Dembski Weasels Out

Over at uncommon descent William Dembski is musing over Richard Dawkins Weasel program. Why you may ask? Way back in prehistory (the 1980’s) Dawkins wrote a little BASIC program (in Apple BASIC of all things) to demonstrate the difference between random mutation and random mutation with selection, which many people were having trouble grasping. Now, this wasn’t a simulation of natural selection, and Dawkins was very careful to point this out.

But as a demonstration of selection versus simple random mutation, with the string “methinks it is a weasel” being selected in a matter of minutes, when simple random mutation would take longer than the age of the Universe, it was pretty stunning. As a result, creationists have been having conniption fits over this little program for decades. Such is its power, the Issac Newton of Information Theory, William Dembski, spent a not inconsiderable portion of his time attacking this toy program. In particular, he claimed that after every successful mutation, the successful mutation was locked into place, and couldn’t be reversed. But he was wrong, and it seems he just can’t admit it.

As you can see, by using the Courier font, one can read up from the target sequence METHINKS*IT*IS*LIKE*A*WEASEL, as it were column by column, over each letter of the target sequence. From this it’s clear that once the right letter in the target sequence is latched on to, it locks on and never changes. In other words, in these examples of Dawkins’ WEASEL program as given in his book THE BLIND WATCHMAKER, it never happens (as far as we can tell) that some intermediate sequences achieves the corresponding letter in the target sequence, then loses it, and in the end regains it.

However, it is very easy to understand from the description of the program in the Blind Watchmaker, that no locking is occurring. The list Dawkins presents is not all of the strings that are generated per “generation”, just the “fittest” strings (ie, just those closest to the target. Showing all 6,400 strings in a paperback book is just not feasible, nor useful[1]). And even then, Dawkins is only showing every 10th fittest string! So even if the best string was backing and forthing, you are very likely to miss it (and don’t forget the back mutations to less fit strings will be selected against, and not show up when we are only displaying the best string). It doesn’t take a mathematical genius to work this out.

People have been telling Dembski this for years (Wesley Elsberry for one, and again recently), but he just hasn’t listened. Now there is documentary evidence that Dembski is wrong, from a documentary on Dawkins work. How does Dembski handle this?

Interestingly, when Dawkins did his 1987 BBC Horizons takeoff on his book, he ran the program in front of the film camera: www.youtube.com/watch?v=5sUQIpFajsg (go to 6:15) There you see that his WEASEL program does a proximity search without locking (letters in the target sequence appear, disappear, and then reappear). That leads one to wonder whether the WEASEL program, as Dawkins had programmed and described it in his book, is the same as in the BBC Horizons documentary.

Don’t admit you were wrong, claim a different program is used (ignoring for the fact that the weasel program in the documentary still converged on the correct solution in a matter of minutes). However, it is easy to see from the video that all of the generated strings are being displayed, not just every 10th fittest as was in the book. That’s the difference between printed media and things like TV, you can easily show the intermediate steps without causing confusion, again, imaging if Dawkins had shown all 6,400 intermediates, that would be roughly 160 pages of gibberish[1] to demonstrate something anyone with an IQ above room temperature could figure out from themselves.

In any case, our chief programmer at the Evolutionary Informatics Lab (www.evoinfo.org) is expanding our WEASEL WARE software to model both these possibilities. Stay tuned.

Say what? How long does it take someone to write a program that basically takes a string, copies it with mutations, compares it to a target, chooses the best mutant, copies and mutates the new string, and compares again until the target is reached? When I first read Dawkins book I made my first weasel program in a couple of hours in GBASIC (as did almost every geek in the Universe), converting it to QBASIC and using arrays and stuff took an afternoon, because I was trying to be fancy with the arrays, and adding in a lot of comments so people could follow what I had done. So a real programmer should have been able to make a “non-locking” version in the time it took Dembski to write his blog post. Heck, Dembski could have done it himself. People have written versions of the weasel program in Matlab[3], and Dembski is supposed to be a mathematician, why didn’t he?

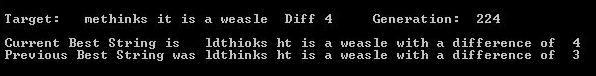

Indeed, if he were lazy he could have just looked one up on the web and checked how it was programmed. For a time there was a cottage industry in making weasel programs, and there were lots of them. To demonstrate, I have resurrected a program I made in QBASIC[4]. Now, the program I’ve written [4] is written to be as close as possible to Dawkins original as described in the book in terms of how it works (although I’ve added in the ability to change the string and the number of offspring). All offspring strings are mutated (one mutation per string, the mutation is a random letter placed in a random lcocation), and no mutation is “locked” into place. Any given “good” mutation can potentially be mutated out again (and is if you watch carefully). If you run the program with 100 offspring (as per Dawkins), unless you are preternaturally fast you won’t see any backing and froing. If you run the program with 50 or 30 offspring, it is easier to see backing up [2]. The screen shot below shows the current best string, which is worse than the previous best string (and I had to add wait loops so it was slow enough for me to catch with PrintScreen, see also the string capture listed at [2] at the bottom of the post).

