One person's junk is another's treasure

In previous essays (here and here), we learned that genes encoding new proteins can and do, often, arise de novo in the course of evolution, contradicting one of the central tenets of ID proponents. The means by which these genes arise are many. One of these, suggested by Cai at al. (the subject of one of the earlier essays), involved the adaptation of a gene encoding an evolutionarily-conserved non-coding RNA via the appearance, by mutation, of appropriate translation initiation and termination (“start” and “stop”) codons. This mechanism represents an intersection of sorts between the subject of protein evolution and another matter of discussion on these blogs, namely the existence, evolution, and “function” of junk DNA. In this essay, I review a 2007 study by Debrah Thompson and Roy Parker (“Cytoplasmic decay of intergenic transcripts in Saccharomyces cerevisiae”, Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 92-101) that adds a great deal of clarity to this mode of gene and protein evolution.

To begin this review, it helps to refresh our memories with respect to a previous essay. In this essay, we learned of a class of RNAs in Saccharomyces cerevisiae that were termed “cryptic unstable transcripts” (or CUTs). These RNAs were uncovered by analysis of mutants defective in the functioning of the nuclear exosome, a complex responsible for the degradation of RNA; they were typified as transcripts whose abundances were dramatically increased by mutational disruption of the nuclear exosome. Thompson and Parker extended the study of CUTs by studying the contributions of other degrading mechanisms to the production and accumulation of CUTs. The basic strategy of the study was similar to earlier ones – compare and assess the levels of CUTs in yeast strains that carry mutations that affect other RNA degrading processes. In addition to the nuclear exosome, these processes include the decapping (1) of mRNAs in the cytoplasm, degradation of the mRNA from the 5’ end by the Xrn1 exonuclease, and nonsense-mediated decay (2) of mRNAs (abbreviated hereafter as NMD).

