s study is marred somewhat both by its restriction to elite scientists and by its mechanism for choosing those elite scientists. Not every faculty member at an elite university is an elite scientist, certainly not on a par with members of the National Academy of Sciences. Nevertheless, they found that the best predictor of their scientists’ religious practice is the scientists’ childhood religious practice and conclude, more or less in agreement with Thalheimer, that freethinkers or doubters to some extent self-select when they become scientists. Thus, science may not lead to disbelief; rather, disbelievers or skeptics are led to science.

Finally, Ecklund and Scheitle found that younger scientists are more apt to be religious than are older scientists and note without comment that this finding “could indicate an overall shift in attitudes towards religion among those in the academy.”

Unbelief outside the US. I do not know of any studies similar to Leuba’s outside the United States. Europe is generally thought to be less religious than the United States, but Andrew Curry, writing in Science, notes some disquieting appearances of creationism in Europe. He cites a German study, which I have not read, to the effect that students’ openness to creationism is less a result of religion than of their failure to appreciate or understand science.

Pierre Clément and his colleagues report on a study of the creationist beliefs of teachers, as opposed to professors and practicing scientists. The cohort of “teachers” comprises both practicing teachers and students studying to become teachers. The study included 19 countries, mostly from Europe, the Levant, and northern Africa. Approximately one-third of the teachers were biology teachers, and the remainder taught the national language. Among 14 of those countries, 12.5 % of respondents were agnostic. In France and Estonia, more than 50 % were agnostic. The authors give no indication whether the biology teachers were more or less likely to be agnostic than the language teachers.

The study asked questions such as, “Which of the following four statements do you agree with most? … 1. It is certain that the origin of the humankind results from evolutionary processes.

- Human origin can be explained by evolutionary processes without considering the hypothesis that God created humankind. 3. Human origin can be explained by evolutionary processes that are governed by God. 4. It is certain that God created humankind.” A similar set of questions asked about the origin of life, as opposed to the origin of humanity. The questions were translated into each national language.

Clément and colleagues considered those who ticked question 4 to be (anti-evolutionist) creationists, whereas those who ticked question 3 were designated creationist-evolutionists - most probably what in the United States are called theistic evolutionists. Only about 2 % of the respondents from France, for example, were creationists; more than 80 % of respondents from Morocco and Algeria were creationists, even among biology teachers. Creationism was more likely in those who were more religious, either in belief or in observance, irrespective of religion. Those who said that the theory of evolution contradicted their own beliefs ranged from a few percent among agnostics, through approximately 25 % among Catholics and Protestants, and 40 % among Orthodox, to nearly 75 % among Muslims. Acceptance of evolution, including theistic evolution, among the entire cohort of teachers, however, increased with years of training, from about 45 % among those with less than 2 years of training through 80 % among those with 4 or more years of training. These numbers are all rough, because I had to pick most of them off some fairly small graphs. I suspect that the correlation with religion is partly the result of demographics; the study did not compare, for example, Catholics and Muslims within a single country, such as France.

The study included five countries in western Europe: France, Germany, the United Kingdom, Portugal, and Italy. Approximately 10 % of biology teachers in the UK and 15% in Portugal responded that it was certain that God created life - the response that Clément and his colleagues consider the creationist response. Nearly 20 % of the language teachers in Italy responded similarly.

On the other hand, roughly 15 % of biology teachers in the UK and Germany, a bit over 20 % in Portugal and Italy, and 35 % in France responded that the origin of life resulted from natural processes (Table 3). The language teachers’ responses to the same question ranged from a low of perhaps 12 % in the UK (which at 35 % also had a relatively high fraction of theistic evolutionists) to 52 % in France. In four of the five countries, the percentage of language teachers who thought that life had resulted from natural processes exceeded the percentage of biology teachers; I haven’t the foggiest idea why.

Finally, the percentage of both biology and language teachers who ticked natural causes or theistic evolution was least in the Muslim and Orthodox countries, Lebanon, Malta, and Poland.

Conclusion. Paul Strode and I tried to show that science is not necessarily incompatible with religion, though it certainly falsifies the specific claims of some religions. Nevertheless, both atheists and creationists (some of them, anyway) want to think that science necessarily leads toward atheism or agnosticism. It is hard to say, but it seems more likely that skeptics or freethinkers, who may be already inclined toward disbelief in God, are more likely to become scientists or, perhaps, science teachers. The claim that social scientists are less likely to believe than are physical scientists may not stand up to scrutiny.

References.

Anonymous, “Harris Poll: The Religious and Other Beliefs of Americans 2003,” Skeptical Inquirer, July-August, 2003, p. 5.

Brown, C. Mackenzie, “The Conflict between Religion and Science in Light of the Patterns of Religious Beliefs among Scientists,” Zygon 38(3): 603-632 (September), 2003.

Clément, Pierre, and Marie-Pierre Quessada, “Les convictions créationnistes et/ou évolutionnistes d’enseignants de biologie: une étude comparative dans dix-neuf pays,” Natures Sciences Sociétés 16, 154-158, 2008; in French.

Clément, Pierre, Marie-Pierre Quessada, Charline Laurent, and Graça Carvalho, “Science and Religion: Evolutionism and Creationism in Education: A Survey of Teachers’ Conceptions in 14 Countries,” XIII IOSTE Symposium, Izmir, Turkey, The Use of Science and Technology Education for Peace and Sustainable Development, 21-26 September 2008.

Curry, Andrew, “Creationist Beliefs Persist in Europe,” Science 323: 1159, 2009.

Ecklund, Elaine Howard, and Christopher P. Scheitle, “Religion among Academic Scientists: Distinctions, Disciplines, and Demographics,” Social Problems, 54(2): 289-307, 2007.

Iannaconne, Laurence, Rodney Stark, and Roger Finke, “Rationality and the ‘Religious Mind’,” Economic Inquiry 36(3): 373-389, 1998.

Larson, Edward J., and Larry Witham, “Scientists Are Still Keeping the Faith,” Nature 386: 435-436, 1997.

–, “Leading Scientists Still Reject God,” Nature 394: 313, 1998.

–, “Scientists and Religion in America,” Scientific American 281(3): 89-93 (September), 1999.

Leuba, James H., Belief in God and Immortality, Boston: Sherman, French, 1916.

–, “Religious Beliefs of American Scientists,” Harper’s Monthly Magazine, August: 291-300 1934.

Thalheimer, Fred, “Religiosity and Secularization in the Academic Professions,” Sociology of Education 46: 183-202 (spring), 1973.

Young, Matt, and John Lynch, “Unbelief among Scientists,” New Encyclopedia of Unbelief, Amherst, N.Y.: Prometheus, 2007, pp. 687-690.

Young, Matt, and Paul Strode, Why Evolution Works (and Creationism Fails), New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers, 2009, chap. 18.