Pandas and Man at Harvard

During a break in the Dover Trial, I traveled to historic Cambridge, MA to attend the Fifteenth 1st annual Ig Nobel Prize ceremony. Visiting Cambridge allowed me to visit several friends at Harvard University, where the Ig Nobels were held. Over the years, Harvard has attracted many famous evolutionary biologists, but also many creationists. Not counting its pilgrim founders, who had no knowledge of the modern scientific method (“methodological naturalism,” as my creationist friends call it nowadays) developed in the 17th century after the puritans fled England, Harvard has been home to a few influential creationists, from Louis Agassiz in the 19th century to modern day Intelligent Design creationists. I had a chance to visit them both on this trip, and you’re welcome to join me on my travels.

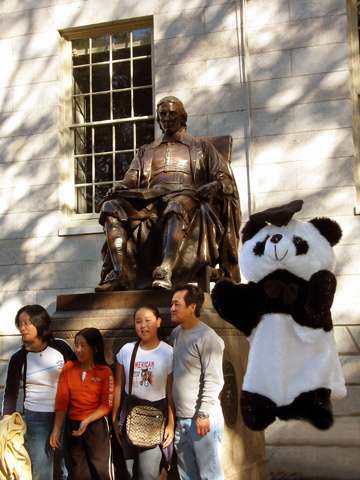

Like many of my countrymen, all trips to Harvard’s campus begin with a “pilgrimage” to John Harvard’s statue. That’s me, but that isn’t John Harvard—there aren’t any extant drawings or paintings of the eponymous Reverend Harvard, so the sculptor Daniel Chester French used as his model a handsome member of the class of 1876. If his pose looks familiar, that because French used the mirror image for his sculpture of Abraham Lincoln in the Lincoln Memorial.

Next stop: the Harvard Museum of Natural History/Museum of Comparative Zoology, my favorites! Not only is this a great museum for kids and adults, it’s actually a working research museum too, providing scholars immediate access to an immense collection of the world’s biodiversity.

The world famous Glass Flowers are also exhibited at the HMNH. These entirely glass creations by the father and son team Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka are startlingly lifelike. Nevertheless, I personally lost interest when I discovered that they did not make any glass bamboo.

James Hanken, director of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, and Elisabeth Werby, executive director of the HMNH, were very kind to escort me through their wonderful exhibits. Here is Professor Hanken with me and a specimen collected by the MCZ’s founder and first director, Louis Agassiz, in 1865. The jar contains a preserved Pterophyllum scalare (freshwater angelfish) from the Amazon, and the watercolor artwork in the background is by Agassiz’s illustrator Jacques Burkhardt. Other fascinating and priceless museum gems are highlighted in the book The Rarest of the Rare: Stories Behind the Treasures at the Harvard Museum of Natural History.

The MCZ’s fossil exhibits are unique in their diversity and scale. They seem to have as wide a range of fossil specimens as they do living species. Here I am in the jaws of a Kronosaurus queenslandicus, which lived during the Cretaceous 135 million years ago. Only the skull is visible here—this complete specimen spans the entire room!

Just two years after Darwin’s On the Origin of Species was published in 1859, “Darwin’s bulldog” T.H. Huxley initiated a controversial debate on human evolution by staking a position on the overwhelming similarities between man and apes. Today, 144 years later, Huxley’s arguments about the common ancestry of apes and humans have been confirmed by the discovery of numerous hominid fossils on several continents, and the recent sequencing of the chimpanzee genome. DNA analysis shows that human beings share about 96% of their genome with chimpanzees, the closest living species to humans. Here I am next to an exhibit of “Huxley’s skeleton group” illustrating the structural similarities between modern humans and apes that motivated Huxley.

An incorrect claim frequently made by creationists is that there aren’t transitional fossils predicted by evolution [see Creationist Claim CC200]. Au contraire! I’m standing next to a beautiful transitional sequence of horse fossils that neatly disprove this false assertion. The large horse behind me is a 3 million year old Equus simplicidens from the Pliocene, which is very similar to the modern horse. To the left is a smaller horse, a 17 million year old Parahippus from the Miocene, and to the far left is an even smaller horse, a 30 million year old Mesohippus from the Oligocene. I’m sorry that poor Mesohippus is cut off—these displays are so large that it’s difficult to capture it all. You must visit to see this sequence of transitional fossils for yourselves.

This is a portrait of the great evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr hanging in the MCZ’s Mayr Library. Mayr’s long career included both brilliant field work and theoretical studies of evolution. I highly recommend his popular book What Evolution Is, published in 2001 four years before he died at the age of 100. Another incorrect claim frequently made by creationists is that the eye is “too complex” to have evolved (see Creationist Claim CB301). Mayr directly addresses this invalid criticism (as well as a host of others) in this book:

Photosensitive, eyelike organs have developed in the animal series independently at least 40 times, and all the steps from a light-sensitive to the elaborate eyes of vertebrates, cephalopods, and insects are still found in the living species of various taxa (Fig. 10.2). They include intermediate stages and refute the claim that the gradual evolution of a complex eye is unthinkable (Salvini and Mayr 1977).

