I See Red (not quite protein-protein binding)

There is a wonderful article in todays issue of Nature on bioluminescent organisms in the deep seas. We like to think of the deep seas as dark, since virtually no light filters into the abyssal depths from above. However, the deep sea abounds with bioluminescence, bacteria and sea life of all sorts glow gently in the depths, enough to seriously hamper the Antares deep sea neutrino telescope that is searching for the flashes of light the represent the rare interactions of neutrinos with other matter (subscription required).

As fascinating as bioluminescence is in its own right, the article links to an amazing paper. One that puts yet another dent (if that is possible) in Dr. Behe’s key thesis; that multi-amino acid binding sites are difficult to evolve. But how does the ability of a fish to see red refute a central argument of Dr. Behe’s “Edge of Evolution”

In the abyssal depths, most fish (and other organisms) are sensitive to blue light, as red light is heavily absorbed by the depth of water overhead. In fact, most are blind to red light, a fact that marine biologists use to observe deep sea denizens unobtrusively, by illuminating the study area in red light. However, some organisms have evolved to take advantage of this red blindness. Some species of befanged dragon fish have developed red bioluminescence, which allows them to see, but remain unseen, in the dark depths.

One of these dragonfish species is even more remarkable, in that it has no red sensing pigment itself, but uses bacteriochlorophyll to harvest the red light. Chlorophyll is the pigment plants and many bacteria use to capture light for photosynthesis. How dragonfish acquire this chlorophyll is not clear at the moment.

Right now you are scratching your heads and saying, “Alright, that’s pretty amazing, but how does dragonfish seeing with chlorophyll have any bearing on Behe’s claim that protein-protein binding sites are hard to evolve?”

Proteins bind to each other by matching up knobs and depressions on the proteins surfaces, in much the same way that a key fits into a lock. It is a bit more complicated to be sure, as well as matching shapes, the amino acids that makeup the proteins surface cam be neutral, charged or oily, and these properties have to match as well. Also, both the lock and the key are “floppy” as proteins are flexible and can (and do) move and flex so that what you think are not complementary shapes can flex into shapes that bind. Nonetheless, the lock and key analogy is helpful to visualize proteins binding to each other.

Lock and Key binding using the small molecule adrenaline as an example

Lock and Key binding using the small molecule adrenaline as an example

Now, where does chlorophyll fit in? The above lock and key model is also valid for binding of small molecules. Everything I said about protein-protein binding applies exactly to protein-small molecule binding. Small molecules have to fit the shape, charge and “oilyness” of the protein “lock” too,

Dr. Behe claims that at least 3 or more amino acids must be mutated simultaneously before a partner protein can bind to another protein with high affinity (and a selectable activity). The same should hold for small molecules as well, if Dr. Behe’s assumptions are true, as most bind to proteins in special pockets to three or more specific amino acids. So, if Dr. Behe’s claims are true, then we would expect it vanishingly unlikely for any random small molecule to bind with reasonable affinity to a protein and result in a selectable activity. This is where chlorophyll comes in.

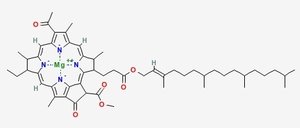

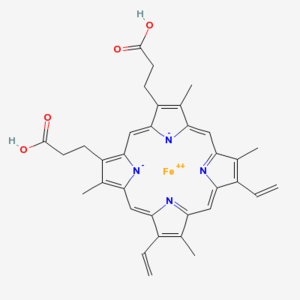

Chlorophyll (top) and Heme (bottom)

Chlorophyll (top) and Heme (bottom)

Chlorophyll is a copper magnesium containing molecule[1] that is similar to the iron containing heme molecule; the oxygen-binding component of haemoglobin. When red cells break down, there release their heme. Free heme is mildy toxic, and the body has fairly efficient ways of getting rid of it. You can also imagine that there is selection against heme binding for those proteins that don’t actually use it (such as haemoglobin and other enzymes that use iron as a catalyst), clamping a mildly toxic compound to the outside of a protein is not a good survival plan. So one would expect that the surfaces of non-heme proteins would be under selection pressure to avoid binding heme like molecules like chlorophyll. Wouldn’t you?

To determine how chlorophyll works as a visual pigment, researchers injected mice with a water soluble metabolite of chlorophyll (see the free online paper ). Remember, chlorophyll is a plant pigment that is alien to the tissues of vertebrates. This molecule was not only selectively taken up by the eye, but was concentrated almost exclusively in the retina, in the pigment layer.

And that’s not all;the injected mice were now able to respond to red light! The chlorophyll metabolite was acting as a visual pigment, harvesting light and passing the energy on to the visual pigments of native mouse photoreceptor cells.

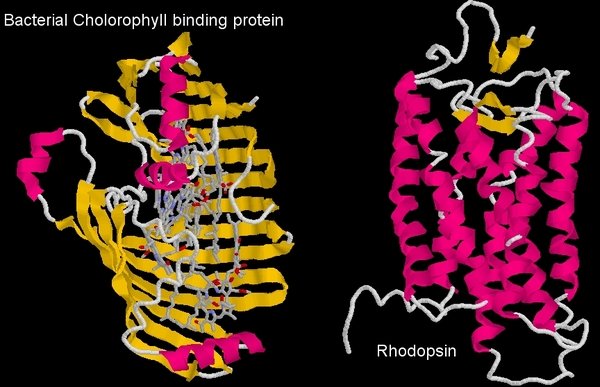

Comparison of the structure of the bacterial chlorophyll binding protein and Rhodopsin, the mammalian visual pigment

Comparison of the structure of the bacterial chlorophyll binding protein and Rhodopsin, the mammalian visual pigment

In order to transfer energy to the visual pigment protein, the chlorophyll must bind to it. Now, the diagram above shows the bacterial protein that normally binds chlorophyll, and the visual pigment protein. You can see immediately that they are very different proteins (one is like a clamshell, the other a tube, and the visual pigment, rhodopsin, is not a heme binding protein). The coordinating amino acids that bind chlorophyll in the bacterial protein (or the plant protein for that matter) are absent in the visual pigment protein, so it’s not a case of chlorophyll binding to a similar molecule and doing what it did before.

So, in the absence of any mutations, a small molecule that needs to bind to multiple amino acids of a protein in a distinct orientation to work, can bind to a completely different protein, unrelated to its normal binding partner in a species that never normally sees this small molecule in its tissues and provide a selectable function, right off the bat.

That is astounding. According to Dr. Behe’s arguments (which apply equally well to small molecule-protein interactions as to protein-protein interactions), this sort of interaction is vanishingly unlikely. Yet we see it. This shows once again that Dr. Behe’s arguments about binding and selectability are fatally flawed.

It’s enough to make an ID supporter see red.

[1] Yeah, major dimness attack, I could even see the magnesium ion in my own diagram!