Dmanisi fossils -- more transitional than ever

The site of Dmanisi in the Republic of Georgia has produced four superb hominid skulls ranging in size from 600 cm3 to 780 cm3. These sizes range from the lower end of Homo erectus downwards into the Homo habilis range. The fossils contain a mixture of anatomical features from erectus and habilis. They could arguably be considered to belong either to primitive H. erectus (or H. ergaster), or to a new species, Homo georgicus. Vekua et al 2002 concluded:

The Dmanisi hominids are among the most primitive individuals so far attributed to H. erectus or to any species that is indisputably Homo, and it can be argued that this population is closely related to Homo habilis (sensu stricto) as known from Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, Koobi Fora in northern Kenya, and possibly Hadar in Ethiopia.

These skulls are intermediate in both anatomy and size between Homo erectus and H. habilis, and as a result are exceedingly difficult for creationists to classify. Creationists therefore either ignored them (the usual reaction), or were forced into the absurdity of claiming that the biggest skull is human but the smallest two are apes (Lubenow 2004), or the almost equally implausible suggestion that all of them are human (Line 2005).

In 2007, further light was thrown on the Dmanisi hominids with the announcement that a substantial number of bones from below the skull had been discovered (Lordkipanidze et al 2007). These included a right femur, tibia and kneecap (the most complete known lower limb of early Homo); an ankle bone, part of a shoulder blade, three collar bones, three upper arm bones, five vertebrae, and a few other small bones. Some of these bones were associated with some of the previously discovered skulls.

Analysis of the bones shows that the Dmanisi hominids definitely walked bipedally and upright. However, the bones show a number of differences from modern humans and have some features associated with Homo habilis. The upper body differences lead the authors to suggest, with some caution, that “the Dmanisi hominins would have had a more australopith-like than human-like upper limb morphology”.

Their final conclusion was:

Lordkipanidze et al 2007 wrote:

The following preliminary conclusions can be drawn: the morphology of the upper and lower limbs from Dmanisi exhibits a mosaic of traits reflecting both selection for improved terrestrial locomotor performance and the retention of primitive characters absent in later hominins. The length and morphology of the hindlimb is essentially modern, and the presence of an adducted hallux and plantar arch indicate that the salient aspects of performance in the leg and foot, such as biomechanical efficiency during long-range walking and energy storage/return during running, were equivalent to modern humans. However, plesiomorphic features such as a more medial orientation of the foot, absence of humeral torsion, small body size and low encephalization quotient suggest that the Dmanisi hominins are postcranially largely comparable to earliest Homo (cf. H. habilis). Hence, the first hominin species currently known from outside Africa did not possess the full suite of derived locomotor traits apparent in African H. erectus and later hominins.

To sum up, these new bones just make the Dmanisi hominids look more transitional than ever. They were clearly most of the way towards modern human posture and locomotion, but weren’t completely there yet:

Gibbons 2007 wrote:

The bones are so primitive that a few researchers aren’t even sure they are members of Homo. “They are truly transitional forms that are neither archaic hominins nor unambiguous members of our own genus,” says paleoanthropologist Bernard Wood…

One creationist who has discussed the Dmanisi postcranial fossils is Casey Luskin of the Discovery Institute, in a web article Human Origins Update: Harvard Scientist and New York Times Reporter Get the “Plug Evolution Memo”…Sort of. (Luskin’s article was addressed at the time by blog articles by Mike Dunford and Afarensis.)

Luskin concludes that the upper body and skull of the Dmanisi fossils are very apelike and that any claim for transitional status rests only upon the supposed humanness of the legs, so he goes to work to discredit that claim:

Luskin wrote:

Yet these leg and foot bones in many respects resemble modern apes as much as they resemble modern humans. I cannot be faulted for being skeptical of the claim that these species were necessarily evolving towards modern humans.

So what are these supposed respects in which the bones resemble apes as much as humans? Here are two of them:

Luskin wrote:

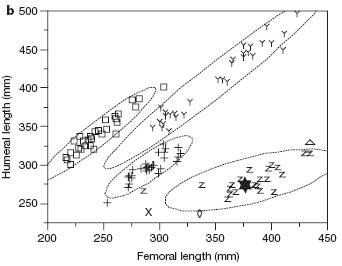

According to the Figure 3 in the Nature report, the femoral length is like that of a human or a gorilla (Fig. 3b). … Figure 3 also reports the length of an arm bone, as the humeral length resembles that of a human or perhaps a chimp (Fig. 3b).

