Simulating the early evolution of plants

An excellent review paper discussing the evolution of evolutionary theory is:

Ulrich Kutschera · Karl J. Niklas The modern theory of biological evolution: an expanded synthesis Naturwissenschaften (2004) 91:255-276

While the paper has some very interesting things to say, I will focus on a more narrow issue namely the success of Darwinian simulations of early plant evolution by Karl Niklas. For this we need to go back in time 400 Million years (Ma) to the early Devonian and look at the evolution of ancient vascular plants.

AccessExcellence has an outstanding Tutorial by Karl Niklas which I will use to clarify some of the issues.

I encourage the reader to first read the Tutorial and then return here.

See also the PBS Website

As a final note, I will compare Niklas’s findings with some of the claims by ID proponents, largely based on TRIZ that Darwinian evolution cannot be inventive.

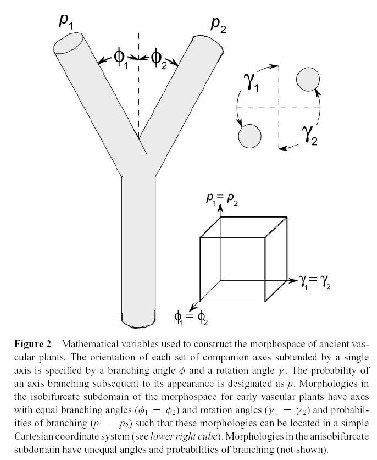

Niklas used computer models to mimic the early evolution of tracheophytes (ancient vascular plants). The architecture of the early spore producing tracheophytes can be mathematically simulated using relatively few parameters such as axial length, diameter, probability of branching, angle of branching, and the rotation angle. These parameters define the possible morphological variants or morphospace. In addition four very basic functions applicable to all plants can be defined. Namely interception of sunlight, exchange of water and gases and waste, stability, and reproduction. The fitness of these four functions can be evaluated rigorously using concepts of physics and chemistry.

The model has three components

- an N-dimensional domain of all mathematically conceivable ancient morphologies (the morphospace for ancient tracheophytes);

- a numerical assessment of the ability (fitness) of each morphology to intercept light, maintain mechanical stability, conserve water, and produce and disperse spores

- an algorithm that searches the morphospace for successively more fit variants (an adaptive walk).

1. Morphological space

The morphospace, or the multidimensional domain of all mathematically achievable morphologies is determined by a set of parameters and the probabilities assigned to their values. The total number of possibilities is determined by the range of the parameters involved and their increments.

2. Fitness

Niklas looked at four biological tasks:

- Light interception

- Mechanical support

- Hydraulics

- Reproduction

Let’s start out with an example of a small spherical cell (the universe of morphologies include shape, size and geometry). How would the shape and geometry of a cell have to change to accomodate two important biological functions. The first function is interception of light, the second is maximization of the surface versus the volume. Light interception is important since plants rely on photosynthesis. The ration of surface versus volume is important since volume of a cell sets its metabolic requirements, while the surface determines how efficiently a cell can absord material and excrete waste to the environment.

2a. Light interception

The ability to intercept sunlight depends on the size, geometry and frequency of light. For spherical cells the ability to intercept light decreases when its size increases. These data suggest that there is an advantage for remaining small and how geometry may change when size increases from spherical to for instance cylindrical.

Niklas shows how predicted and actual observations coincide nicely. When cells increase in size, they change shape and geometry.

Light interception can be quantified in terms of the surface area projected towards the sun, and how this projection varies as function of time, latitude or seaon.

2b. Mechanic stability

Mechanic stability can be quantified in engineering terms of stability, strength, flexibility etc.

2c. Spore dispersal

Spore dispersal can be modeled using simple aerodynamic principles.

2d. Exchange of water

Exchance of water and other necessary gasses can be quantified in terms of the ratio of surface area to volume and fluid dynamic equations.

It should be obvious by now that evolution has to deal with many contradictory requirements.

3. Adaptive walk

Each walk begins at the same location, which corresponds to the morphology of the most ancient vascular plant. From here the algorithm evaluates the fitness of all its neighbors. If one or more neighbors has a higher fitness, the walk moves to their locations in morpho-space.

The simulations

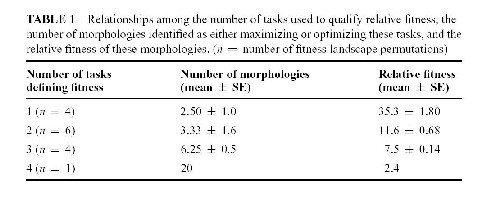

On stable landscapes, there are comparatively few morphologies capable of maximizing the performance of any of the four functions. However, when the number of functions to optimize increases, the number of optimal morphologies increases. In addition, the global fitness of these multiple morphologies decreases. This suggests that evolution may proceed easier when it has to optimize for multiple functions.

