How stupid do they think we are?

Jonathan Wells has an article at Evolution News and Views which is, typically for Wells, chock full of misinformation. But, as almost anyone could refute his central contentions with one minute on Wikipedia, you have to wonder just how stupid the Discovery Institute and its Fellows think we are.

What has Wells exercised is a report in Science Daily about a team French Scientists that have investigated the three dimensional structure of an enzyme called aminoglycoside acetyltransferase Ib (Maurice et al., 2008). They discovered that aminoglycoside acetyltransferase Ib has a flexible active site which can evolve to accommodate new antibiotics, allowing the bacteria to break these antibiotics down and make them inactive. Most excitingly, they have discovered how this enzyme can evolve to act on synthetic antibiotics that are structurally unrelated to their current substrates.

Wells is appalled by the idea that evolutionary biologists might claim some degree of responsibility for this finding, and bends over backwards to demonstrate that evolution has nothing to do with it. However, he completely misrepresents evolution, molecular biology, genetics and history. The bizarre thing is that many of the claims can be disproved with a few moments on Wikipedia.

Wells wrote:

First, some bacteria happen to have a very complex enzyme (acetyltransferase), the origin of which Darwinism hasn’t really explained. Come to think of it, most cases of antibiotic resistance (including resistance to penicillin) involve complex enzymes, and the only “explanations” for them put forward by Darwinists are untestable just-so stories about imaginary mutations over unimaginable time scales.

Aminoglycoside acetyltransferase isn’t particularly complex, it’s a simple 201 amino acid long protein that is a member of a large family of proteins that transfer acetate from Acetyl Coenzyme A to … well, just about anything. For example, many bacteria use these things for adding acetate to biogenic amines such as serotonin (yes, bacteria have serotonin). In this particular case, a mutation to an aminoglycoside acetyltransferase that normally breaks down the antibiotics kanamycin and neomycin (and other structurally similar antibiotics) results in an enzyme that can still breakdown aminoglycoside antibiotics, but can now break down structurally unrelated fluoroquinone antibiotics (eg. ciprofloxacin) .

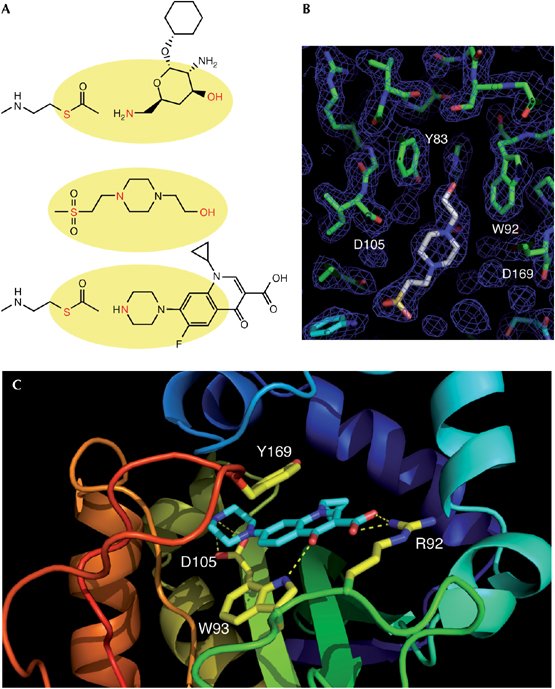

Figure 3 from Maurice F, Broutin I, Podglajen I, Benas P, Collatz E, Dardel F. Enzyme structural plasticity and the emergence of broad-spectrum antibiotic resistance. EMBO Rep. 2008 Feb 22; A shows the structure of one of the standard amionglycoside antibiotics, the counter-ion HEPES and ciprofloxacin, B shows how HEPES fits into the standard aminoglycoside acetyltransferase Ib, with important binding sites identified, C shows how the mutant binding sites now fit ciprofloxacin into the enzyme.