These statements are correct as far as they go, but that isn’t very far. Figure 3b was a graph which compared femoral length with humeral length for a number of fossils and species. This particular comparison distinguishes humans from chimps from gorillas from orangs very effectively. Guess what - the Dmanisi fossil falls smack in the middle of the human range:

It’s quite clear from this graph that the humeral and femoral lengths together strongly support the claim that the Dmanisi leg bones are humanlike. To claim that these measurements are as much evidence of apelike characteristics as humanlike ones is blatantly dishonest.

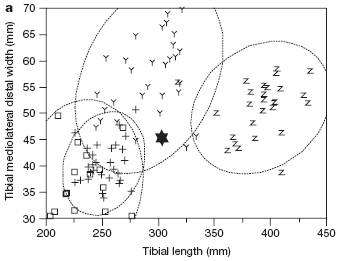

Another graph, figure 3c, which compares femoral length with tibial length, also shows the Dmanisi fossil in the middle of the human cluster. However, it is also in the middle of the gorilla cluster. This comparison doesn’t differentiate humans from gorillas, but it’s quite clear from the size and anatomy of Dmanisi that it’s nothing like a gorilla, and figure 3c does clearly differentiate Dmanisi from chimps and orangs, both of which are more comparable to it in size. So on balance, this graph also shows Dmanisi to be more humanlike than apelike.

The third graph, figure 3a, compares the tibial length with a tibial width (the tibial mediolateral distal width, to be precise). This time, there is an apelike characteristic: the tibial width could match just about anything (humans, chimps, gorillas or orangs), but the tibial length is too short for a human, matches a gorilla, and is too long for chimps or orangs. But wait a minute - wasn’t tibial length also measured in graph 3c? So it was, and there it fell in the human range, so how can it fall outside of it now? It turns out figure 3a is erroneous - Table 1 on the previous page says that human tibial lengths range from 290 to 374 mm, but that’s not the range shown in figure 3a. So, the one attribute from these graphs that did look unambiguously apelike rather than humanlike turns out to be a mistake. And, for once, it’s not even Luskin’s fault.

Luskin made another mistake when he said that the tibial width matched that of a bonobo. Luskin appears to think that the Pongo pygmaeus referred to in the graphs is the bonobo. Might I suggest that people who don’t know that Pongo pygmaeus is the formal name for the orang-utan should probably not be trying to critique scientific papers on human evolution?

Luskin’s claim that the foot bones resemble modern apes as much as modern humans is also a misrepresentation. Lordkipanidze et al 2007 has a long paragraph on the foot bones which mentions only one minor apelike characteristic, the angle of a groove for a tendon which is “slightly oblique” compared to the “more vertical orientation” of humans.

But Luskin’s counting of ape vs. human characteristics mentioned in the paper would be of little value even if he had not misrepresented them. The shape, or morphology, of bones is far more complex than can be conveyed by a few lengths. And we know that the leg bones of the Dmanisi hominids are overall very humanlike, because Lordkipanidze et al tell us so very plainly in their conclusion:

Lordkipanidze et al 2007 wrote:

The length and morphology of the hindlimb is essentially modern, and the presence of an adducted hallux and plantar arch indicate that the salient aspects of performance in the leg and foot, such as biomechanical efficiency during long-range walking and energy storage/return durring running, were equivalent to modern humans.

That’s confirmed by leading paleoanthropologist Erik Trinkaus, quoted by National Geographic:

What is clear is that the overall anatomy is primarily for walking on the ground.

There are a few other reasons why Luskin’s insinuation that the Dmanisi hominids are apes won’t fly. Although Luskin dismisses the skulls by saying only that they are small, hence like habilis, hence apelike, the skulls have many similarities with those of Homo erectus, enough to have been originally allocated to that species (Vekua et al 2002). The smallest Dmanisi skull is indeed very small (600 cm3), but the biggest one, at 780 cm3, is larger than any ape, and much larger than any ape of comparable size. The Dmanisi hominids also made stone tools (Gabunia et al 2000). So if these are apes, as Luskin wishes to imply, they are apes that walked bipedally, made tools, and had skulls very similar in both size and shape to Homo erectus. That sure makes them transitional in my book!

