Shannon entropy applied

Introduction to Shannon entropy

Motivated by what I perceive to be a deep misunderstanding of the concept of entropy I have decided to take us onto a journey into the world of entropy. Recent confusions as to how to calculate entropy for mutating genes have will be addressed in some detail.

I will start with referencing Shannon’s seminal paper on entropy and slowly expand the discussion to include the formulas relevant for calculating the entropy in the genome.

But first some warnings

Okay, now that I have given these useful warnings lets have a look Shannon’s paper.

“A Mathematical Theory of Communication”, Reprinted with corrections from The Bell System Technical Journal, Vol. 27, pp. 379-423, 623-656, July, October, 1948. By C. E. SHANNON

Suppose we have a set of \(n\) possible events with probability \((p_1,...p_n)\) the entropy for such a situation is defined by:

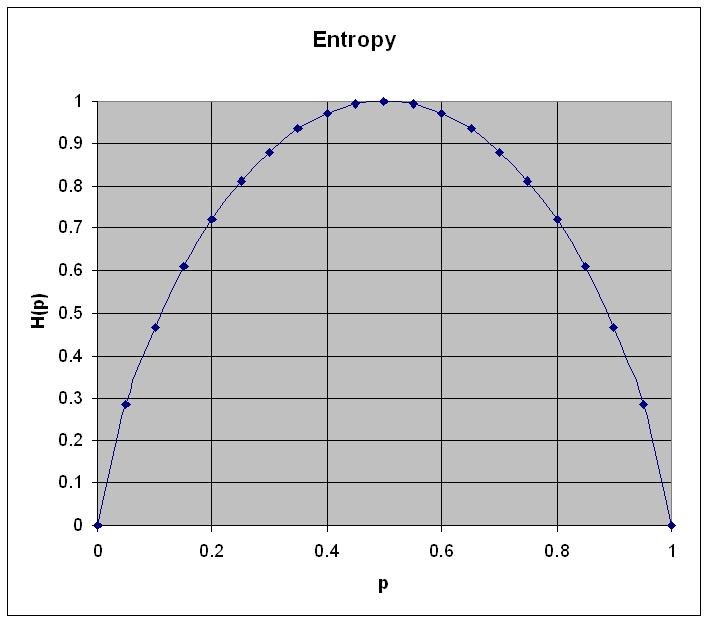

\[H = - \sum_{i} p_i \log(p_i)\]I will apply this formula to a simplified example in which there are two events with probability p and q where q=(1-p) since the sum of the probabilities adds up to 1. Theh entropy in the case of two possibilities with probabilities p and q = 1 is given by:

\[H(p) = -(p \log p + (1-p) \log (1-p))\]

Figure 1: Entropy for a system with two states. The horizontal axis describes the probability p and the vertical axis the entropy \(H(p)\) as calculated using the formula above

Some important observations:

- Entropy is zero when probability for p=0 or p=1

- Entropy is maximum when p=q=0.5

Observation 1 can be expressed more generally by observing that if the probability for any one of the variables is 1 that the entropy is minimal.

Observation 2 can be made more universal by observing that the entropy for n variables is maximum when \(p_i=1/n\) or in other words, a uniform distribution.

Extending Shannon entropy to the genome

Various people have taken the work by Shannon and applied it, quite succesfully, to the genome.

Tom Schneider’s website contains a paper called evolution of biological information which shows how to apply Shannon entropy to entropy calculcations for the genome. In addition Schneider provides us with a more in-depth introduction into Information theory.

For those interested in how to correctly apply entropy calculations to the genome, I refer to the excellent introduction by Tom Schneider.

Schneider has succesfully applied Shannon entropy to identify and predict binding sites

Some successes include:

N. D. Herman and T. D. Schneider, High Information Conservation Implies that at Least Three Proteins Bind Independently to F Plasmid incD Repeats, J. Bact., 174, 3558-3560, 1992.

T. D. Schneider and G. D. Stormo, Excess Information at Bacteriophage T7 Genomic Promoters Detected by a Random Cloning Technique, Nucl. Acids Res., 17, 659-674, 1989.

Schneider’s 1997 paper Information content of individual genetic sequences published in J. Theor. Biol. 189(4): 427-441, 1997 shows an example of application of Shannon entropy.

Now we can extend this using Adami’s 2002 paper Adami C. (2002) “What is complexity?”, BioEssays 24, 1085-1094.

