Icons of ID: Circadian Rythms II

This is the second installment in my postings on Circadian Rhythms. After having introduced the IC argument for Circadian rhythms, I intend to explain in general terms how the Circadian clock works.

Let me repeat Behe’s definition of Irreducible Complexity

“By irreducibly complex I mean a single system composed of several well-matched, interacting parts that contribute to basic function, wherein the removal of any one of the parts causes the system to effectively cease functioning. An irreducibly complex system cannot be produced directly… “

Michael Behe in Darwin’s Black Box

On the Application of Irreducible Complexity by Joshua A. Smart

Knockout Experiments

The best tool thus far in determining whether a gene product is indispensable has been the knockout experiment. In a knockout experiment, mutagenesis is used to produce a null mutant, a gene that exhibits no phenotype whatsoever. The use of knockout experiments in determining an irreducible core is obvious.

Circadian clocks

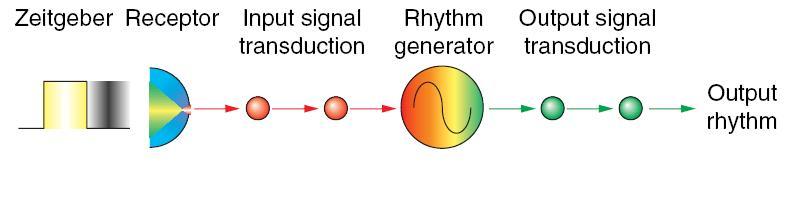

The simplest system consists of a Zeitgeber (‘time giver’) which can be light or any other external signal which drives an input pathway which drives the clock which drives the output pathway.

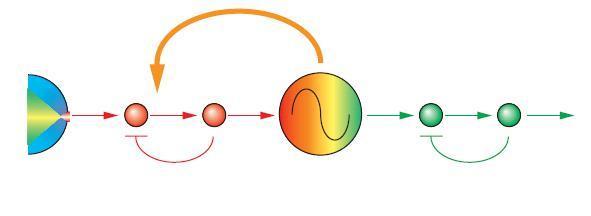

More complex systems can maintain a circadian rythm even without the external signals.

In this case the input, and output pathways form auto-regulatory feedback loops and often exhibit circadian rhythms as well. Additionally the clock protein(s) can form a feedback loop to the input pathways.

A typical Circadian clock consists of an autoregulatory negative feedback loop involving at least one gene. The gene creates an mRNA and a protein. The clock protein down regulates its own gene expression. This an initial increase in the gene expression is down regulated by the clock protein leading to an oscillatory response.

Modeling the Circadian clock

In general a feedback loop with positive or negative feedback combined with time-delays is what makes up a Circadian clock. In “Modeling Circadian Oscillations with Interlocking Positive and Negative Feedback Loops” Smolen et al test the sufficiency of the various proposed mechanisms and find that the positive feedback loop can be removed but that a time delay is essential. A time delay models processes not explicitly modelled such as transcription and translation.

Time delays are notorious in control science for adding instabilities to the system and much of the literature deals with how to ‘stabilize’ time-delayed linear systems. Time delays can lead to stable limit cycles or chaotic behavior depending on the parameter values and the exact nature of the transfer function.

Non-linear equations or linear equations with time delays are required for the system to exhibit of ‘limit cycle’ behavior.

A good example of a time delayed oscillating system involves trying to adjust the temperature of the water in the shower when there is significant delay. The unfortunate victim tries to warm up the icy cold water by adding more and more hot water, until the hot water finally reaches the shower head. The poor victim then quickly turnes down the hot water and is treated to ice cold water.

Although the simple model of positive and negative feedback and time delays can successfully model Circadian rythms, actual Circadian clocks have proven themselves to be more complicated that first thought. For instance the input pathway which transfers the signals from the Zeitgeber to the oscillatory clock is often under Circadian control as well, creating a fuzziness between input, clock and output pathways.