The great naturalist Louis Agassiz made his scientific career by advancing the once controversial hypothesis that a great “ice age” occurred in the past. That’s why the glacially-sculpted Matterhorn from his native Switzerland appears in this youthful portrait of him, which also hangs in the MCZ’s Mayr Library. Agassiz was a strong-willed visionary who established in 1859 with public money the very same Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard, intending to “demonstrate God’s master plan for the animals, emphasizing the individual creation of every single species.” That’s right, in 1859, the same year Darwin published his Origin, and as the 1860s wore on and Darwin’s theory of evolution came to be accepted by most scientists, Agassiz, who never gave up his creationism, insisting that species do not change over time, became isolated from the scientific community for his discredited views. Illustrating the antiquated history of Intelligent Design creationism in America, in 1868 Agassiz reported to the Massachusetts legislature that

the great object of our museums should be to exhibit the whole animal kingdom as a manifestation of the Supreme Intellect.

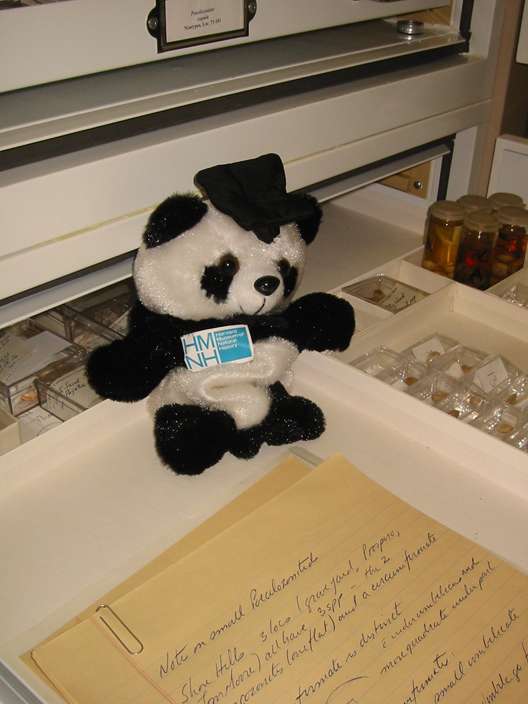

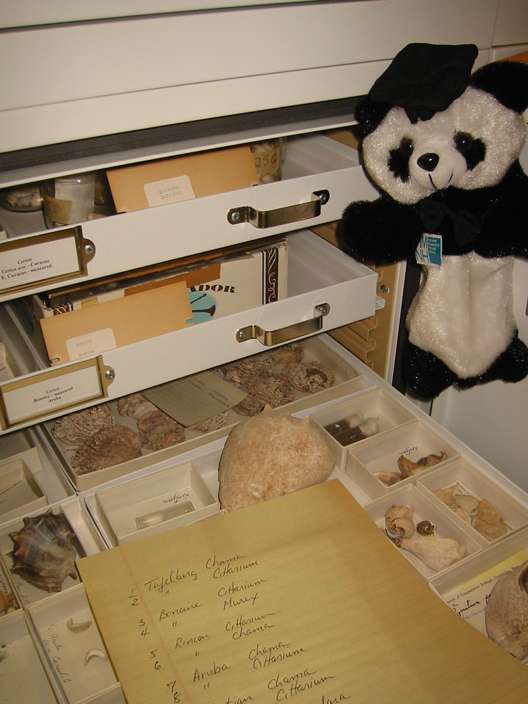

The MCZ’s basement is filled with carefully archived specimens from throughout the world. Field collections from the eminent evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould fill many large high-tech storage containers. As you may know, the NCSE’s “Project Steve” is named in his honor, not mine! People sometimes confuse that because coincidentally my first and last names are Steve too.

A zoologist friend once told me that to be happy, one should study a warm water animal. Steve appeared to have a version of this philosophy himself: these are clam fossils he collected from caves in Bermuda and Aruba. Those field notes are in his handwriting.