The entropy of an ensemble of sequences X, in which sequences \(s_i\) occur with probabilities \(p_i\) is calculated as

\[H(X) = - \sum_{i=1} p_i \log p_i\]where the sum goes over all different genotypes i in X. By setting the base of the logarithm to the size of the monomer alphabet, the maximal entropy (in the absence of selection) is given by \(H_{max}(X) = L\) , and in fact corresponds to the maximal information that can potentially be stored in a sequence of length L. The amount of information a population X stores about the environment E is now given by:

\[I(X:E)= H_{max} - H(X|E) = L + \sum_{i=1} p_i \log p_i\]The entropy of an ensemble of sequences is estimated by summing up the entropy at every site along the sequence. The per-site entropy is given by:

\[H(j) = - \sum_{i=(A,C,T,G)} p_i(j) \log p_i(j)\]for site j, where \(p_i(j)\) denotes the probability to find nucleotides i at position j. The entropy is now approximated by the sum of per-site entropies:

\[H(X) = \sum_{j} H(j)\]so that an approximation for the physical complexity of a population of sequences with length L is obtained by

\[C(X) = L - H(X)\]

Adapted from: Does complexity always increase during major evolutionary transitions?

From this it should be obvious that \(H(j)\) is zero when a particular mutation becomes fixated in the genome since one of the probabilities will be 1 and the others zero.

For those who wonder: \(\lim \limits_{p \to 0} p \log p = 0\)

Schneider has some interesting results which show what happens to the entropy in the genome with and No selection. It should be obious that, not surprisingly, the information remains constant around zero.

Figure 2 (from Schneider’s talk): Notice how the information in the genome increases under selection but disappears once selective constraints are removed. Once selection is added, the information quickly approaches the theoretical values

From Jerry’s to Shannon

Jerry’s entropy \(S = \log W\) using the following transformations

For the human genome we look at a particular location and observe over many samples and we find \(N_A\), \(N_C\), \(N_T\) and \(N_G\), we calculate the total number of states to be:

\[W = \frac{(N_A+N_C+N_T+N_G)!}{N_A!N_C!N_G!N_T!}\]using Stirling’s approximation \(\log M! = M(\log M -1)\) we find

\[W = -N (p_A \log p_A + p_C \log p_C + p_G \log p_G + p_T \log p_T)\]where

\[p_A = \frac{N_A}{N_A+N_C+N_T+N_G}\]and

\[p_C = \frac{N_C}{N_A+N_C+N_T+N_G}\]and

\[p_T = \frac{N_T}{N_A+N_C+N_T+N_G}\]and

\[p_G = \frac{N_G}{N_A+N_C+N_T+N_G}\]Remember that entropy is a statistical property. See also this paper

Some relevant papers

“Significantly Lower Entropy Estimates for Natural DNA Sequences”, David Loewenstern, Journal of Computational Biology (under revision)

Abstract wrote:

Abstract: If DNA were a random string over its alphabet {A,C,G,T}, an optimal code would assign 2 bits to each nucleotide. We imagine DNA to be a highly ordered, purposeful molecule, and might therefore reasonably expect statistical models of its string representation to produce much lower entropy estimates. Surprisingly this has not been the case for many natural DNA sequences, including portions of the human genome. We introduce a new statistical model (compression algorithm), the strongest reported to date, for naturally occurring DNA sequences. Conventional techniques code a nucleotide using only slightly fewer bits (1.90) than one obtains by relying only on the frequency statistics of individual nucleotides (1.95). Our method in some cases increases this gap by more than five-fold (1.66) and may lead to better performance in microbiological pattern recognition applications.

One of our main contributions, and the principle source of these improvements, is the formal inclusion of inexact match information in the model. The existence of matches at various distances forms a panel of experts which are then combined into a single prediction. The structure of this combination is novel and its parameters are learned using Expectation Maximization (EM).

Experiments are reported using a wide variety of DNA sequences andcompared whenever possible with earlier work. Four reasonable notions for the string distance function used to identify near matches, are implemented and experimentally compared.

We also report lower entropy estimates for coding regions extracted from a large collection of non-redundant human genes. The conventional estimate is 1.92 bits. Our model produces only slightly better results (1.91 bits) when considering nucleotides, but achieves 1.84-1.87 bits when the prediction problem is divided into two stages: i) predict the next amino acid based on inexact polypeptide matches, and ii) predict the particular codon. Our results suggest that matches at the amino acid level play some role, but a small one, in determining the statistical structure of non-redundant coding sequences.

Entropy in biological sciences

Adaptation and organism complexity (Chris Adami)

Using Molecular Evolution and Information Theory to Improve Drug