Steve Steve and end of the Cambrian Explosion as we know it (part 1)

As an international, jet setting public intellectual there are many calls on my time, and I find myself rushing from pillar to post with my busy diary. However, at last I was able to take up the offer of that nice Dr. Musgrave to visit Adelaide, and amongst other things, take in Chris (“how can Nedin be trusted”) Nedin’s Big Dick (Chris was so excited about it, how could I resist). Despite being nearly devoid of bamboo, Adelaide is renown in song (“just another boring night in Adelaide” “people ask me, why Adelaide?”) and justifiably famous for being perched on the edge of umpteen square kilometers of burning desert.

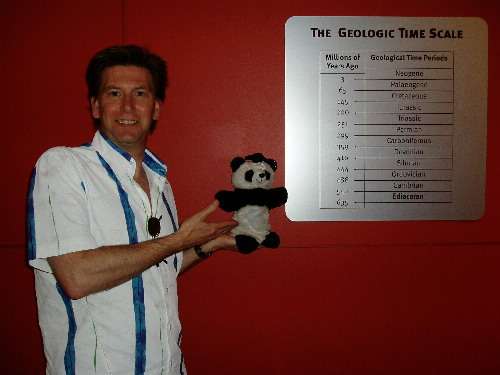

But the desert holds many treasures, one of which is the finest collection of fossils from the Ediacaran period, a Precambrian era that features lots of weird, squashy creatures and mysterious animal tracks, and some things that Intelligent Design creationists don’t want to talk about, because they throw doubt on the so-called “Cambrian Explosion” that they claim evolution can’t explain. But now a creature has been found that wipes out the Cambrian Explosion (clue, see picture).

The ID creationists like to claim that all major body plans originate in the so-called “Cambrian explosion”, a period of around 30-60 million years where there is a rapid appearance of animals with hard parts. However, ID creationists ignore the fact that things like sponges, corals, echinoderms like Arkarua, and mollusks like Kimberella make their appearance long before the Cambrian Explosion, in the Ediacaran. Note that the hyperlinks are a bit cautious about these fossils, but there has been a lot more work (and better fossils) since then (the links still call them Vendian, for goodness sakes). See this excellent review on Edicarian fossils and Kimberella and its feeding tracks. There is also another, very important group that appears in the Ediacaran, which I’ll tell you about later on (you’ll just have to wait in suspenders, I promised Nedin I would show the Big Dick first). However, all these organisms are very small and squashy (just like evolutionary biologists predicted) and don’t attract the attention that the Cambrian fossils do.

The Flinders Ranges north of Adelaide has one of the finest exposures of Ediacaran sediments, with massive fossil assemblages preserving ecological relationships, and reveals a unique window on this vanished world, so I was more that a little pleased when Musgrave (on the left of yours truly below) and Nedin (on the right below) agreed to take me to the newly opened Hall of the Ediacarans at the South Australian Museum. Now, Dr. Musgrave is a nice guy, but a bit gormless. Not only did he fail to arrange a meeting with the Museum director Tim Flannery (world renowned marsupial expert and author of “The Future Eaters”) but he forgot to bring the camera tripod, which is essential for photographing flat, nearly invisible trace fossils in low light conditions. When other people have taken me to see fossils at least they looked like fossils rather than deflated toy balloons.

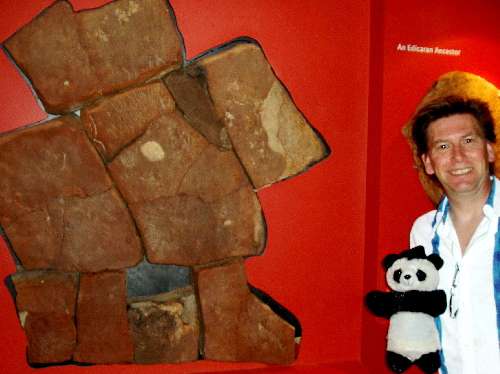

The entrance to the exhibit is fairly spectacular, they have dug up an entire slab of fossil seabed and set it upright. On the side facing the entrance is the ripple marks on the seabed, but on the side facing away is an amazing seafloor community, buried in time. There is a whole range of organisms on the face of the slab, worm-like things and mysterious helmet-like things, but the clearest organism on the slab is the minute worm-like Dikensonia that appear everywhere.

Dickensonia are everywhere, there are small ones, medium ones (like the one below) and big ones. There are traces of them crawling over algal mats feeding, we have fossils that suggest different growth stages and there are hints about their social behavior as well.

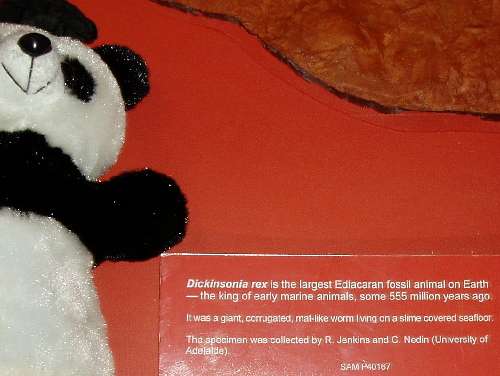

Finally though, I got to see Nedin’s Big Dick. Dickensonia rex, a monster flat worm one meter long, the pride of the Ediacaran seas.