All four tasks can be rigorously quantified using principles of physics and chemistry. This is important because we can now look at a particular morphology and, using small increments, explore the fitness landscape. Niklas found something very interesting:

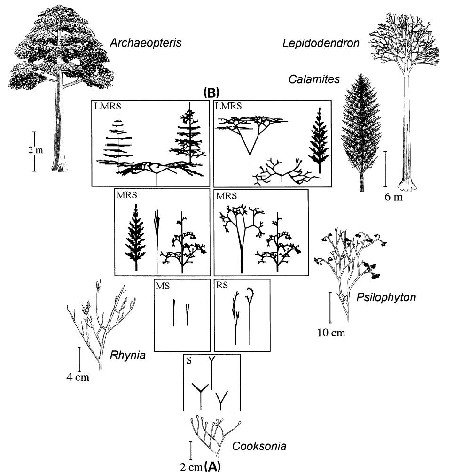

Beginning with one of the most ancient plant forms (Cooksonia, Early Devonian; see Fig. 6A), tracheophyte evolution is simulated by locating neighboring morphologies that progressively perform one or more tasks more efficiently. The resulting “adaptive walks” indicate that early tracheophyte evolution likely involved optimizing the performance of many tasks simultaneously rather than maximizing the performance of one or only a few tasks individually, and that the requirement for optimization accelerated the tempo of morphological evolution in the Mesozoic (from the Early Devonian to the late Carboniferous; see Fig. 6A).

For the next discussion please look at the figures on this page at the Access Excellence website. You can click on the pictures and a larger picture will pop-up.

Evolution using only one function

A/R (spores/reproduction), L (light interception), S (water conservation), M (mechanical stability)

Improvement in reproductive function leads to tall plants, improvements in light interception function to tall wide plants, while water conservation leads to small plants with few branches and finally stability leads to tall but narrow plants.

Evolution using two functions

We see how the combination of two functions leads to more interesting morphologies.

Evolution using three and four functions

The trend to see more and more morphologies and morphologies which seem to mimick real plants continues when adding additional functions.

A comparison of the fossil plants depicted in Fig. 6A that evolved over a period of 100 Ma and the “digital organisms” (Fig. 6B) reveals a striking similarity in form and design.

Niklas points out that addition of more and more functions leads to a need to distinguish between maximization and optimization and “to the fact that natural selection acts on the phenotype as a whole and not on its individual parts (Mayr 2001). Every organism must perform a wide range of biological functions to grow, survive, and reproduce. No single function is more important than any other, because the phenotype is an integrated functional whole and because environmental factors influencing one or more parts of the phenotype indirectly or directly affect the whole organism.”

Niklas concludes with:

Importantly, different biological tasks have different phenotypic requirements and some tasks have antagonistic design requirements. Therefore, although it is possible to maximize the performance of one task, this maximization comes at some expense in terms of performing other tasks.

Fig. 6A, B Reconstruction of the evolution of land plants (tracheophytes) based on the fossil record (A): Cooksonia, Rhynia and Psilophyton from the Early Devonian (~400 Ma ago), Archaeopteris from the Late Devonian (~350 Ma), Calamites and Lepidodendron from the Late Carboniferous (~300 Ma ago). Computer simulation of early vascular land plant evolution (B). The virtual organisms were maximised for water conservation (S), mechnical stability (M), reproductive efficiency (R), and light interception (L) (stages 1-4). The fossils (A) and the digital plants (B) are very similar. (Adapted from Niklas 1992, 2000b)

The earliest vascular plants, the Cocksonia are very similar to morphologies which arise under optimization of a single function namely water conservation. The walk then bifurcates into water conservation and mechanical stability and water conservation and spore dispersal. The next step is a 3 task landscape of water conservation, mechanical stability and spore dispersal. Finally a 4 task landscape includes light interception.

Niklas comments

These two simulations illustrate an important feature, which resurfaces in all similar walks through unstable landscapes. Even though adaptive walks enter the same fitness landscape, they locate different morphological optima depending on how relative fitness was defined in previous portions of walks

Reaching the very important conclusion

If there is a lesson to be learned, it is that we should not expect the mechanisms of adaptive evolution to achieve the best conceivable morphologies but rather only those that are the best relative to what is available based on past history.

