Of cilia and silliness (more on Behe)

Well, my own personal copy of Michael Behe’s new book The Edge of Evolution arrived via amazon.com today, so I suppose it is fair game. I have linked to a few early blog comments (see more from ERV), and Michael Ruse has a short newspaper comment out today. And several other reviews are coming out in the near future in Science, Discover, etc. None of them positive at all, but it’s amazing how much attention someone can get by sacrificing scientific rigour and inserting divine intervention instead.

Well, my own personal copy of Michael Behe’s new book The Edge of Evolution arrived via amazon.com today, so I suppose it is fair game. I have linked to a few early blog comments (see more from ERV), and Michael Ruse has a short newspaper comment out today. And several other reviews are coming out in the near future in Science, Discover, etc. None of them positive at all, but it’s amazing how much attention someone can get by sacrificing scientific rigour and inserting divine intervention instead.

I don’t have a full review of the book and I won’t for a bit since I am working on other things. But I want to get dibs on one peripheral but particularly shocking and egregious error that Behe makes in The Edge of Evolution. The error is simple but it points to what I have become convinced is the true core of the mishmash known as “intelligent design”: sloppiness and wishful thinking.

Most of The Edge of Evolution is engaged in trying to prove that protein-protein binding sites can’t evolve without intelligent guidance, using humans vs. malaria and humans vs. HIV as his primary examples. (Yes, at the end, on p. 237, Behe writes, “Here’s something to ponder long and hard: Malaria was intentionally designed. The molecular machinery with which the parasite invades red blood cells is an exquisitely purposeful arrangement of parts.” Well, at least he’s consistent. More on this in future posts I imagine.). Behe mostly doesn’t even address the criticisms of his previous arguments, doesn’t update his case, acknowledge previous errors, etc. He doesn’t explain why anyone should take him seriously when he claimed in Darwin’s Black Box that scientists had “no answers” on the evolutionary origin of the immune system and was then shown up in court and in print via a massive amount of research published in top journals that showed he was wrong (see PT and NCSE and especially Nature Immunology).

However, Behe does devote one chapter, chapter 5, to an update of one of his examples from Darwin’s Black Box. Chapter 5, “What Darwinism Can’t Do,” (pp. 84-102) is devoted to the eukaryotic flagellum/cilium. (Because this apparently still confuses many, please note that the eukaryotic cilium or flagellum is entirely different from the bacterial flagellum, which is entirely different from the archaeal flagellum. They are no more similar than insect wings and bird wings. See here for a summary of the differences.)

In chapter 5, Behe reviews the cilium as known from a standard lab organism, the single-celled green alga Chlamydomonas, aka Chlammy to her friends. Starting on page 87, Behe introduces a new twist to the cilium argument, which is that since the mid-1990s scientists have discovered some fascinating new details about how cilia are assembled in the cell. Essentially, a multiprotein system known as intraflagellar transport, or IFT, attaches to the cilium axonome (the 9+2 structure made of microtubules, which are made of tubulin), grabs the necessary protein subunits (like tubulin) from inside the cell, and “walks” them along the axoneme of the cilium out to the tip, where the subunits are deposited. The IFT complex then “walks” back to the bottom of the cilium to pick up more subunits.

It is more complex than this, of course…it is much easier to just look at a diagram to get a sense of what is going on. For example, from an online textbook on the lab nematode C. elegans:

You can see that kinesin motor proteins walk the cargo out to the tip, and dynein motor proteins, which were handily brought along for the ride, walk the leftovers back. You can even see some spiffy videos on Joel Rosenbaum’s website at Yale.

Now, this is pretty cool stuff, and Behe plays it for all it’s worth. First, Behe points out all kinds of genetic diseases that occur in humans that are due to cilia malfunction, some of which are due to defects in IFT proteins. Clearly, not only is the cilium irreducibly complex, so is the IFT complex that assembles it! Behe entitles this section “IRREDUCIBLE COMPLEXITY SQUARED!” Watch out, evolution!

Behe goes for the jugular on p. 94:

IFT exponetially increases the difficulty of explaining the irreducibly complex cilium. It is clear from careful experimental work with all ciliated cells that have been examined, from alga to mice, that a functioning cilium requires a working IFT.12 The problem of the origin of the cilium is now intimately connected to the problem of the origin of IFT. Before its discovery we could be forgiven for overlooking the problem of how a cilium was built. Biologists could vaguely wave off the problem, knowing that some proteins fold by themselves and associate in the cell without help. Just as a century ago Haeckel thought it would be easy for life to originate, a few decades ago one could have been excused for thinking it was probably easy to put a cilium together; the piece could probably just glom together on their own. But now that the elegant complexity of IFT has been uncovered, we can ignore the question no longer.

