Axe (2004) and the evolution of enzyme function

Douglas Axe recently (well, sort of) published an article in the Journal of Molecular Biology entitled “Estimating the Prevalence of Protein Sequences Adopting Functional Enzyme Folds” (Axe, J Mol Biol 341, 1295-1315, 2004). In his discussion of the experimental observations, Dr. Axe mentions some numbers that are likely to generate much discussion amongst Intelligent Design advocates and critics. For example, Stephen Meyer (2004) cites Axe at a key point in the argument in his recent article advocating Intelligent Design, “The Origin of Biological Information and the Higher Taxonomic Categories,” much discussed in previous Panda’s Thumb threads (here).

“Axe (2004) has performed site directed mutagenesis experiments on a 150-residue protein-folding domain within a B-lactamase enzyme. His experimental method improves upon earlier mutagenesis techniques and corrects for several sources of possible estimation error inherent in them. On the basis of these experiments, Axe has estimated the ratio of (a) proteins of typical size (150 residues) that perform a specified function via any folded structure to (b) the whole set of possible amino acids sequences of that size. Based on his experiments, Axe has estimated his ratio to be 1 to 10^77. Thus, the probability of finding a functional protein among the possible amino acid sequences corresponding to a 150-residue protein is similarly 1 in 10^77.”

More recently, Dembski cited Axe in his Expert Witness Report for the Dover trial (see this).

“Recent research by Douglas Axe (see Appendix 3) provides such evidence in the form of a rigorous experimental assessment of the rarity of function-bearing protein sequences. By addressing this problem at the level of single protein molecules, this work provides an empirical basis for deeming functional proteins and systems of functional proteins to be unequivocally beyond Darwinian explanation.”

Given that this subject is often raised by ID proponents (such as this), and that the Biologic Institute (where Axe works) has made some news accounts, it seems appropriate to review Axe’s work. The purpose of this PT blog entry is to try and lay out the study cited above (Axe DD, J Mol Biol 341, 1295-1315, 2004) in a form that is accessible to most interested parties, and to discuss a larger context into which this work might be placed. Needless to say, the grand pronouncements being made by the ID camp are not warranted.

Section 1. What Axe did

First, a brief overview of the experiment and results. The object of interest was the so-called large domain of the TEM-1 penicillinase, an enzyme that breaks down antibiotics related to penicillin. (Antibiotics such as penicillin are called, collectively, beta-lactams, and enzymes that break down these antibiotics and confer drug resistance are called beta-lactamases, which is why the term beta-lactamase may pop up in this blog entry from time to time.) Axe was interested in using a mutational approach to explore the constraints for forming a functional large TEM-1 domain, and applying these results to estimate of the density of functional sequences in the space of all possible amino acid sequences

The approach taken was to generate collections of randomized mutant sequence variants in a functional TEM-1 variant and “count” the numbers of mutants that retained some measure of activity. Activity was measured by growth of bacteria containing the variants on relatively low levels of ampicillin, a target (or substrate) of TEM-1. (Cells with active TEM-1 can break down the ampicillin and thus survive, whereas cells with mutant TEM-1 variants that can no longer maintain a stably-folded enzyme cannot break down the antibiotic, and this will not grow.)

Axe anticipated that the native TEM-1 would be rather “resistant” to random mutagenesis, owing to a “buffering effect” contributed by what is probably a robust structural fold. This would preclude a proper assessment of the constraints governing low-level function, which in turn are the constraints relevant to the question of the emergence of functional sequences. Accordingly, he first isolated, by targeted mutagenesis, a so-called “reference sequence”, a TEM-1 variant that was expected to be much more susceptible to the effects of mutational change. (This is a crucial aspect of the experiment, the ramifications of which are discussed in Section 2.) The variant was identified as a temperature-sensitive enzyme that permitted growth of bacteria on selective (ampicillin-containing) media at a permissive temperature (25 °C), and differs from the wild-type at 22% of the 153 positions. (“Temperature-sensitive” enzymes lose function after a small change in temperature. Here, the enzyme had some modicum of activity at a lower temperature – 25 °C – but was inactive at elevated temperatures – e.g., 37°C, the temperature at which E. coli is usually grown.)