Side step: TRIZ

Dembski, Bracht and other ID proponents have used TRIZ to suggest that evolution may be uncapable of inventive solutions. One of the main foundations of TRIZ is the existence of contradicting requirements.

Dembski in ID as a Theory of Technological Evolution writes

TRIZ seeks to resolve these contradictions not so much by balancing advantages against disadvantages, as in constrained optimization, but by novel win-win solutions that maximize useful functions without (ideally) incurring harmful side-effects.

But this is exactly what evolution does quite effectively.

Dembski, who is not a biologist, concludes surprisingly

Sudden innovation, convergence to ideality, and extinction are all part of TRIZ?s evolutionary scheme. Now where have we seen that scheme before? The scheme is non-Darwinian. Nor can the Darwinian scheme be easily modified to accommodate it.

Sudden innovation and extinction are hardly non-Darwinian although I can understand why some less familiar with evolutionary theory may reach such a conclusion. Convergent evolution also is hardly non-Darwinian.

And then Dembski states

TRIZ’s evolutionary scheme fits quite nicely with Eldredge and Gould’s model of punctuated equilibria.24 Leaving aside their model’s mechanism of evolutionary change and innovation, the patterns of evolution described by TRIZ and the Eldredge-Gould model are quite similar.[/url]

So on one hand TRIZ evolution is non-Darwinian but on the other hand they fit nicely with Punctuated Equilibria. It’s sad that despite all the writings on this topic, people still seem to be confused about Puncatuated equilibria and Darwinism.

Dembski concludes

[quote] What’s more, thanks to TRIZ, a ready-made theory of technological evolution is already in place to interpret biological evolution. Biology confirms the patterns of technological evolution outlined by TRIZ. Significantly, these patterns are non-Darwinian.

Sigh…

Dembski, W.A., Becoming a disciplined science: prospects, pitfalls, and a reality check for ID.

Dembski, W.A., ID as a theory of technological evolution.

Bracht Inventions, Algorithms, and Biological Design

It has become evident that large changes and radical re-designs, which require re-working the hypervolume of possibilities, are off-limits to the Darwinian process, but we may expect organisms that differ only slightly, and co-exist within the same hypervolume, to evolve into each other.

Actually such re-working of the hypervolume of possibilities are NOT off limits to Darwinian evolution. Neither are large changes or radical re-designs. Gene duplication and divergence can lead to increased hypervolumes. And large changes refer to phenotype changes not to genotype changes.

An ISCID discussion. But I digress.

Let’s have a look at how TRIZ and evolution do map quite nicely:

Systematic technology transfer from biology to engineering By Julian F. V. Vincent and Darrell L.

The tools of TRIZ

The method uses four main tools: a knowledge database arranged by function, analysis of the technical barriers to progress (contradictions), the way technology develops (ideality) and the maximization of resource usage.

Contradiction

In TRIZ, problems are represented by pairs of conflicting parameters enabling us to access the good solutions of inventors who have successfully overcome the contraict in question.

Ideality

In analysing the patent database, TRIZ researchers have shown that technical systems evolve in predictable ways, most notably an over-riding trend to increasing ‘ideality’ (Kowalick 1997). This is very much like biological adaptation in that technology develops towards systems which maximize the good (functional benefits) and minimize the bad (‘cost’ and ‘harm’).

Adaptive evolution in biology and technology: Why are parallels expected? by Peter Kaplan.

Integrating Knowledge From Biology Into The TRIZ Framework by Darrell Mann

and

Complexity Increases And Then. . . (Thoughts From Natural System Evolution) by Darrell Mann

Relevant links

K Niklas Evolutionary walks through a land plant morphospace Journal of Experimental Botany, Vol 50, 39-52, Copyright © 1999 by Oxford University Press

KJ Niklas Morphological Evolution Through Complex Domains of Fitness Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Vol 91, 6772-6779, Copyright © 1994 by National Academy of Sciences

Karl J. Niklas COMPUTER MODELS OF EARLY LAND PLANT EVOLUTION Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences May 2004, Vol. 32, pp. 47-66

Gabriela Ochoa On Genetic Algorithms and Lindenmayer Systems

James Watson, Janet Wiles, and Jim Hanan Towards More Relevant Evolutionary Models: Integrating an Artificial Genome with a Developmental Phenotype

Joanna L. Power A.J. Bernheim Brush Przemyslaw Prusinkiewicz David H. Salesin Interactive Arrangement of Botanical L-System Models

Integrating biomechanics into developmental plant models expressed using L-systems