[…endnote 12 is on p. 285, and is quoted at the bottom of this post in footnote 1 for completeness]

In the next paragraph Behe briefly dismisses a recent paper on the evolutionary origin of cilium in endnote 13 (Jekely and Arendt (2006), “Evolution of intraflagellar transport from coated vesicles and autogenous origin of the eukaryotic cilium.” Bioessays 28:191-198) and pretends that other work doesn’t exist. [See note 2] And never mind the minor point that dynein (for example) has cytoplasmic versions with diverse transport functions in the cell apart from intraflagellar transport, including involvement in mitosis, and the fact that dynein itself is the primary motor protein of cilial motility, and that dynein has widespread homologs in eukaryotes and prokaryotes. I mean, really, who could possibly care about discussing data that would be fundamental to any thorough discussion of the origins of the cilium?

But the problems I mention above are details. Expecting Behe to deal seriously with homology data is like expecting young-earth creationists to deal with 11,000 continuous years of tree rings: totally ridiculous. But I haven’t even gotten to the big problems yet.

The huge problem with Behe’s invocation of intraflagellar transport in his “IRREDUCIBLE COMPLEXITY SQUARED” section of chapter 5 is that he is completely wrong when he says that intraflagellar transport is universally required for cilium construction! Anyone can see this by reading this 2004 paper by Briggs et al. in Current Biology, which they cleverly entitled “More than one way to build a flagellum,” presumably so that people would find out that there is…wait for it…more than one way to build a flagellum.

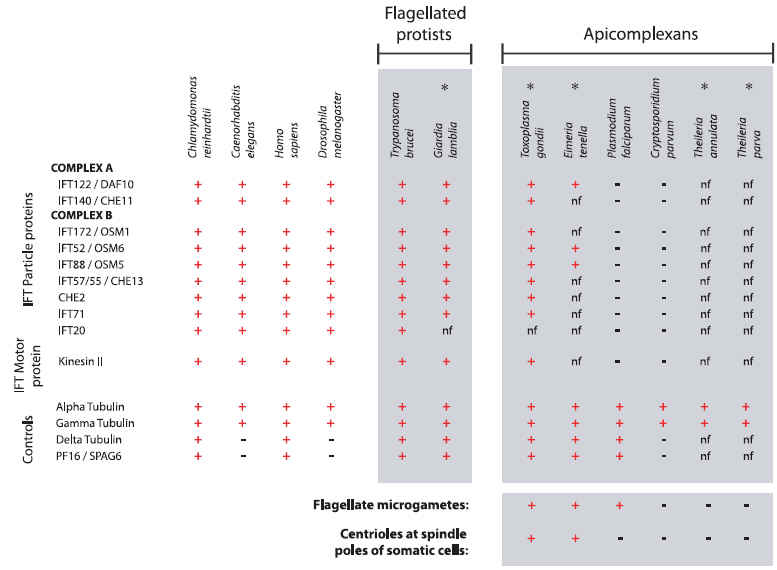

It turns out that when you look at a number of recently-sequenced genomes, a pattern emerges: organisms with cilia have IFT genes, and organisms without cilia don’t. So far this is Behe’s expected pattern. However, as with most things in biology, there is an exception to the rule. Check out Figure 1 of Briggs et al.:

You will note that the third column in the Apicomplexans section shows that one of the parasitic apicomplexans completely lacks the IFT genes…yet makes a cilium anyway! This reminds me of something another critic of Behe once said, in a different context:

Contrary to claims about irreducible complexity, the entire ensemble of proteins is not needed. Music and harmony can arise from a smaller orchestra.

(Note: fans of Behe’s reply to Doolittle should read the PT post “Clotted rot for rotten clots”)

Apparently what is going on is that this particular apicomplexan assembles its cilia in the cytoplasm, and therefore has ditched the elaborate IFT complex that would otherwise be needed to transport building materials out to the far-removed end of the cilium. Not only does this one parasitic protozoan get away with this trick, apparently it also happens with Drosophila sperm. Behe would have known all this if he had only carefully read the Jekely and Arendt (2006) cilium evolution paper that he dismissed with a hand wave. As they write on page 193,

The [IFT] complex is only lacking from species that have secondarily lost their cilia, as Dictyostelium, yeasts and flowering plants, or from species with cilia that do not rely on IFT (in the parasite Plasmodium cilia assemble in the cytoplasm(48)). Cytoplasmic assembly of cilia is a derived feature that has independently evolved in Drosophila sperm.(49)

Now, Jekely and Arendt (2006) note just before this that “IFT is ancestrally and almost universally associated with cilia,” so apparently the last common ancestor of modern cilia had an IFT complex (and Jekely and Arendt base their paper on comparing IFT to homologous intracellular transport systems in eukaryotic cells). But it really doesn’t help the “irreducible complexity” argument much if Behe’s favorite system, the eukaryotic cilium, and the extra-favorite “irreducible complexity squared” system, intraflagellar transport, on which he bases a whole chapter, is in fact entirely reducible.

