Dembski on Human Origins, reprise

William Dembski has posted a revised version of his essay on human origins on www.designinference.com. This was way back in August, but I’ve been busy. In the acknowledgements he thanks me, amongst others, for helpful criticism. Now I’m quite chuffed that I could help the greatest philosopher of our time with his essay, but it might have been nicer if he actually had acted on my criticisms.

As before, there are still numerous biological mistakes Dembski makes in this essay. He didn’t take my advice to get a real biologist to look over it carefully. What about my specific criticisms?

Dembski wrote in version 1 Consider, further, that chimpanzees (like the other apes) have 48 chromosomes whereas humans have only 46 chromosomes. . .

Now, this is presumably meant to throw doubt on the 98% figure, because humans have lost a pair of chromosomes compared to chimps. But we have 46 chromosomes because two chromosomes that are separate in chimpanzees are fused in humans. This doesn’t affect the similarity of our DNA one bit. However, Dembski still has this section word for word in version 2.

Next, after a far too long section of alternate versions of a Hamlet soliloquy, he made this remarkable statement.

Dembski wrote in version 1 The similarity between human and chimpanzee DNA is nothing like the similarity between these two versions of Hamlet’s soliloquy. With the two versions of Hamlet’s soliloquy, we’ve lined up the entire texts sequentially. By contrast, when molecular biologists line up human and chimpanzee DNA, they are matching arbitrarily chosen segments of DNA. It’s like going through the works of William Shakespeare and John Milton, and finding that 98 percent of the words and short phrases they used can be lined up letter for letter and therefore are the same.

He has now changed it to this:

Dembski wrote in version 2 The similarity between human and chimpanzee DNA is nothing like the similarity between these two versions of Hamlet’s soliloquy. This is because of the complex ways that genetic information is utilized within cells. Biological function can depend crucially upon extremely small changes in proteins as well as in how they are utilized over time and in space. The way proteins interact forms a higher order network that is not visible from nucleotide or amino-acid sequences alone and thus is opaque to sequence analyses. It’s like going through the works of William Shakespeare and John Milton, and finding that almost all the words and short phrases they used are identical.

This is marginally better; at least he’s got rid of the “arbitrarily chosen sequences”. Unfortunately for Dembski, he’s still wrong. As I pointed out, the chimp-human sequence similarity is like comparing his two versions of Hamlet. It’s not just words or short phrases the same, it’s entire chapters the same with the occasional spelling mistake. We have not only virtually the same genes, but they are virtually in the same order and location in the genome and chromosomes.

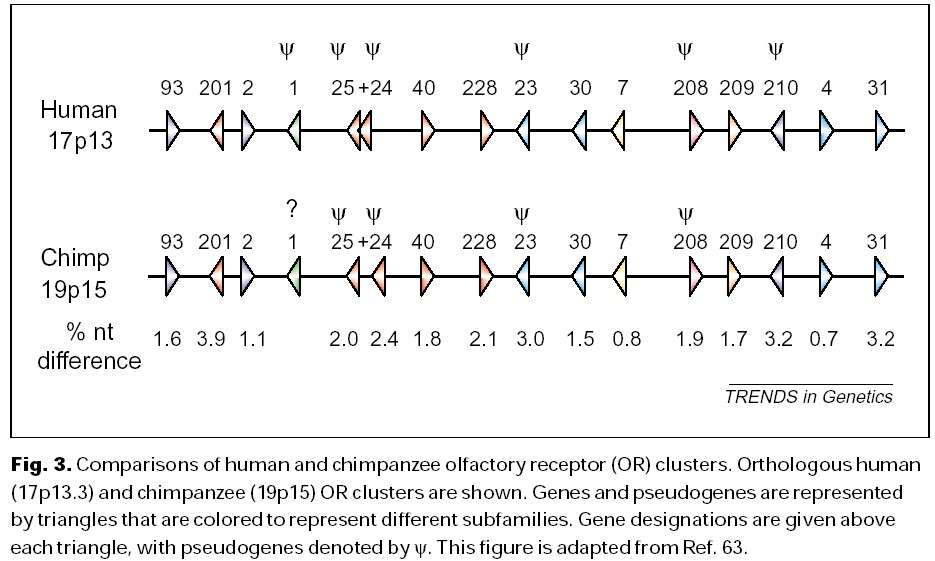

Figure, order of olfactory genes in the chimpanzee and human, taken from TRENDS in Genetics Vol.17 No.11 November 2001 See also this list of genes and gene locations on chromosome 22 comparing chimp and human chromosomes. See also this online book for more about gene organization in chimps and humans.