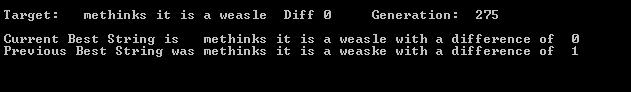

Even with the low offspring number the program converges on a solution (see second screen shot).

This demonstrates that Dawkins program works just fine without “locking”. With populations of 100 offspring, where it is hard to see back mutation, I got convergence in 65, 36 and 100 generations in 3 separate runs. Quite similar to the runs Dawkins reports in his book.

The question is, instead of constructing conspiracy theories about how Dawkins must have changed his program (rather than realising the difference between showing all of a screen dump on an interactive medium like TV, and showing the most fit strings from each generation in a printed book is one of presentation, not core programming), why didn’t Dembski write his own program (or get his minions to write one for him) to check for himself before spinning wild theories?

Oh. I forgot. That’s the difference between Intelligent Design and real science; real science actually tests hypotheses with data.

[1] If he has 100 offspring per generation, than a run of 64 generations will generate 6,400 individual strings. Typical books can have 40 lines to a page, hence 160 pages to show all offspring, as well as as the fittest of each generation.

[2] Here are runs I did using my program, with the program dumping only the fittest strings to file.

Off spring size 100, showing 10 individual generations (convergence in 37 Generations)

Best string ; Generation

pewjhokr ju hs c wecule ; 20

pewjhokr ju hs c wecsle ; 21

pewjhokr ju hs a wecsle ; 22

petjhokr ju hs a wecsle ; 23

metjhokr ju hs a wecsle ; 24

metjhokr ju hs a weasle ; 25

metjhokr ju is a weasle ; 26

metihokr ju is a weasle ; 27

metihoks ju is a weasle ; 28

metihmks ju is a weasle ; 29

metihmks ju is a weasle ; 30

Hmm, that looks “locked in” doesn’t it BUUUT here’s what happens with a population size of 50. Remember, nothing else has been changed about the program except the population size. Convergence is in 187 generations, in previous runs I have had convergence in 73, 98 and 128 runs).

Best string ; Generation

lethinks jt is a weasle ; 135

lethinks jt is a weaske ; 136

lethinks jt is a weaske ; 137

lethinks jt is a weatke ; 138

lethinks jt is a weatke ; 139

lethinks jt is a weatke ; 140

lethinks jt is a weatke ; 141

lethinks jt is a weatke ; 142

lethinks ju is a weatke ; 143

lethinks ju is a weatke ; 144

lethinks gu is a weatke ; 145

Note we see reversion now, despite the program being unchanged. If we had just looked at generation 130 and 140 (every 10th generation, as Dawkins shows in order to conserve space in his book) we would have seen

lethinks jt is a xeasle ; 130

lethinks jt is a weatke ; 140

Which Dembski imagines is locking, but its not.

[3] Heck, you could even do this in Microsoft Excel (shudder)

[4] My weasle program in QBASIC can be found here. Here’s the relevant section of the code

Start:

CLS

LOCATE 5, 2: PRINT “Target:”; TAB(12); Target$; “ Diff”; BestDiff; “ Generation: “; Gen

LOCATE 7, 2: PRINT “Current Best String is “; Test$(BestFit); “ with a difference of “; BestDiff

LOCATE 8, 2: PRINT “Previous Best String was “; Parent$; “ with a difference of “; CurrBestDiff

Wait10

Gen = Gen + 1

‘Find the closest (ie fittest) string

‘Note, there is NO locking

CurrBestDiff = BestDiff

Parent$ = Test$(BestFit)

‘Create Offspring, all offspring are mutants

‘no site is preserved, contrary to claims by Dembski

FOR I = 1 TO OffSpring

Site = (RND * TargLen) + 1

IF Site > TargLen THEN Site = TargLen

Char$ = CHR$((INT(RND * 26) + 96))

IF Char$ = CHR$(96) THEN Char$ = CHR$(32)

Test$(I) = Parent$

MID$(Test$(I), Site) = Char$

NEXT

UPDATE:I’ve run a freely mutating version of the weasel against a “locking version”, I report the results here.