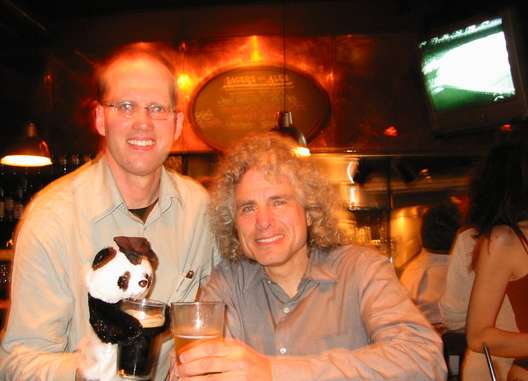

I sure build up a thirst after an afternoon at the museum! I head over to John Harvard’s Brew House to have a drink with more “Project Steve” Steves, Steven Pinker and Steven Thomas Smith. Pinker is the renowned evolutionary psychologist, who is also a member of the Luxuriant Flowing Hair Club for Scientists, which I found somewhat curious because he is in fact mostly hairless. Smith is a signal processing engineer who stumbled upon Intelligent Design creationism when a Google search uncovered information theory being hilariously misrepresented in the magazine First Things.

Did I mention that I’m a huge Sox fan? As we discussed events at the recent ID trial in Dover, PA and goings on at Harvard’s campus, we also cheered on my favorite baseball team’s playoff bid. Unfortunately, the dynasty must wait until next year.

Next evening, the Ig Nobel prizes, which every year “honor” outstanding accomplishments that cannot or should not be reproduced. In 1999 the Kansas School Board received an Ig Nobel prize in Science Education

for mandating that children should not believe in Darwin’s theory of evolution any more than they believe in Newton’s theory of gravitation, Faraday’s and Maxwell’s theory of electromagnetism, or Pasteur’s theory that germs cause disease.

Though scientific facts like evolution and religious faith are not necessarily incompatible, science does discredit some religious beliefs, like creationism, and supports others like the essential equality of all human beings, as well as “the discovery that black holes fulfill all the technical requirements to be the location of hell,” as recognized by the 2001 Ig Nobel prize in astrophysics.

My favorite occurrence this year wasn’t a prize, it was the fact that Harvard professor Roy Glauber, the Ig Nobel’s official stage sweeper (much paper debris must be removed throughout the event) could not fulfill his sweeping duties this year because he was in Sweden accepting his own Nobel Prize in physics this year. Really.

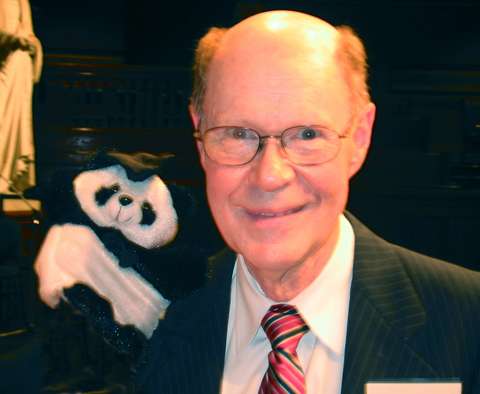

In addition to sweepers, the Ig Nobel ceremony includes many real Nobel laureates as “authority figures” and dignitaries, including Robert Wilson, the co-discoverer of the Big Bang’s cosmic microwave radiation, for which he received his Nobel Prize in Physics (1978). I’m shown standing here with Professor Wilson, who wishes me good luck ridiculing the Intelligent Design creationists. Amazingly, many creationists also deny the Big Bang. Now admittedly evolution is perhaps more difficult to visualize, occurring as it does over large populations and long time scales, but you can look at a picture of the Big Bang, taken by NASA’s Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe in 2003.

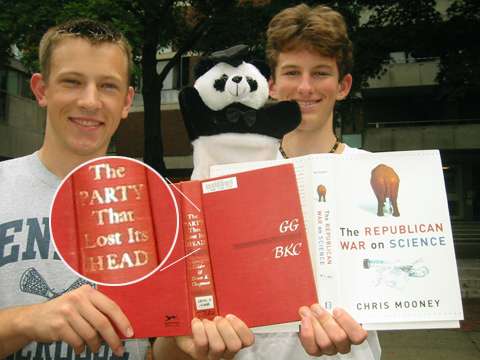

One last stop before I must depart. In his book The Republican War on Science, Chris Mooney reveals that George Gilder ‘61/62 and Bruce K. Chapman ‘62 of the Discovery Institute had been roommates at Harvard College. A few years after they graduated, they published the prescient book of political analysis The Party That Lost Its Head, wherein they warn:

In recent years, the Republicans as a party have been alienating intellectuals deliberately, as a matter of taste and strategy.

I’m visiting the Quincy House yard where Gilder and Chapman resided together as undergraduates before they fell victim to the very warning they delivered almost 40 years ago. I’d like to thank Quincy House residents Tom Wooten ‘08 and Zach Widbin ‘08 for helping me hold up these weighty tomes, which are much too heavy for my feeble thumbs. Pondering the example of their forebears Gilder and Chapman, who knows what addle-headed nonsense these two bright sophomores will burden our country with when they make their own way in the world?

I’m off! Next time I return, I hope to explore the compelling evidence for ID at Harvard Medical School’s Warren Anatomical Museum. Until then, you may examine this intelligently designed hand from their extraordinarily unique collection.