Down with phyla! (episode II)

Note: The paper by Chen et al. is now published online. Embarassingly for the BBC, the fossil is named_Vetusto_v_ermis, not_Vetusto_d_ermis_. I thought the misspelling would explain why_Vetustodermis_originally got zero google hits (there are now 160 google hits on_Vetustodermis_), but it turns out that_Vetustovermis_currently gets zero google hits, although I am sure this won’t last. Anyhow, I will correct the name, and add a few comments on the paper to the end of this post._

The BBC has a story up about the Cambrian fossil Vetustovermis planus, a critter so obscure that, at the time of this posting, it received zero hits on google. The BBC reports that a study is coming out in the Proceedings of the Royal Society, Series B: Biological Sciences that evidently phylogenetically places Vetustovermis outside of any extant phylum, but perhaps nearer to molluscs within the Lophotrocozoans.

The question raised by the BBC story and also by Charles Alt at the Philosophy of Biology blog is whether or not this kind of critter deserves a whole new phylum of its own. If you accept the premise that every fossil must be put in some phylum, and if a fossil doesn’t fit within the definition of known phyla then you should invent a new phylum, then the answer is clearly “yes.” However, as I argued in my previous post “Down with phyla!”, Cambrian paleontologists are abandoning this convention, because it artificially elevates objectively moderate character differences into the subjectively “big” “phylum-level differences”. Another way to say this is that inventing new phyla for fossils has the effect of converting the true pattern of evolution, which is a thoroughly fractal branching tree, into a “phylogenetic lawn of phyla” pattern, which is very misleading.

The question raised by the BBC story and also by Charles Alt at the Philosophy of Biology blog is whether or not this kind of critter deserves a whole new phylum of its own. If you accept the premise that every fossil must be put in some phylum, and if a fossil doesn’t fit within the definition of known phyla then you should invent a new phylum, then the answer is clearly “yes.” However, as I argued in my previous post “Down with phyla!”, Cambrian paleontologists are abandoning this convention, because it artificially elevates objectively moderate character differences into the subjectively “big” “phylum-level differences”. Another way to say this is that inventing new phyla for fossils has the effect of converting the true pattern of evolution, which is a thoroughly fractal branching tree, into a “phylogenetic lawn of phyla” pattern, which is very misleading.

This change in thinking is the subtext underlying the comments of the scientists quoted in the BBC article. David Bottjer provides the pro-phylum quote that the reporter used, but he sounds somewhat noncommittal. Jonathan Todd, on the other hand, appears to have attempted to give the reporter the basic down-with-phyla debate, and whether or not the reporter “got it”, at least some of it made it into the article:

However, Dr Todd is reluctant to create a whole new phylum to accommodate Vetustovermis; that, he thinks, would be premature.

“Some scientists have thought that there were so many distinct phyla in the Cambrian,” he said. “They came to that conclusion because they were not thinking in the phylogenetic sense, they were thinking ‘hey, that is a unique set of features – it must be a distinct phylum’.”

So rather than creating new phyla every time something doesn’t fit an existing one, the really interesting exercise, Dr Todd thinks, is to establish just how Vetustovermis slotted into the greater evolutionary tree.

If, indeed, it did belong to a different phylum, how did that group connect to the molluscs, annelids and arthropods?

“We don’t really know the phylo-genetic relationships between the extant phyla,” he said. “Molecular genetics has only gone so far. But recent phyla have got to connect somehow. These fossils really offer the opportunity to tie together recent phyla.”

For that last paragraph, I will take the liberty of translating what the reporter wrote down into what Jonathan Todd probably thought he was saying:

“We don’t really know the phylogenetic relationships between the extant phyla,” he said. “Molecular genetics has only gone so far. But Recent phyla have got to connect somehow. These fossils really offer the opportunity to tie together Recent phyla.”

Here’s the take home message in my view: these ambiguous Cambrian fossils belong to stem groups that diverged before the last common ancestor of the currently-living (“Recent”) members of a phylum. They thus have some, but not all, of the characters that living members of a phylum have in common. These ambiguous fossils, therefore, are exactly the ones that are going to show us how the character suites of living phyla were gradually acquired in the stem groups. We shouldn’t be shoehorning these fossils into the typological categories of either extant phyla or newly-invented phyla, when the thing we want to study is the fundamentally non-typological process of evolutionary transition.

Additional commentary now that the paper is published: As I indicated, the stuff about “new phylum” was mostly hype. The terms “phylum” or “phyla” do not appear in the paper.

The paper does not contain a cladistic analysis – the clear characters that are available are very limited. The paper, which is only 5 pages long, does contain a cursory exploration of the possible affinities of Vetustovermis. I will quote this below, and intersperse a few comments, and links to the more obscure groups. For me, the take-home message is that the known basal groups and sister groups of the “advanced” phyla (arthropods, chordates, molluscs, echinoderms, etc.) are all pretty much soft-bodied worms and slugs. Not many characters are going to be preserved in worm fossils. It therefore shouldn’t be that surprising that certain wormlike/sluglike Cambrian forms are hard to lump with the modern phyla.

3. LIFE STYLE AND PHYLOGENETIC IMPLICATIONS

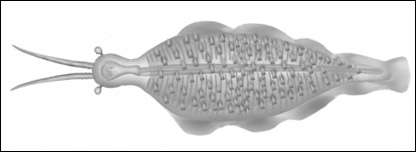

The flattened body and horizontal fins of Vetustovermis planus could have been an adaptation to support the animal as it moved on the soft seafloor, as well as for gliding or swimming near the seafloor. The large surface area of the gills may have provided effective gas exchange for an active life style. The well developed sense organs including a pair of large, stalked eyes and large cephalic tentacles suggest that Vetustovermis planus was attuned to the presence of food resources as well as possible predators.