Note the new section in the middle about how small changes can have large functional effects. This is not in dispute, and is the standard explanation from evolutionary biology of why organisms with very similar genes can have large phenotypic differences. However, Dembski seems to think that this is a point against chimpanzees and humans being related by common descent. On the contrary, these show how humans and chimps can be related but have substantial phenotypic differences.

Remember, the whole point of Dembski’s paper is to show the alleged inadequacy of our reasons for inferring common descent, and to show in this instance having a very similar genome doesn’t mean that chimps and humans are related. Now, remember that genes are passed on from ancestor to descendent via imperfect copying.

My brother’s DNA is more similar to mine than my cousin Jeff’s, as my brother and I share a more recent common ancestor (parents) than Jeff and I (grand parents). Similarly Jeff and I have more similar DNA than someone from South Australia named Musgrave as the South Australian Musgrave last shared a common ancestor with us (Great great great great . . .great grandparents) around the time the Musgraves helped to chase Young Lochinvar. The South Australian Musgrave’s and I have more similar DNA than a Frenchman named Falkner, as we last shared a common ancestor around the time of the Norman invasion (Musgraves and Falkners were both Falconers). The Falkners and I have more similar DNA than Ötze the iceman, as we last shared a common ancestor somewhere in the Bronze age. And so on into the past.

We know, from theory, from experimental phylogenies and observation of evolving organisms that closely related organisms have more similar genomes that distantly related ones. This is the very basis of paternity testing and forensic gene tests to determine if otherwise unidentifiable bodies are related to particular people (the identity of the suicide bomber who attacked the Australian Embassy in Jakarta was found this way).

So the inference of common ancestry from gene similarity is not an airy-fairy idea plucked out of the air by evolutionary biologists to bolster their theories. Ironically, given Dembski’s Hamlet example, we use the shared patterns of copying errors in manuscripts to determine which master manuscripts they were copied from. The fact that genes form complex regulatory networks that can’t be invoked from sequence alone is irrelevant to the inference of common descent, it is the sequence that matters.

Unfortunately for Dembski, not only is the chimpanzee genome close to humans in overall nucleotide sequence, coding gene sequence, gene organization and genome organization, it is closer to us than any other organism (excepting the chimpanzee sister species, the pygmy chimp or bonobo which is 99.7% similar). The sequences of other great apes form a nested hierarchy of relatedness, with chimps/bonobos and humans closest, followed by Gorillas, followed by Orang-utans, followed by Old world Monkeys. In fact, the genomes of chimps and humans are closer than many other close species pairs. Heck, humans and chimps are closer than pairs of naked mole rat species living across a valley from each other. If you accept that a pair of naked mole rat species descend from a common ancestor, then you would be hard pressed to deny that humans and chimps share a common ancestor based on the same evidence.

One thing Dembski does is try to show that chimps and humans are further apart than we think and imply that this means that we do not share a common ancestor. Most modern studies (which Dembski largely ignores) compare sequences for similarity nucleotide by nucleotide. Where there are insertions or deletions, they are ignored in these comparisons, as how do you score the similarity of something that is missing? A study by Britten did try to account for these gaps. Using Britten’s measure, chimps and humans have 95% similarity. This is still impressive similarity by any means. Demski cites Britten’s study as if throws doubt on common descent. However, using Britten’s measure humans and chimps/bonobos are still very close, and still closer than any other organism, and you still get the branching hierarchy of relatedness seen with the “nucleotide by nucleotide” method. One feature of accounting for insertions and deletions (indels) is that they overemphasize differences caused by loss of blocks of “junk” DNA.

It may surprise you, but DNA that codes for protein or functional RNA’s such as ribosomal RNA only comprises between 1.5-2% of the DNA in our genes. Between 2-5% of DNA are regulatory sequences, that guide how and when protein-coding genes are turn on. About 2-5% of the genome is broken copies of genes, and about the same amount is broken viruses. The vast majority of DNA has no known function (it has been suggested that some of this DNA forms a kind of scaffold for the chromosome). Puffer fish do quite well with 50% less non-coding DNA than the rest of us, and in experiments where huge chunks of this non-coding DNA have been removed from mice, they live on quite happily. About 40% of this non coding “junk” consists of blocks of highly repetitive sequences, some are long, some are short.

If the protein coding sequences are equivalent to “Hamlet”, then the repetitive sequences are equivalent to “doobedoobedoobe” or swatches of pages with “this page left intentionally blank” on them. Because the repetitive sequences occur as blocks, insertion or deletion of these blocks cause a larger apparent difference between sequences, even when there has only been one insertion event. Nonetheless, the insertion and deletion of these repetitive elements also can give us clues to common ancestry.