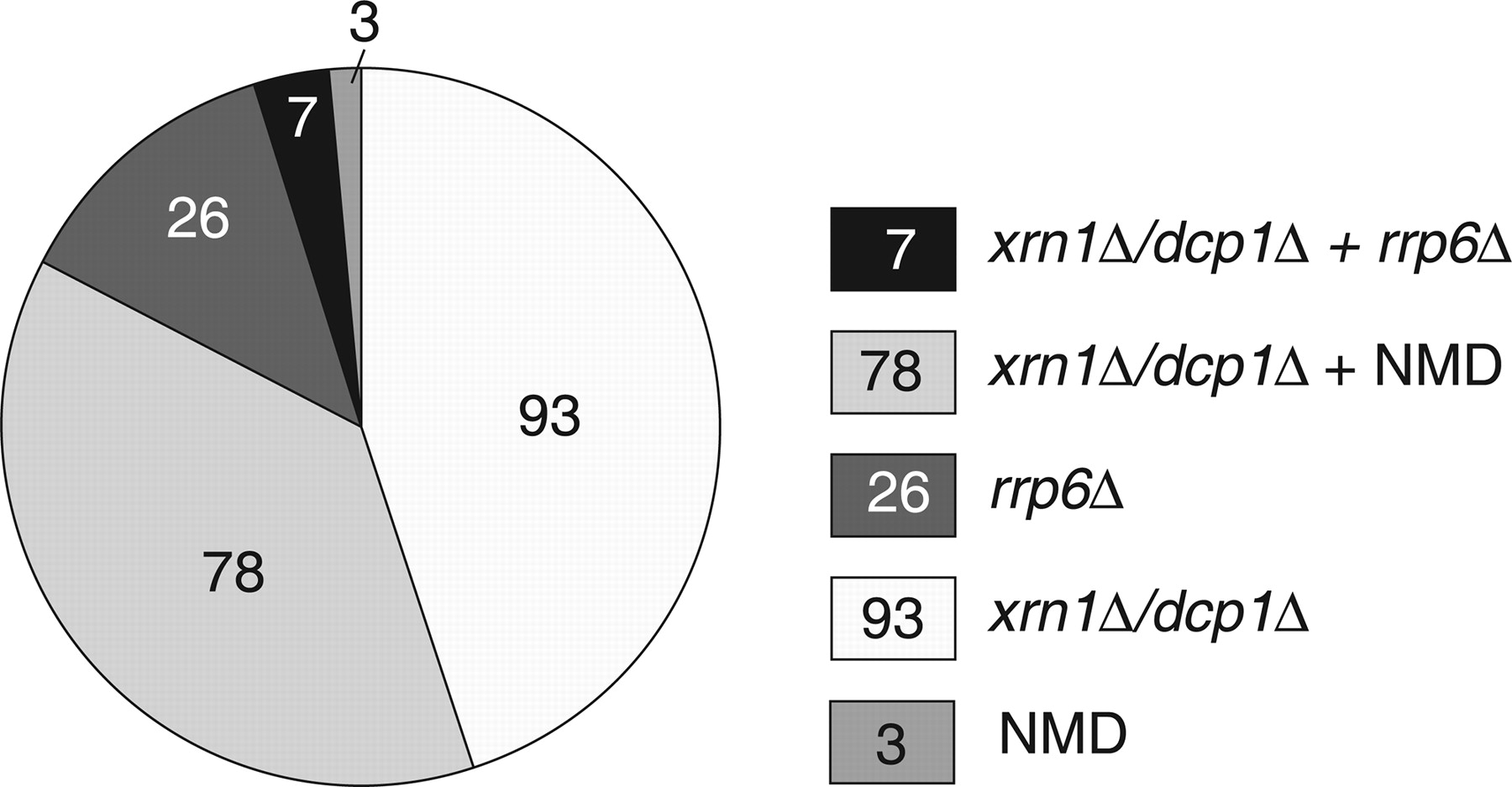

One outcome of the experiments described by Thompson and Parker was the identification of a number of subclasses of CUTs (see the following figure, which is Fig. 4 from Thompson and Parker). Thus, some CUTS had the characteristic that their steady-state levels were increased by mutation of the nuclear exosome, but not components of the cytoplasmic RNA degradation and NMD systems. This is consistent with earlier studies; however, the proportion of CUTs that fell into this class was small (13% of those studied). A much larger number (83%) were affected by mutations in the cytoplasmic RNA turnover complexes, including many (40%) that were affected by mutations in the NMD machinery. These results are important, as they indicate that a majority of CUTs are available for degradation in the cytoplasm as well as in the nucleus.

(In this figure, the nuclear exosome is “queried” by the rrp6 mutation, and cytoplasmic turnover by the dcp1 and xrn1 mutations; NMD is self-explanatory.)

The effects of mutations in the NMD complex are significant for yet another reason. NMD not only occurs in the cytoplasm, it also requires that the target RNAs be able to be translated. This is an unexpected property of CUTs, as they do not possess long open reading frames (a defining property of most translated mRNAs). Accordingly, Thompson and Parker studied the association of CUTs with polyribosomes (3). The results were clear – CUTs in fact may be found in polyribosomes, indicating that they can be “translated” by the translation machinery. (The results of this study are in Fig. 6 of the paper by Thompson and Parker.)