Surely, someone – Behe himself, or one of the “peer-reviewers” that the IDers will probably allege the book had, should have caught this. But if they had, Behe would have had to completely scrap chapter 5. In real peer-review, that’s the shakes, but in creationism/ID-land this sort of thing is unfortunately par for the course. In creationism/ID, one guy’s personal knowledge about a topic, usually a personal knowledge based at most on textbooks and not a thorough survey of the literature, is regularly taken to be the sum total of biological knowledge, and via this processes a whole bogus folk-creationist biology is built up about field after field. For example with fossils, thousands of creationists/IDers think there are no transitional fossils based on a few bogus misquotes of Stephen Jay Gould about punctuated equilibria, which they almost universally mistakenly think was about something other than small transitions between closely-related species; or bacterial flagella (see here – no IDer has yet acknowledged this mistake, which they are still perpetuating in print). This gets me back to my original point: a great deal of creationism/ID boils down to sloppy claims made on insufficient information, plus wishful thinking that blocks the impulse to double-check one’s claims against previous research. Once you become alerted to this feature of ID you will see it everywhere.

Oh, I almost forgot the best part: Which apicomplexan critter is it that builds cilia despite Behe’s declaration that “a functioning cilium requires a working IFT”? Why, it’s Plasmodium falciparum, aka malaria, aka Behe’s own biggest running example used throughout The Edge of Evolution. Yes, it’s the very critter about which Behe wrote on page 237,

“Here’s something to ponder long and hard: Malaria was intentionally designed. The molecular machinery with which the parasite invades red blood cells is an exquisitely purposeful arrangement of parts.”

But not, apparently, the parts which Behe thought were required for cilium construction. If there is an Intelligent Designer up there, I suspect He’s having a bit of a chuckle right now.

Footnotes

Note 1. Behe’s endnote 12 for chapter 5:

- Berriman and coworkers write of trypanosomes: “The proteins of the flagellar axoneme appeared to be extremely well conserved. With the exception of tektin, there are homologs in the three genomes for all previously identified structure components as well as a full complement of flagellar motoros and both complex A and complex B of the intraflagellar transport system…. Thus, the 9+2 axoneme, which arose very early in eukaryotic evolution, appears to be constructed around a core set of proteins that are conserved in organisms possessing flagella and cilia” (Berriman, M., et al. 2005. The genome of the African trypanosome Trypanosoma brucei. Science 309: 416-22).

Note 2. Work like:

* David R. Mitchell (2004). “Speculations on the evolution of 9+2 organelles and the role of central pair microtubules.” Biology of the Cell. 96, 691–696.

* David R. Mitchell (2006). “The Evolution of Eukaryotic Cilia and Flagella as Motile and Sensory Organelles.” In: Origins and Evolution of Eukaryotic Endomembranes and Cytoskeleton, edited by Gáspár Jékely.

* Thomas Cavalier-Smith (1987). “The Origin of Eukaryote and Archaebacterial Cells.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 503, 17-54.

For Cavalier-Smith (1987), I particularly like Figure 5 and the caption on pp. 38-39. Although it needs an update since it is 20 years old, it still provides a good big-picture view of how cilium evolution is just a piece of the evolutionary origin of mitosis. Download jpgs of part 1, part 2, part 3.

You’ve never heard of this paper from the ID guys? Not surprising, they’ve never cited it. Cavalier-Smith pointed this out way back in his 1997 review of Darwin’s Black Box in TREE (see Cavalier-Smith, 1997, “The Blind Biochemist,” Trends in Ecology and Evolution 12(4), 162-163, April 1997), and I’ve never seen any IDer acknowledge the oversight. Stumbling on this review while looking up this other book review is literally what got me into this whole ID thing in the first place. I had originally thought, “Hmm, Behe might have a point about the lack of literature on the evolution of complex systems.” Then I read Cavalier-Smith’s review and realized I’d been snookered. The rest is history.

Note 3. This doesn’t go with anything, but for the record, Mike Gene, perhaps the ID guru who is most respected for usually having a clue about the biology he is talking about unlike virtually all of the rest of them, made the same mistake Behe made about IFT. See Mike Gene’s “ASSEMBLING THE EUKARYOTIC FLAGELLUM: Another example of IC?” and “THE NEGLECTED FLAGELLUM.”

Note 4. This is also not referenced in the main text, but the wikipedia intraflagellar tranport page also contains the “always required” mistake.