Figure 3 from Maurice F, Broutin I, Podglajen I, Benas P, Collatz E, Dardel F. Enzyme structural plasticity and the emergence of broad-spectrum antibiotic resistance. EMBO Rep. 2008 Feb 22; A shows the structure of one of the standard amionglycoside antibiotics, the counter-ion HEPES and ciprofloxacin, B shows how HEPES fits into the standard aminoglycoside acetyltransferase Ib, with important binding sites identified, C shows how the mutant binding sites now fit ciprofloxacin into the enzyme.

This is particularly significant, as the wholly synthetic fluoroquinones have never been present in the environment before humans produced them. The first report of metabolic resistance to fluoroquinones was in 2006, so this is a recently evolved mutation. A single mutation is enough to produce an enzyme that can break down fluoroquinones (Robicsek et al, 2006). This shows just how mutable proteins are, and how very simple changes can produce significant novel metabolic pathways. Remember, the enzyme can now act of a wholly synthetic chemical, never present in the environment before, which doesn’t look like the natural substrate for this enzyme.

In this particular case, we can easily recreate the mutations that lead to the development of fluoroquinone metabolizing enzymes. Contra Wells, we can explain the origin of this enzyme without hypotheticals. What about penicillin resistance?

Beta lactamases, a group of enzymes which break down penicillin, have diverse origins, but most trace their lineage to a group of cell wall synthesis enzymes, the D-Alanine D-Alanine peptidases (which in turn are minor modifications of more general peptidase enzymes). We can test the idea that beta-lactamases originated from D-Alanine D-Alanine peptidases by making the same putative mutations in D-Alanine D-Alanine peptidase and see if we can produce a beta lactamase. In fact, a single mutation is all it takes to convert a D-Alanine D-Alanine peptidase to a beta-lactamase (Peimbert M, Segovia L. 2003).

The D-Alanine D-Alanine peptidases have generated a number of different antibiotic resistance proteins. It only takes a single mutation in a D-Alanine D-Alanine peptidase to convert it to a vancomycin resistance enzyme (Park et al 1996). Our understanding of the evolution of antibiotic resistance, far from being predicated on “unlikely mutations over unimaginable times”, is based on very likely mutations over a few decades, that we can, and have, tested experimentally.

Now, you just have to go to the original Science Daily report to see Wells is wrong, that the researchers have both the ancestor and the evolved enzyme. No hypothetical mutations needed. If you expend a bit more effort you can go to the linked abstract from the actual paper, or do a Wikipedia search of antibiotic resistance, to see that Wells is is very wrong. Who did Wells think he was fooling?

Wells wrote:

Yet Mendel’s theory of genetics contradicted Darwin’s, and Darwinists rejected Mendelian genetics for half a century.

While Mendels’s theory of genetics didn’t quite contradict Darwins’s theory of genetics (they were both particulate theories, but Darwin’s was a somatic cell based theory), it did contradict the most widely held theories of inheritance at the time (blending inheritance - almost no-one accepted Darwin’s theory of inheritance, even people who accepted evolution and natural selection).

Importantly, Mendel’s theory did support Darwin’s theory of natural selection, by showing how variants would not be lost over time (as they were with blending inheritance). Darwinists didn’t reject Mendel’s theory. Mendel’s theory was originally ignored partly because published in an obscure journal with limited distribution and partly because it attempted a radical mathematical analysis of biology that the few people who read Mendel’s paper did not understand. It was rediscovered by evolutionary biologists in 1900 seeking to understand heredity. Biologists of all stripes rapidly took the theory up. This can all be found at Wikipedia and other online sources, so it is hard to see what Wells is hoping to accomplish with his farrago of nonsense.

Mendel’s work was heavily promoted by evolutionary biologists who thought saltation (mutational jumps) drove evolution. The big problem for natural selection was that although Mendelian inheritance explained how favourable traits could persist and not be diluted out, the traits appeared to be binary, you either had a trait or not (incomplete dominance not withstanding). How could it explain traits that appeared to have continuous variation? This was solved between 1918 by statistician RA Fischer and the 30’s by Sewall Wright, JSB Haldane and others, leading to the “Modern synthesis” of the 40’s which fused Darwin’s ideas with population genetics, leading to one of the most fruitful research programs in biology until the modern molecular biology era. In no sense could Darwinian evolutionary biologists be said to “reject” Mendelian inheritance. Indeed Fischer saw biometry as a way of reconciling the discontinuous nature of Mendelian Inheritance with the continuous variation seen in nature.