Luskin has one final attack to make against the Dmanisi hominids:

Luskin wrote:

Finally, according to the currently reported data, these new fossils can’t be transitional between the Australopithecines and the genus Homo. The new fossil finds were dated at 1.77 million years. Yet Homo erectus itself has been dated at 1.9 million years of age, a point conceded by Lieberman’s article. Thus, it is impossible that these fossils themselves were actually transitional between the Australopithecines and Homo erectus. (bold in original)

It is true that the Dmanisi fossils are a little younger than the oldest H. erectus fossils, but that only means those particular individuals can’t be the ancestor of the older erectus fossils. It doesn’t mean that they aren’t anatomically transitional, and it doesn’t mean that earlier members of their population couldn’t be ancestral to H. erectus. The Dmanisi hominids didn’t live at only a single point in space and time. They mostly likely existed for hundreds of thousands of years.

The first half of Luskin’s article isn’t specifically about Dmanisi. In it, Luskin compares quotes from commentators and tries to whip up imagined contradictions into a half-serious fantasy about how scientists are supposedly sending each other memos about plugging evolution to the public. Here is one of the pieces of evidence Luskin provides to support his conspiracy theories. Read it and laugh:

Luskin wrote:

NY Times’ reporter John Noble Wilford’s reversal in rhetoric is even more striking. Keep in mind that he originally reported that “Other paleontologists and experts in human evolution said the discovery [an earlier one] strongly suggested that the early transition from more apelike to more humanlike ancestors was still poorly understood.” But consider the highly different tune sung by his most recent article: “Other paleoanthropologists said the discovery could lead to breakthroughs in the critical evolutionary period in which some members of Australopithecus, the genus made famous by the Lucy skeleton, made the transition to Homo.” Apparently last month, “other paleontologists” said human evolution was “poorly understood” and now the “other paleontologists” are finding “breakthroughs in the critical evolutionary period.” What a difference a month makes! I think Wilford got the memo.

So, because “other paleontologists” said that human evolution was poorly understood (actually they didn’t, if you read carefully), and a month later “other paleontologists” (not necessarily the same ones) talked about “finding breakthroughs” (again, they didn’t, if you read carefully) we’re supposed to be impressed? This is just delusional. There is nothing remotely contradictory about saying that a new discovery might provide new information about something that is currently not well understood. Nor are either of Wilford’s statements “rhetoric”; they’re factual reporting of non-sensational statements from experts. “rhetoric” far better describes Luskin’s writing, which distorts everything it touches.

When scientists say things like “the early transition from apes to humans is poorly understood”, that might mean that we don’t know over what area the transition happened, when and at what speed it happened, the order of anatomical changes, the range of variation throughout the process, and the causes of the transition. Even superb fossils like Dmanisi can only illuminate one point in a complex process. Saying that something is “poorly understood” is not a crushing admission about the lack of evidence for evolution, it’s just being honest - hominid fossils between 2 and 3 million years ago are especially rare, and we really don’t know a lot about what was going on then.

What we do know is that the Dmanisi hominids lived 1.8 million years ago, that they looked very transitional, and that creationists can’t handle them.

References

Gabunia L., Vekua A., Swisher C.C., III, Ferring R., Justus A., Nioradze M. et al. (2000): Earliest Pleistocene hominid cranial remains from Dmanisi, Republic of Georgia: taxonomy, geological setting, and age. Science, 288:1019-25.

Gibbons, A. (2007): A new body of evidence fleshes out Homo erectus. Science, 317:1664.

Lieberman D.E. (2007): Homing in on early Homo. Nature 449:291-292.

Line, P.: Fossil evidence for alleged apemen, Technical Journal 19(1):22-42, 2005.

Lordkipanidze, D., Jashashvili, T., Vekua, A., Ponce de Leon, M. S., Zollikofer, C. P., Rightmire, G. P. et al. (2007): Postcranial evidence from early Homo from Dmanisi, Georgia. Nature, 449:305-310.

Lubenow M.L.: Bones of contention (2nd edition): a creationist assessment of human fossils, Grand Rapids,MI:Baker Books, 2004.

Vekua A., Lordkipanidze D., Rightmire G.P., Agusti J., Ferring R., Maisuradze G. et al. (2002): A new skull of early Homo from Dmanisi, Georgia. Science, 297:85-9.