Having generated a mutation-sensitive TEM-1 variant, Axe then set about to do the mutagenesis. For this, four ten amino-acid clusters (each of which is spatially separate from the others in the 3-dimensional structure) were partially randomized. The variations that were introduced in each cluster were designed so as to retain the general hydropathic profile (see [1]) at the positions being varied. Populations of randomized pools were plated on selective media (at the permissive temperature) and the numbers of colonies counted. From this (and from other measurements that established the total numbers of screened mutants), the relative frequency of functional mutants was determined. For two of the four clusters, a recovery rate of about 0.03% (e.g., 3x10^-4) was found. For one of the clusters, a rate of 1 in 10^5 was seen. No functional variants for one of the clusters were isolated; based on the total numbers of clones analyzed, this sets a limit of 2x10^-5 as the frequency of functional mutant for the large domain of TEM-1.

These are the experiments and “raw data”. Axe averaged these four values and derived a mean per-residue tolerance to change; this value is 0.38 (roughly speaking, this is the fraction of variants at a given position that will yield a functional enzyme, and thus a functional fold). From this, he calculated that the fraction of all possible variants in the 153 amino-acid TEM-1 fold that will be functional is about 1 in 10^64 (e.g., 0.38 raised to the 153rd power).

This number represents the number of functional variants that are related to the specific reference sequence that was randomized. Axe also compared a great many naturally-occurring “relatives” of the TEM-1 fold and derived a general hydropathic “signature”. From this work, Axe estimated that about 1 in 10^33 of all sequences will possess the TEM-1 hydropathy signature, and hence a fold related structurally to the TEM-1 domain. Since each of the properly-folded (1 in 10^33) variants might be expected to possess a similar range of individual functionality (e.g., 1 in 10^64 or the family of sequences related to each variant is expected to be functional), we can estimate that 1 in 10^97 of all possible 153-mers will possess a functional TEM-1 fold.

Section 2. Going from Axe’s work to “functional proteins are isolated in sequence space” A claim that is being made by ID proponents (as in Meyer’s paper) is that work such as this shows that functional proteins are so rare in sequence space that the natural origin of new proteins is so improbable as to be effectively impossible. Briefly, the argument is (or will be) that, if function occurs only once every 10^77 sequences (to use one of the numbers from Axe’s work), then it is rather unlikely that new functions can arise in the biosphere. However, Axe’s approach does not permit such a conclusion. The following hopefully conveys this.

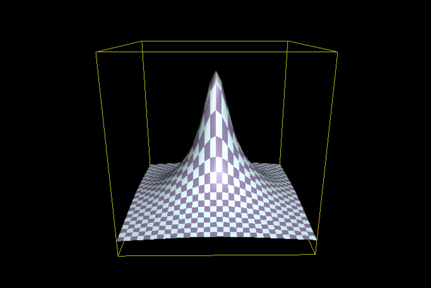

Put pictorially, the issue that ID proponents are arguing about is the relative structure, or shape, of the topography of functional sequences in all of sequence space. To illustrate, the issue becomes one of the parameters of the hill shown in this figure (we’ll call it Figure 1):

In this illustration, the base formed by the X and Y axes represents the sequence “space”, each hypothetical point or patch would depict a different sequence, and the Z-axis depicts some measure of activity. The “accessibility” of function, using this illustration, is a matter of the area of the base of the hill shown – the broader the base, the greater the number of related and functional sequences, and the greater the number of ways that function may be “found”. The idea that ID proponents push is that, if such a hill has a narrow enough base, then it is not likely that random processes can “find” even the base of the hill, let alone the peak. The experimental approach used by Axe is predicated on the assumption that the shape of this hill can be determined by assessing its susceptibility to mutation. Thus, the greater the sensitivity, the narrower the base, and the less likely is it that function can arise. ID proponents argue that Axe’s work shows that, indeed, the base is very narrow. This follows a. from the numbers given in the preceding; and b. from the nature of Axe’s experimental design.

