The Rise of Human Chromosome 2: The Dicentric Problem

This essay is the first of a series authored by Dave Wisker, a Graduate Student in Molecular Ecology at the University of Central Missouri.

Back in 2005, Casey Luskin wrote an article criticizing Kenneth Miller’s testimony at the Dover ID trial called “And the Miller Told His Tale: Ken Miller’s Cold (Chromosomal) Fusion”. Luskin took Miller to task for showing that the chromosomal fusion which resulted in human chromosome 2 was evidence for the common ancestry between humans and the great apes. His argument was ably taken apart by PZ Myers here and Mike Dunford here.

Luskin also wrote:

In other words, Miller has to explain why a random chromosomal fusion event which, in our experience ultimately results in offspring with genetic diseases, didn’t result in a genetic disease and was thus advantageous enough to get fixed into the entire population of our ancestors. Given the lack of empirical evidence that random chromosomal fusion events are not disadvantageous, perhaps the presence of a chromosomal fusion event is not good evidence for a Neo-Darwinian history for humans.

Both Myers and Dunford pointed out those heterozygotes for the type of chromosomal fusion in question did not necessarily have to suffer from genetic disease or infertility. But they did not discuss the plausibility of the fixation of the fusion in the human population. In a series of forthcoming essays I will examine this, and also address some other common ID/creationist ‘problems’ with the fusion not mentioned by Luskin. The first problem is:

The Dicentric Problem

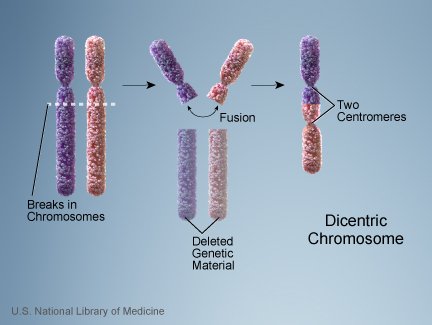

ID proponents on human chromosome 2 sometimes bring up the fact that a telomeric fusion results in a dicentric chromosome, that is, a chromosome with two centromeres. The following illustration of a similar kind of fusion shows how a dicentric chromosome can come about:

Since the centromere is the point at which the spindle attaches to the chromosome at mitosis and meiosis, wouldn’t having two centromeres result in the possibility of the spindle attaching at two points on the chromosome, pulling it apart? A common counterargument to this is that in many dicentrics, one centromere becomes inactivated, and, indeed, that seems to be the case in human chromosome 2. But doesn’t that mean we now need two mutations–first the fusion, then the centromere inactivation– to get a viable chromosome? Doesn’t that dramatically reduce the probability of the fusion becoming fixed?

Not necessarily. For a long time it was assumed all centromeres were pretty much alike, so it was also assumed that they were equally efficient at assembling kinetochores (the actual attachment point for the spindle). A 1994 paper by Beth Sullivan and her lab at Duke University suggests that not all centromeres are equal: centromeres from non-homologous chromosomes appear to assemble kinetochores at different rates. Thus, in a fusion between two non-homologous chromosomes, like that of human chromosome 2, one centromere begins preparing its kinetochores before the other, and by being able to do so may interfere with the other finishing (or even beginning) in time for the next phase of meiosis or mitosis. As the paper says in the abstract (my emphasis):

Approximately 90% of human Robertsonian translocations occur between nonhomologous acrocentric chromosomes, producing dicentric elements which are stable in meiosis and mitosis, implying that one centromere is functionally inactivated or suppressed. To determine if this suppression is random, centromeric activity in 48 human dicentric Robertsonian translocations was assigned by assessment of the primary constrictions using dual color fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). Preferential activity/constriction of one centromere was observed in all except three different rearrangements. The activity is meiotically stable since intrafamilial consistency of a preferentially active centromere existed in members of six families. These results support evidence for nonrandom centromeric activity in humans and, more importantly, suggest a functional hierarchy in Robertsonian translocations with the chromosome 14 centromere most often active and the chromosome 15 centromere least often active

By essentially ‘out-competing’ the other centromere, normal segregation of the chromosomes at meiosis is achieved, without requiring two mutations.

Reference:

Sullivan BA, DJ Wolff, and S Schwartz (1994). Analysis of centromeric activity in Robertsonian translocations: implications for a functional acrocentric hierarchy. Chromosoma 103(7):459-67