Evolution of the Heart

Hearts come in a variety of shapes and forms all the way from single chambered hearts to multi-chambered hearts with 2, 3 and even 4 separate chambers. How could evolution have achieved such a feat one may wonder, and indeed creationists have held up this minor mystery as something evolutionary theory could and would never be able to explain.

As is so often the case with such gap arguments, science has not failed to disappoint our creationist friends.

Science Daily gives us a hint of what science has uncovered in an article called Hearts Or Tails? Genetics Of Multi-chambered Heart Evolution

The expanded cardiac field in Ets1/2-activated mutants results in a proportion of animals having a functional, two-chambered heart. “The conversion of a simple heart tube into a complex heart was discovered by chance, but has general implications for the evolutionary origins of animal diversity and complexity”, says Mike Levine, a co-author of the paper.

In the last few years, the study of a very simple chordate has provided science with a unique understanding of plausible pathways for the evolution of the heart. Based on science’s previous state of ignorance, creationists have claimed rather foolishly (St Augustine) that the heart could never be explained from an evolutionary perspective.

And yet….

In “FGF signaling delineates the cardiac progenitor field in the simple Ciona intestinalis chordate” by Brad Davidson, Weiyang Shi, Jeni Beh, Lionel Christiaen and Mike Levine published in Genes & Dev. 2006 20: 2728-2738

Part of the abstract tells us the story

Conversely, application of FGF or targeted expression of constitutively active Ets1/2 (EtsVp16) cause both rostral and caudal B7.5 lineages to form heart cells. This expansion produces an unexpected phenotype: transformation of a single-compartment heart into a functional multicompartment organ. We discuss these results with regard to the development and evolution of the multichambered vertebrate heart.

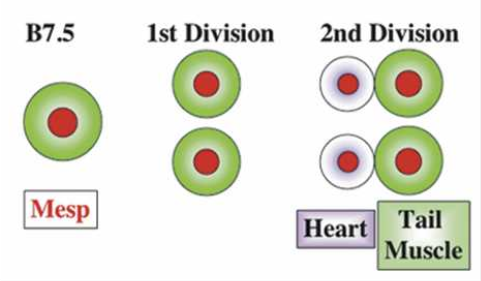

What did the researchers find? Mesp, which in most vertebrates is involved in cardiac development, is in Ciona limited to a single pair of blastomeres (B7.5). The ones in front develop into a primitive heart, the ones in the back develop into the tail. So how do the cells ‘know’? Through localized induction, via the expression of Ets1/2 which is activated in the front half of the B7.5 lineage but not in the rear ones.

So far, these findings are interesting by themselves, however the scientists also discovered that if Ets1/2 is not asymmetrically induced, but rather in both the front and rear B7.5 cells, two separate heart chambers develop.

Figure 7. Supplemental heart progenitor cells generate a second myocardial compartment. (A) Transgenic Mesp-GFP tadpole, ventral view. (B) Transgenic Mesp-GFP, Mesp–EtsVp16 tadpole, ventra–lateral view. (C) Sequential frames from a movie of a Mesp–EtsVp16 transgenic juvenile heart (Supplementary Movie S3). In the bottom row, the pericardium is outlined in red and the myoepithelium is outlined in blue. The blue line indicates a peristaltic contractile wave visualized as it meets the plane of focus. The second chamber is outlined in purple. (Second and fourth panels) Note how rhythmic expansion of the small upper chamber is synchronous with progression of the peristaltic wave within the larger lower compartment (blue arrows). See Supplementary Movies for dynamic visualization of the distinct heart phenotypes; independent contraction of the two compartments is particularly evident in Supplementary Movies S4–S6.

In other words, a functional two-chambered heart developed.