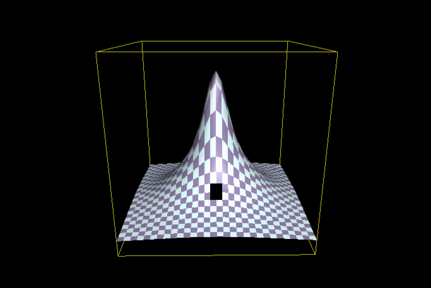

There is, however, a fly in the ointment. (Actually, there are many.) Recall that Axe did not work with the native TEM-1 penicillinase, but rather with a variant that had a lower activity. The assay system made this necessary. (Scoring bacteria on antibiotic-containing media isn’t particularly discriminating, and it’s hard to tell is, say, if a wild-type detoxifying enzyme has lost 90% of its activity.) In other words, Axe decided to select a particular part of the “hill” such as that shaded in black in the following illustration (Figure 2):

(Look carefully - the black patch isn’t very big, because Axe has limited his scope in an analogous fashion.)

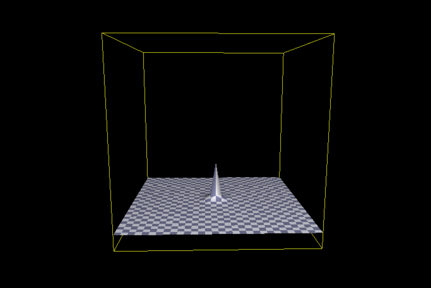

In addition, Axe deliberately identified and chose for study a temperature sensitive variant. In altering the enzyme in this way, he molded a variant that would be exquisitely sensitive to mutation. In terms of our illustrations, Axe’s TEM-1 variant is a tiny “hill” with very steep sides, as shown in the following (Figure 3):

Obviously, from these considerations, we can see that assertions that the tiny base of the “hill” in Figure 3 in any way reflects that of a normal enzyme are not appropriate. On this basis alone, we may conclude that the claims of ID proponents vis-Ã -vis Axe 2004 are exaggerated and wrong. Axe’s numbers tell us about the apparent isolation of the low-activity variant, but reveal little (nor can it be expected to) about the “isolation” or evolution of TEM-1 penicillinase. (Or any other enzyme, for that matter.)

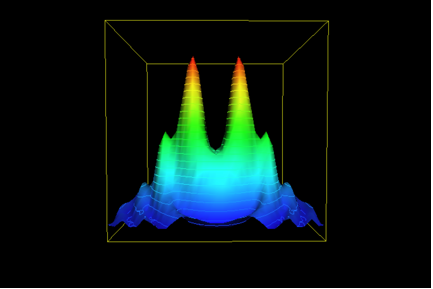

Of course, there is more. Most naturally-occurring enzymes are not isolated activities as Figure 1 would imply. Something like the next illustration (Figure 4) is a better depiction – distinct activities and enzymes are often derived from common structural and sequence themes. This expands the base of the “hill” to include those of the neighboring activities; this may be considerable indeed. (In the example of TEM-1 penicillinases, the neighbors would include DD-peptidases; Knox et al, 1996; Adediran et al., 2005.)

But there is even more. Since the “goal” of the evolutionary exercise is a catalytic activity, and not a particular structure, the possible existence of totally unrelated structures and sequences that possess a similar activity complicates matter even more. This is pertinent for penicillinases, that are beta-lactamases. We know of a number of other families of structures that include beta-lactamases (Helfand and Bonomo, 2003). One of these, the metallo-beta-lactamases (Daiyasu et al., 2001), is quite unrelated to the TEM-1 enzymes. Axe’s study does not “count” these families of enzymes (or their neighbors), nor does it acknowledge that many more such structures are at least hypothetically possible.

Section 3. So how broad is the base of the hill? That is the real question that Axe, ID proponents, and other who follow this sort of discussion would ask. To get some idea, we can turn to Axe’s paper. Axe mentions two other studies – one deals with experiments done with the lambda repressor, and the other with chorismate mutase. Work with the lambda repressor (Reidhaar-Olson and Sauer, 1990) yielded a “value” for the frequency of functional variants of 1 in 10^63 (roughly) for the 92-mer. Work with chorismate mutase (Taylor et al., PNAS 98, 10596-10601, 2001) gave a value of 1 in 10^24 for the 93 amino acid enzyme. Scaled for a similar size protein, Axe’s work gives a value of 1 in 10^59, which falls within the range established by previous work. (The literature in this area is rather large, far beyond the scope of this article to review. Suffice to say that the range of “probability” stated here is representative of the numerous studies in this area.)