Vetustovermis planus resembles molluscs by having a flat foot, a polyplacophoran-like flexible elongated body, and serial pairs of gills on each side of the trunk (Brusca & Brusca 2002). The dorsal conic spine-like structures could be a homology of cuticular spicules of polyplacophorans and aplacophorans. This variety of characters is not specific to any crown group of molluscs (Brusca & Brusca 2002). The head has paired tentacles and stalked, basal eyes. Despite a number of conchiferans also having such a well differentiated head, this character probably was absent among more primitive molluscs. Thus, the character of a sluggish head yields no strong implication of a molluscan affinity. The gills in Vetustovermis are also simply bar-shaped and different from molluscan gills, thereby giving only weak support for a molluscan affinity.

Polyplacophorans are chitons, early-diverging molluscs that exhibit some segmentation.

Conchiferans are “all molluscs except chitons and aplacophorans” – i.e. snails, cephalopods, etc. They have a single shell (lost in many groups) and shell-making glands.

Although arthropods and annelids can also have stalked eyes and tentacles, they lack the ventral foot, instead using leg-like appendages for locomotion. Thus, the foot is the best evidence for lack of an arthropod or annelid affinity. One might argue that the axial band-like visceral cavity of Vetustovermis planus is a notochord and that the transverse bars are not gills but myomeres, thereby indicating this animal was a chordate. However, no known chordate has stalked eyes or a ventral foot.

Vetustovermis planus resembles some planktonic nemertines, especially Nectonemertes and Balaenanemertes, in several respects (Gibson 1972; Hyman 1951). These include an anterior tentacle, lateral fins, ventral foot and a series of internal gut caecae comparable to the ‘gill’ of Vetustovermis planus. Nemertines however, lack a protective cuticle or exoskeleton as well as stalked eyes, but have a characteristic eversible proboscis. Presence of spine-like protective structures and stalked eyes and absence of a proboscis do not support a nemertine affinity for this animal.

Whaaaa? The last I heard, Pikaia was considered a basal chordate with stalked eyes:

The ventral flat foot also represents a trait that is shared with many turbellarians (free living flatworms) (Hyman 1951; Ruppert et al. 2004). The combined existence of a head, and elaborated paired tentacles and stalked eyes gives no support for an affinity of this animal to flatworms. Some polychaetes such as the sea mouse (Aphrodite aculeate) also bear a ventral muscular, creeping sole; myzostomids have a circular body with fused parapodia, which also forms a ventral foot like structure. However, the sea mouse is covered with a thick felt-like or hair layer, and myzostomids have numerous extended cirri (Rouse & Fleijel 2001; Ruppert et al. 2004).

Ancestral molluscs are widely accepted to have lacked a mineralized shell. Trace fossils that suggest grazing with a radula (Radulichnus) (Erwin & Davidson 2002; Seilacher 1999, 2003), together with large imprints of possible molluscs lacking a mineralized shell (Kimberella) from the latest Neoproterozoic (Erwin & Davidson 2002; Fedonkin & Waggoner 1997; Seilacher 1999, 2003), imply that macroscopic molluscs have a deeper evolutionary history. Vetustovermis bears a number of morphological features that are found in Kimberella, which has been interpreted to have a non-mineralized but stiff univalve shell. Like Vetustovermis, Kimberella has many structures (crenellations) that may have been gills, has a broad flat foot, showing metamerism, and its shell bears many impressions, which may be the remains of sclerites or spicules.

Vetustovermis shows a similarity with shell-less sea slugs, which are gastropods that evolved from the shelled ancestors (Yonge 1960). The similarity is thus superficial, as a result of convergent evolution.

In summary, some characters as mentioned may indicate a possible molluscan affinity of Vetustovermis. These characters, however, are found separately within different molluscan groups. For instance, an elaborated head and eyes did not occur in primitive molluscs before the level of Conchifera; serial pairs of gills are seen only in the Polyplacophora and Tryblidia; and an oval foot is known in Tryblidia, polyplacophorans and archaeogastropods only (Brusca & Brusca 2002; Ruppert et al. 2004). A molluscan affinity for this animal, therefore, is poorly grounded. These soft-bodied animals with the characters described here could represent an independently evolved animal lying outside of molluscs. Similar animals have also been recorded from Middle Cambrian Burgess Shale. Several Burgess Shale problematic creatures, including Nectocaris (Conway Morris 1976), Amiskwia (Walcott 1911), and Odontogriphus (Conway Morris 1976), are likely candidates for interpretation as Vetustovermis-like soft-bodied animals. Although the single specimen of Nectocaris has been viewed as laterally compacted, we suspect that it is a subdorsally compacted specimen. If this alternative interpretation is correct, the resemblance with Vetustovermis is thus striking by sharing a number of features including a slug-like head that carries a pair of cephalic tentacles and stalked eyes, a trunk that was laterally finned with a triangular anterior portion, and a large number of transverse gills spread over most of the trunk. Amiskwia also shares a number of features with Vetustovermis planus. They include a flat body with a slug-like head and lateral and posterior fins on the trunk. Although the gross morphology of Odontogriphus appears significantly different from Vetustovermis planus, its potential affinity with Vetustovermis is suggested by its dorso-ventrally flattened body and series of transverse lines on the trunk (comparable to the gills of Vetustovermis).

Vetustovermis planus resembles the Carboniferous problematic Tullimonstrum gregarium in several important respects (Foester 1979). These include a dorso-ventrally flat trunk, lateral fins, a distinct visceral mass, stalked eyes, and a series of transverse segments. Foester has tentatively interpreted Tullimonstrum gregarium as a prosobranch gastropod (Conway Morris 1976).