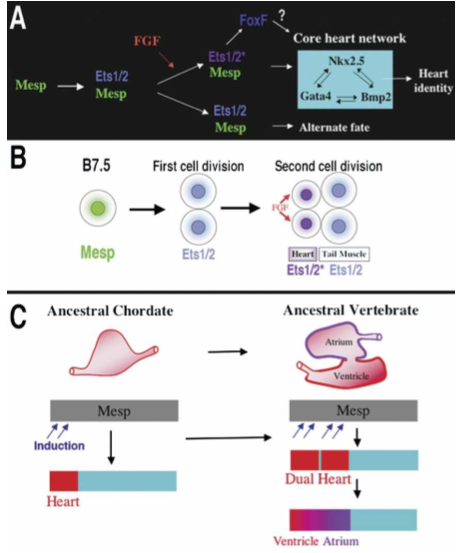

Figure 8. Models for the heart specification network and chordate heart evolution. (A) Summary of the gene network controlling heart specification in Ciona. Mesp drives expression of Ets1/2 in all descendants of the B7.5 blastomeres. FGF signaling activates Ets1/2 in the rostral daughters, leading to the expression of FoxF and ultimately to the deployment of the heart differentiation cassette. (B) Summary diagram illustrating heart specification events on the cellular level. (C) Diagram illustrating a model of chordate heart evolution. According to this model, expansion of induction within a broad heart field led to the emergence of a dual heart phenotype (as illustrated experimentally through manipulation of Ets1/2 activation in Ciona embryos). In basal vertebrates, this transitional organ was patterned and modified to form two distinct chambers.

The conclusions are that

Evolutionary origins of the multichambered vertebrate heart

Our findings support the hypothesis that a key transition in the emergence of dual-chambered hearts in the ancestral vertebrate involved recruitment of additional heart precursor cells (Fig. 8C). All extant vertebrate species have hearts with at least two chambers. In basal vertebrates (lamprey and teleosts), the heart already contains both ventricular and atrial chambers. Developmental studies indicate that the left ventricle represents the ancestral chordate heart compartment (Christoffels et al. 2004; Buckingham et al. 2005; Simoes-Costa et al. 2005). Progenitor cells of the atrium lie posterior to the ventricular field and will revert to a ventricular fate in the absence of retinoic acid signals or atrial-specific gene expression (Hochgreb et al. 2003). Modularity in the cis-regulatory elements of vertebrate Nkx2.5 genes suggests that new compartments arose in a “progressive” manner (Schwartz and Olson 1999). There are no species, in the extant or fossil fauna, representative of the transitional stage between the dual chambered heart of basal vertebrates and single-compartment hearts of invertebrate chordates, such as Ciona. Our study demonstrates that subtle changes in inductive signaling are sufficient to increase cardiac recruitment within a broad heart field(delineated by Mesp expression). Furthermore, this recruitment can potentiate the formation of new compartments through an intrinsic mechanism. This primitive multicompartment organ would then be gradually modified to exploit the selective advantage of independent inflow and outflow compartments (Moorman and Christoffels 2003; Simoes-Costa et al. 2005), leading to the formation of an ancestral dual-chambered vertebrate heart. Recent work indicates that the subsequent evolution of the right ventricle and outflow tract may also depend on the recruitment of a “secondary” progenitor population, neighboring the ancestral ventricular/atrial field (Christoffels et al. 2004).

The authors emphasize how our increased understanding of development of embryos has shown us how:

Compartmentalization of the Ciona heart in transgenic EtsVp16 juveniles provides a dramatic demonstration of how subtle changes in embryonic gene activity can potentiate the formation of novel adaptive traits. The evolutionary diversification of external appendages, including beak morphology in Darwin’s finches, have also been mimicked experimentally through perturbing gene activity within embryonic progenitor fields (Sanz-Ezquerro and Tickle 2003; Abzhanov et al. 2004; Harris et al. 2005; Kassai et al. 2005). These cases illustrate how shifts in proliferation or recruitment patterns within embryonic progenitor fields can generate novel structural complexity. Our study differs from these previous examples in that it involves an internal organ and relies primarily on shifts in patterns of recruitment rather than growth. Increased proliferation of primordia is likely to be highly constrained within the more rigid confines surrounding internal organs. Therefore, altering the distribution of progenitor cells represents a more suitable mechanism for potentiating diversification of internal morphology. We propose that variation in patterns of progenitor cell recruitment may have a general role in the evolution of novel internal structures, particularly those arising from interconnected fields, such as the pancreas, liver, and lung (Deutsch et al. 2001; Serls et al. 2005; Tremblay and Zaret 2005).

Embryology is uncovering how evolution proceeded through minor changes in regulatory expressions with significant morphological changes, showing how evolutionary processes are extremely capable in explaining the evolution of internal organs as well as the evolution of lets say the whale nostrils which moved from the snout to the top of the head.

HT: Our Christian friend and skeptic, Jacob who may be available to explain how ID creationism explains this?