Studies such as these involve what Axe calls a “reverse” approach – one starts with known, functional sequences, introduces semi-random mutants, and estimates the size of the functional sequence space from the numbers of “surviving” mutants. Studies involving the “forward” approach can and have been done as well. Briefly, this approach involves the synthesis of collections of random sequences and isolation of functional polymers (e.g., polypeptides or RNAs) from these collections. Historically, these studies have involved rather small oligomers (7-12 or so), owing to technical reasons (this is the size range that can be safely accommodated by the “tools” used). However, a relatively recent development, the so-called “mRNA display” technique, allows one to screen random sequences that are much larger (approaching 100 amino acids in length). What is interesting is that the forward approach typically yields a “success rate” in the 10^-10 to 10^-15 range – one usually need screen between 10^10 -> 10^15 random sequences to identify a functional polymer. This is true even for mRNA display. These numbers are a direct measurement of the proportion of functional sequences in a population of random polymers, and are estimates of the same parameter – density of sequences of minimal function in sequence space – that Axe is after.

10^-10 -> 10^-63 (or thereabout): this is the range of estimates of the density of functional sequences in sequence space that can be found in the scientific literature. The caveats given in Section 2 notwithstanding, Axe’s work does not extend or narrow the range. To give the reader a sense of the higher end (10^-10) of this range, it helps to keep in mind that 1000 liters of a typical pond will likely contain some 10^12 bacterial cells of various sorts. If each cell gives rise to just one new protein-coding region or variant (by any of a number of processes) in the course of several thousands of generations, then the probability of occurrence of a function that occurs once in every 10^10 random sequences is going to be pretty nearly 1. In other words, 1 in 10^-10 is a pretty large number when it comes to “probabilities” in the biosphere.

The uncertainties in estimating the densities of functional sequences are very high. Obviously, we all would like to home in on a narrower range. This is complicated by the technical and theoretical shortcomings of the various approaches. The “reverse” approach is tied to a single family of sequences and functions and makes assumptions that may not be warranted (Section 2 here is an example). The “forward” approach may find too many things, some (many?) of which may have no biological relevance. Sorting these things out is a tough nut to crack experimentally.

Summary

To summarize, the claims that have been and will be made by ID proponents regarding protein evolution are not supported by Axe’s work. As I show, it is not appropriate to use the numbers Axe obtains to make inferences about the evolution of proteins and enzymes. Thus, this study does not support the conclusion that functional sequences are extremely isolated in sequence space, or that the evolution of new protein function is an impossibility that is beyond the capacity of random mutation and natural selection.

Endnote

- the hydropathic signature is technical-ese for a particular pattern of polar and apolar amino acid residues in a structure or sequence. In the case of this study, the signature was the guide in determining the extent of variation that was introduced in the ten amino-acid clusters. Also, an aside to help readers with terminology – when we speak of sequence space, we are talking about nothing more than some collection of possible sequences. Thus, for example, the total “sequence space” of polypeptides of 153 amino acids in length is the number of possible polypeptides - 20^153, or 10^199.

Acknowledgements:

Thanks to the efforts of the PT crew, and particularly Ian Musgrave, who helped me keep this on topic. Also, many thanks are due to Douglas Axe, who graciously helped me with early drafts of this essay. Please note that all of these ideas are mine, and I make no claim that any of these thoughts represent Axe’s views.

References:

Axe DD, J Mol Biol 341, 1295-1315, 2004

Meyer SC, Proc Biol Soc Washington 117, 219-239, 2004

Knox JR, Moews PC, Frere JM. Chem Biol. 3, 937-47, 1996

Adediran SA, Zhang Z, Nukaga M, Palzkill T, Pratt RF, Biochemistry 44, 7543-52, 2005

Helfand MS, Bonomo RA., Curr Drug Targets Infect Disord 3, 9-23, 2003. (A review of different types of known beta-lactamases.)

Daiyasu H et al., FEBS Lett 503, 1-6, 2001. (A short review that describes the “connectedness” of metallo-beta-lactamases with other activities.)

Reidhaar-Olson and Sauer, Proteins: Struct Funct Genet 7, 306-316, 1990

Taylor et al., Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98, 10596-10601, 2001

Cho et al., J Mol Biol 297, 309-319, 2000 (this describes one of the first successes in using mRNA display; Pubmed searches for “mRNA display” will yield many other papers)