Simple evolutionary study may predict path of Ebola outbreaks

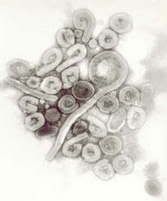

Ebola is one of my favorite pathogens. With the reputation it has, many people assume it’s killed many more worldwide than it actually has. People hear of Ebola and all kinds of grotesque images come to mind: organs “liquefying” (doesn’t really happen quite like that); bleeding from every orifice (okay, that one can be on-target); the victims dying a horrible death from a virus with an incredibly high mortality rate. There are four known subtypes of Ebola, named for their place of isolation: Ebola Reston, Ivory Coast, Sudan, and Zaire. Together with their cousin, the Marburg virus, they make up the family of viruses known as filoviruses.

Ebola is one of my favorite pathogens. With the reputation it has, many people assume it’s killed many more worldwide than it actually has. People hear of Ebola and all kinds of grotesque images come to mind: organs “liquefying” (doesn’t really happen quite like that); bleeding from every orifice (okay, that one can be on-target); the victims dying a horrible death from a virus with an incredibly high mortality rate. There are four known subtypes of Ebola, named for their place of isolation: Ebola Reston, Ivory Coast, Sudan, and Zaire. Together with their cousin, the Marburg virus, they make up the family of viruses known as filoviruses.

Marburg was the first of these to be recognized, causing an outbreak in Germany (caused by infected African research monkeys) in 1967. The Ebola Zaire strain (EBO-Z) and the Ebola Sudan strain (EBO-S) surfaced at almost the same time in 1976. The outbreak in Zaire resulted in 319 cases (90% mortality), while in Sudan, 284 cases were identified (53% mortality rate). EBO-Z then wasn’t seen for almost 20 years, re-surfacing in Gabon in 1994, and once again in Zaire (Democratic Republic of Congo) in 1995. Another EBO-Z outbreak occurred in 2001-2 in Gabon and The Republic of Congo, causing about 120 cases, 79% of them fatal. Overall, less than 2000 known human infections and 1100 deaths have resulted from Ebola since its discovery in 1976. That’s an average of 38 deaths worldwide per year over the last 29 years. Compare that to a virus such as influenza, which kills 36,000 every year in the United States alone. Or even a fairly common microbe like E. coli, which causes thousands of deaths each year due to bacterial sepsis. Worse, none of these even come close to malaria, which causes over 200 deaths worldwide every hour. The numbers make it clear that, as far as mortality goes, Ebola is small potatoes—we have more to fear from our hamburger than from this exotic African virus. Yet, the Ebola mystique lingers.