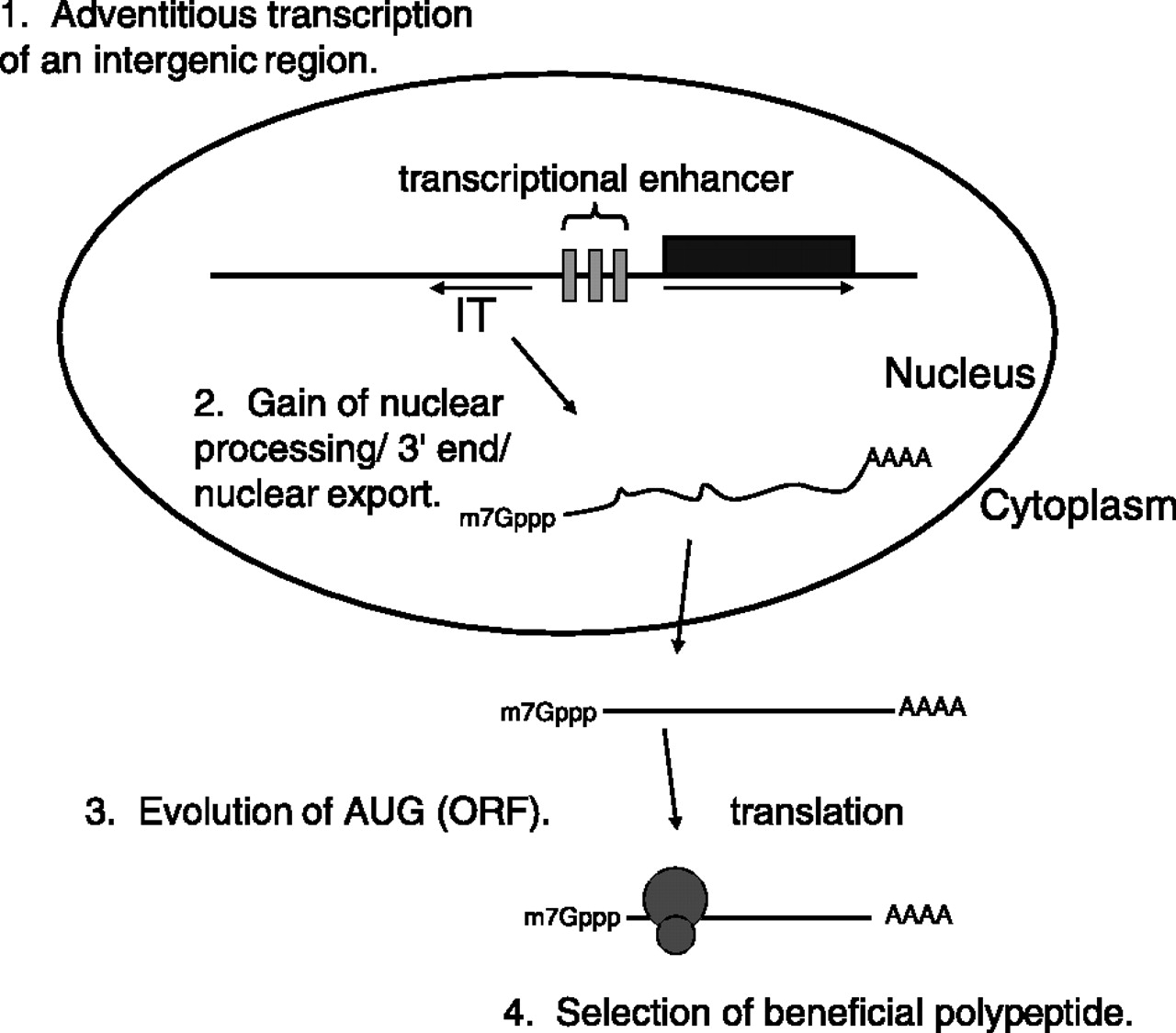

These experiments reveal an unexpected diversity in the mechanisms of mRNA quality control in the cell. However, they also provide an interesting snapshot into the path by which “junk” RNA may evolve into a moiety that encodes a functional protein (such as BSC4). This pathway is described in Fig. 7 of the paper by Thompson and Parker (see below). As the authors put it:

The ability of “noncoding” intergenic transcripts to enter translation suggests a possible mechanism whereby new ORFs encoded by bona fide mRNAs might arise (Fig. 7). First, a noncoding intergenic transcript would be produced by RNA Pol II. Note that in many cases fortuitous intergenic transcription might arise simply due to the bidirectional nature of eukaryotic transcriptional enhancers. For example, NEL025c lies head to head with the gene DLD3. Between them are two palindromic transcription factor binding sites, which mediate a response to available nitrogen sources (6, 23). We have shown that NEL025c levels respond to nitrogen source in a manner similar to that of DLD3 (data not shown) (23). Second, these intergenic transcripts would gain a 3’ end, either by normal polyadenylation or potentially by other methods for 3’-end generation. Not only would intergenic transcripts that gained a normal poly(A) tail be good substrates for nuclear export, but once exported, the capped and adenylated RNA would be expected to engage the cytoplasmic translation machinery. Intergenic transcripts producing an advantageous polypeptide would then be subjected to natural selection, allowing further evolution into a bona fide mRNA with a functional ORF. Thus, intergenic transcripts may not simply be genomic noise but may also be a factor of adaptive mechanisms requiring variation and selection, thus providing fodder for the evolution of new ORFs.”

Importantly, none of these steps is a necessarily “high-information” one (to adopt the terminology of ID proponents), but rather are well within the reach of random mutation and natural selection.

To summarize, this study adds yet another set of data to the collection that shows how readily new genes may arise. It also brings together some different areas (protein evolution, mRNA turnover) in a most interesting and provocative manner.

Citation:

Thompson, D.M., Parker, R. (2007). Cytoplasmic Decay of Intergenic Transcripts in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Molecular and Cellular Biology, 27(1), 92-101. DOI: 10.1128/MCB.01023-06

Footnotes:

-

As explained here and here, eukaryotic mRNAs possess a distinctive chemical structure at their 5’-ends that is called the cap. This cap must be removed before the mRNA can be degraded from its 5’ end by 5’->3’ exonucleases.

-

One of the quality control mechanisms that operate to reduce the contributions of errors to the goings-on of the cell involves the recognition and degradation of mRNAs that possess premature stop codons (also commonly known as nonsense codons, as they arise by the mutational conversion of codons that specify amino acids with one of the three stop codons). Truncated proteins encoded by mRNAs with premature stop codons are disposed to possess undesirable characteristics, such as being unfolded or capable of non-productively interacting with other proteins in a cell. NMD reduces these contributions, and thus helps to counter the effects of mutation and misincorporation during transcription.

-

Polyribosomes are complexes that consist of mRNAs and their associated translating ribosomes; they are termed “polyribosomes” because more than one ribosome is associated with each mRNA. They can be isolated and characterized by density gradient centrifugation.

-

This essay may also be found here.