Typically, this is where Musgrave needed a tripod to bring out the details of Dikensonia (the awful way the fossils were lit didn’t help). All you can see here is a large slab of rock with some faint striations on it, but be assured that most of that slab is covered with a giant flat worm.

And here is the nice label that shows that Nedin collected this behemoth of worminess. Even though Nedin can’t spell paleontologist, he can at least find really interesting things.

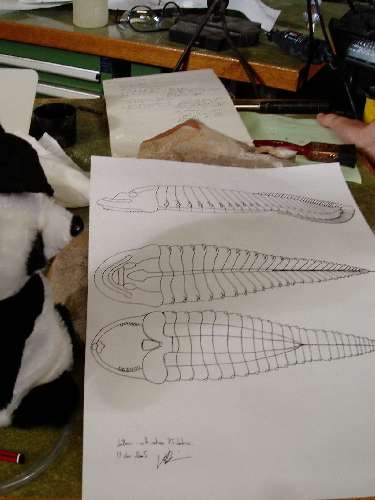

Since the gormster couldn’t photograph the Big Dick, here’s a picture of me swimming with a nice model Dickensonia.

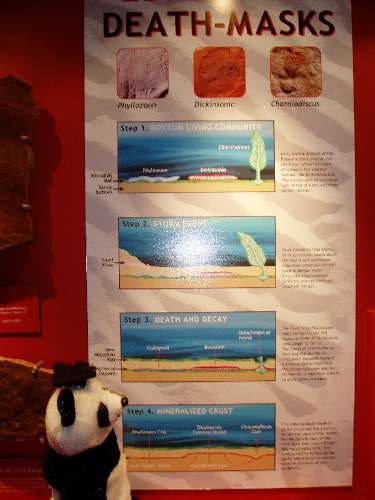

The paleontologists are able to reconstruct things like Dickensonia in such good 3D detail because many of the Flinders Ranges Ediacarans were presevered by rapid slumps of fine-grained sediment. Because entire assemblages were buried there are also lots of representative organisms in many different orientations so that a 3D image can be built up from examining multiple specimens.

Here is a magnificent Sea Pen (Charniodiscus) preserved in very good detail. This fossil was stolen from the Flinders Ranges but finally recovered and returned to Australia after nine years of heroic sleuthing.

Because of the fine level of detail in many Ediacaran deposits all sorts of small squashy beasties turn up. Including this one, the one that destroys the “Cambrian Explosion” beloved of ID creationists.

Yes, the strange looking groove you are looking at is related to all of us. You are looking at the first recorded Chordate. Now it’s a bit hard to see here, but you can see grooves that record the record the muscle bands (there’s also traces of fins, but they can’t be seen in this picture. Nedin was a bit unconvinced, and thought that it might be part of a frond animal (and as Nedin is quite intimately knowledgeable about the Ediacaran fossils, you ignore him at your peril), but there are now 18 of these fossils described, preserved in every possible orientation, so they know it is not a frond animal, but a fossil of the first chordate.

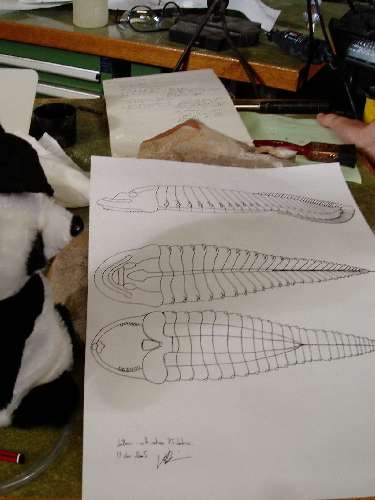

Here’s a reconstruction based on the 18 fossil impressions we have. A tadpole-like beastie similar to the chordate amphioxus. Clear muscle bands, small fin fringe, traces of what could be gill structures and a possible sensorium on the “head” area. This is pretty much what was predicted by scientists based on the finds of the primitive chordates Yunnanozoon and Pikaia in the Cambrian. Also, the Ediacaran chordate is consistent with several DNA studies which suggest that chordates arose in the Ediacaran. The main impact of this find is that the “Cambrian Explosion” is dead. Yes, there was a period of rapid diversification (if you want to call a period of 30-60 million years rapid) when animals developed hard parts. But this was preceded by a long period of time when basic body plans were developed. ID creationists claims that all animal body plans developed in an implausibly short period of time in the Cambrian are refuted by this small tadpole-like ancestor.

That’s all for now. In part 2 I will go behind the scenes at the South Australian Museum to see how these fascinating fossil critters are turned in models we can study.