Again, the thing is any body with a computer and access to Wikipedia can find out this history. Who did Wells think he was fooling?

Wells wrote:

And although an understanding of genetics is important when dealing with antibiotic resistance, Darwin’s theory of the origin of species by natural selection is not.

This is the exact opposite of the truth. Mendelian genetics describes the particulate nature of the gene, and how these particulate genes are inherited. Natural selection describes how these particulate genes spread through the population, based on the degree of fitness they provide to the organism. The issue is a bit simpler in bacteria, where there is usually only one copy of a gene.

We know that organisms vary, and that mutations will generate new variations, new genes, not previously seen. We know that if there is selection pressure, these genes will spread. We know that if we control the selection pressure (either by using controlled, high doses of antibiotics to ensure all bacteria are wiped out, or by using multiple antibiotics in chronic infections), we can reduce the appearance and spread of resistance genes. We can even predict the emergence of new resistant strains using evolutionary analysis (Delmas et al., 2005; Orencia et al., 2001). All this from understanding evolutionary biology

Wells wrote:

Third, Dardel and his colleagues made their discovery using protein crystallography. They were not guided by Darwinian evolutionary theory; in fact, they had no need of that hypothesis.

No, they understood that the difference between the fluoroquinone metabolizing enzyme and the parent enzyme was due to mutations, so they sought out the sequence differences, and determined how they affected the structure. As well, based on the structural flexibility they determined, they made predictions of the likely ability of the parent and child enzymes to evolve further, novel actions and antibiotic substrates, based on known selection pressures.

Wells wrote:

So how, exactly, is Darwinian evolution essential to understanding and overcoming antibiotic resistance as the Darwinists claim it is?

Understanding how novel mechanisms arise via mutation, understanding how selection pressure makes these mutant genes spread, understanding how to modify selection pressure to reduce/prevent the spread of antibiotic resistance genes. Understanding the importance of the structural basis of the target mutations. That’s how.

You can intelligently design your antibiotic all you like, make it fit snugly into its target enzyme, make it resistant to degradation by the current crop of degradation enzymes. But if you don’t take account of the evolutionary potential of the bacterial enzymes and the target enzyme, and understand how resistance spreads, then your intelligently designed antibiotic is toast before it even gets through clinical trials (crunchy, tasty and easily broken down).

update:Orac has weighed in on this article as well. PZ Myers mentions it as well.

References:

- Delmas J, Robin F, Carvalho F, Mongaret C, Bonnet R. Prediction of the evolution of ceftazidime resistance in extended-spectrum β-lactamase CTX-M-9. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2006; 50: 731–738.

- Orencia MC, Yoon JS, Ness JE, Stemmer WPC, Stevens RC. Predicting the emergence of antibiotic resistance by directed evolution and structural analysis. Nat Struct Biol 2001; 8: 238–242.

- Park IS, Lin CH, Walsh CT. Gain of D-alanyl-D-lactate or D-lactyl-D-alanine synthetase activities in three active-site mutants of the Escherichia coli D-alanyl-D-alanine ligase B. Biochemistry. 1996 Aug 13;35(32):10464-71.

- Peimbert M, Segovia L. Evolutionary engineering of a beta-Lactamase activity on a D-Ala D-Ala transpeptidase fold. Protein Eng. 2003 Jan;16(1):27-35.

- Robicsek A, Strahilevitz J, Jacoby GA, Macielag M, Abbanat D, Park CH, Bush K, Hooper DC. Fluoroquinolone-modifying enzyme: a new adaptation of a common aminoglycoside acetyltransferase. Nat Med. 2006 Jan;12(1):83-8. Epub 2005 Dec 20.

- Maurice F, Broutin I, Podglajen I, Benas P, Collatz E, Dardel F. Enzyme structural plasticity and the emergence of broad-spectrum antibiotic resistance. EMBO Rep. 2008 Feb 22;