Again, the pattern of insertions and deletions shown humans and chimps closer than any other group, and form a nested hierarchy that parallels the ones from “nucleotide by nucleotide” comparison. Dembski, and many other evolution deniers, use an argument that since chimps and humans look similar, it’s not surprising their genes look similar. The fact that the non-functional DNA gives the same pattern of similarity that we get from gene similarity is telling.

Dembski notes that the chimp choromosme 22 sequencing group, who found that chimp chromosome 22 was 98.6% identical to it’s human counterpart, “were surprised to find 68,000 insertion and deletion”. Well, if you look at the paper, they weren’t surprised, they expected quite a few. 68,000 insertions and deletions add about another 1% difference, so the chimp chromosome 22 is roughly 97.6% similar to its human chromosome equivalent when indels are accounted for. Indels affect junk more than genes, so you see less of an effect on gene similarity compared to genome similarity. Again, even if you account for indels you still get the nested hierarchy, with humans closer to chimps than any other animal.

| "Chimp" sequence | "Human" sequence |

|---|---|

| Dobee Dobee Dobee Dobee Dobee Dobee Dobee Dobee What is a man, If his chief goid and market of his time Be but to sleep and feed? abeast, no more. Sure, he that made us with such large discourse, Looking befure and after, gave us not That capabilility and god-like reason To fust in us unused. Dobee Dobee Dobee Dobee Dobee Dobee Dobee Dobee Dobee Dobee Dobee Dobee Dobee Dobee Dobee Dobee | Dobee Dobee Dobee Dobee Dobee Dobee Dobee Dobee What is a man, If his chief good and morket of his time Be but to sleep and feed? a beast, no more. Sure, he that made us with such large discourse, Looking before and after, gave us not That capabililility and god-like riason To fust in us unused. Dobee Dobee Dobee Dobee Dobee Dobee Dobee Dobee Dobee Dobee Dobee Dobee Dobee Dobee Dobee |

Returning to Hamlet, the comparison above is a version of Hamlet as if it were part of the human or chimp genome. For simplicity I’ve ignored introns, but added in some of the repetitive sequences that make up over 46% of our genome (something that really represented our genome would look more like DobeeDobeeDobeeDobeespacerspacer{start}wh{remove}at{end} spacerspace{start}i{remove}s{end}spacerspacerspacer{start}a{end} spacerspacerspacer{star}ma{remove}n{end} and be totally unreadable). I’ve used a 5% difference between the two “genomes”, with indels as well as replacements. Now, even with indels it is clear that the “chimp” and “human” sequences are likely imperfect copies of a single manuscript, rather than the human one being independently authored by Milton.

Dembski makes much of the fact that the expression of chimpanzee genes differs from that of humans. However, this is what we expect. Evolutionary biologists have been saying for decades that the main differences between humans and chimps will lie in changes in the timing and levels of expression of genes, not in differences in the genes themselves. For example, we differ from adult chimps in the angle of our facial features and placement of the skulls connection with the spinal chord. However, we are very similar to young chimps in this feature, and it has been long suggestion that changes in the timing of development pathways of the chimp/human common ancestor could give us our flatter faces.

While humans and chimps do differ in gene expression, they only roughly 1% of their genes have different gene expression levels, so their overall patterns of expression are quite similar. What’s worse for Dembski is that you can construct a tree of relatedness with gene expression just as you can for gene sequences. Guess what, gene expression produces the same nested hierarchy of relatedness, with chimps our closest relatives, as we find for genes.

So we can see that:

- Overall gene structure and gene location and order are most similar between chimps and humans

- Gene sequences are most similar between humans and chimps

- “Junk” DNA sequences (and indels) are most similar between humans and chimps

- Patterns of gene expression are most similar between humans and chimps

By all measures humans and chimps/bonobos are closer than any other organism, and by all measures human and chimps form part of a hierarchy of relatedness with great apes closest to us. All the hierarchies are congruent, which is exactly what we expect if this hierarchy is due to inheritance of DNA from a common ancestor. Furthermore, the genetic differences between humans and chimps are less than many species that evolution-deniers are happy to accept as having “microevolved”.

Dembski often uses his critics to patch up problems in his arguments. However, if he is sincere in this he should look carefully at the criticisms. As it is, Dembski has either ignored the substance of the criticism and deleted outrageously wrong material but left incorrect arguments intact, or incorporated material that actually undermines his point. Perhaps, if he actually looked at the data and tried to understand it, he would see why the inference of common descent is so strong.